Is the UN needed for peace in Ukraine?

In Terris 25.01.2023 mons. Michele Pennisi Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgIn these days when the winds of war are blowing in Ukraine and in other parts of the world with the risk of a new world conflict, as dreaded by Pope Francis who has made humanity's cry for peace heard, it is important to ask ourselves about the role of the international community and about a world authority that can authoritatively intervene to guarantee peace. Christian thinkers, starting from ‘Pacem in Terris’ have reflected on the theme, among them Don Luigi Sturzo.

Don Luigi Sturzo's ideas on peace and war were and still are too innovative and distant from contemporary political thought and from the classical elaboration of Christian thought itself on the just war. This requires the revisiting of the concept of national sovereignty and the creation of multilateral institutions, which would set more appropriate rules not only in the economic and financial field, but also in the political and military spheres. The reflections elaborated by Father Luigi Sturzo, especially between World War I and World War II, on the issues of peace, the international community and overcoming the right to war, constitute an original and topical contribution to the construction of a new civilisation based on moral values aiming to the creation of an international and supranational authority capable of affirming law over force and guaranteeing a just peace among nations.

His strong moral demand is combined within an irreplaceable historical-political dimension that restores concreteness to the utopia of peace. Sturzo's thought on peace and war is articulate and dynamic and over the course of half a century undergoes transformations and developments, responses that are increasingly more appropriate to historical reality, passing from the theory of the 'just war' to the idea of the ‘uselessness of war’, due to its multiplied capacity for destruction, and to the ‘inevitability of peace’.

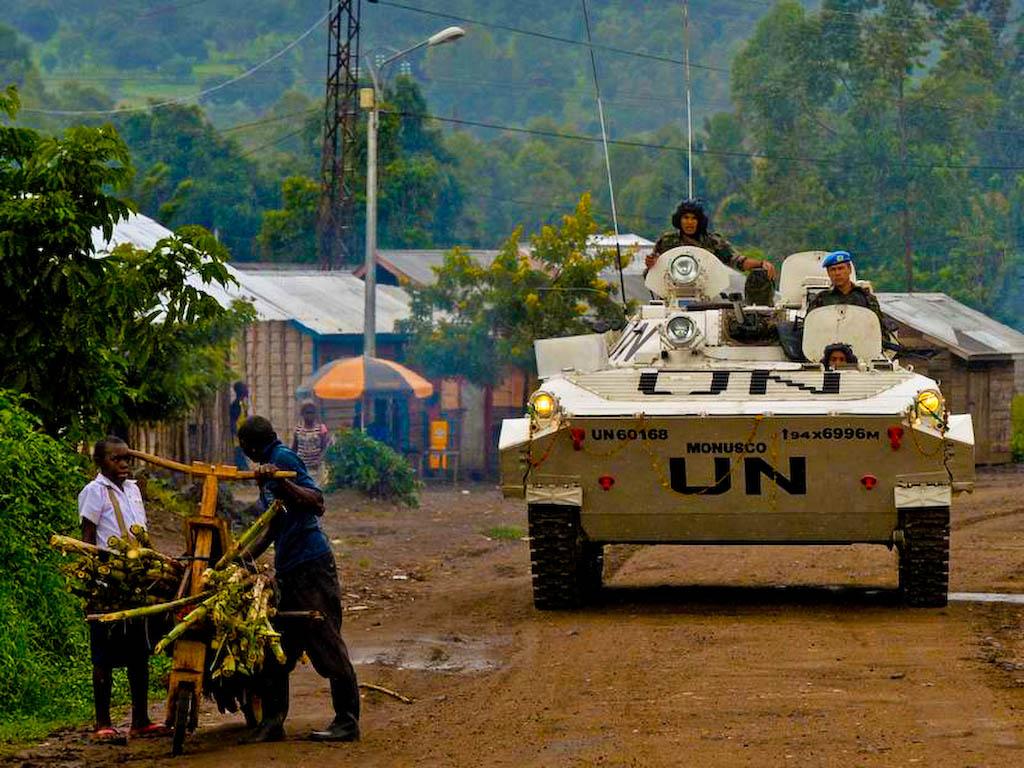

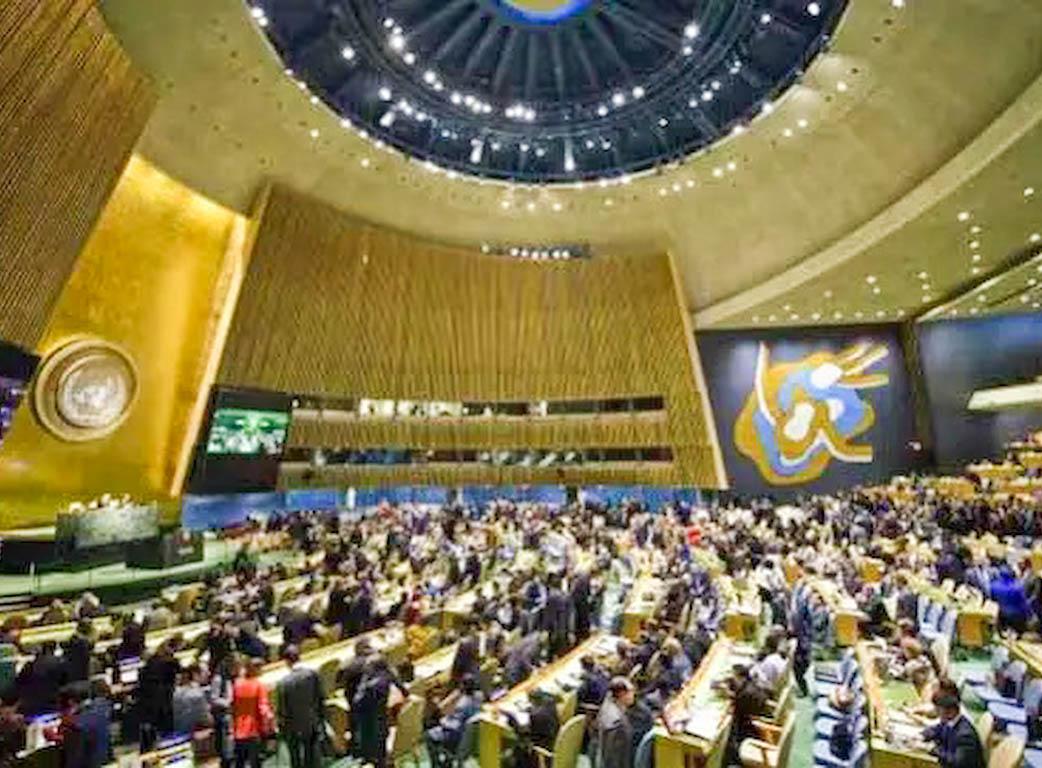

Sturzi's arguments regarding the overcoming of the concept of a 'just war' and the political commitment to peace can be summarised in a few points: politics is only good when it is 'righteous', i.e. it refers to moral values and first of all to respect for the human person; nations must, in some cases, be subjected to precise political limits by an international organisation with universally recognised moral authority. Sturzo identifies the main instrument of an international organisation with a universal character: the League of Nations in 1919 and in 1945 the United Nations (UN) aimed at eliminating war, but he also identifies the limits of these organisations.

After the Second World War, the utopian hope of developing a world government that would guarantee peace between states was nurtured. Among Catholics it is enough to mention Florence’s Giorgio la Pira and among laymen Aldo Capitini and Norberto Bobbio. The need to achieve the constitution of a world 'authority' capable of building a community of nations has been addressed by the social magisterium of the Church, starting with John XXIII's 'Pacem in Terris', the 60th anniversary of which is now being celebrated.

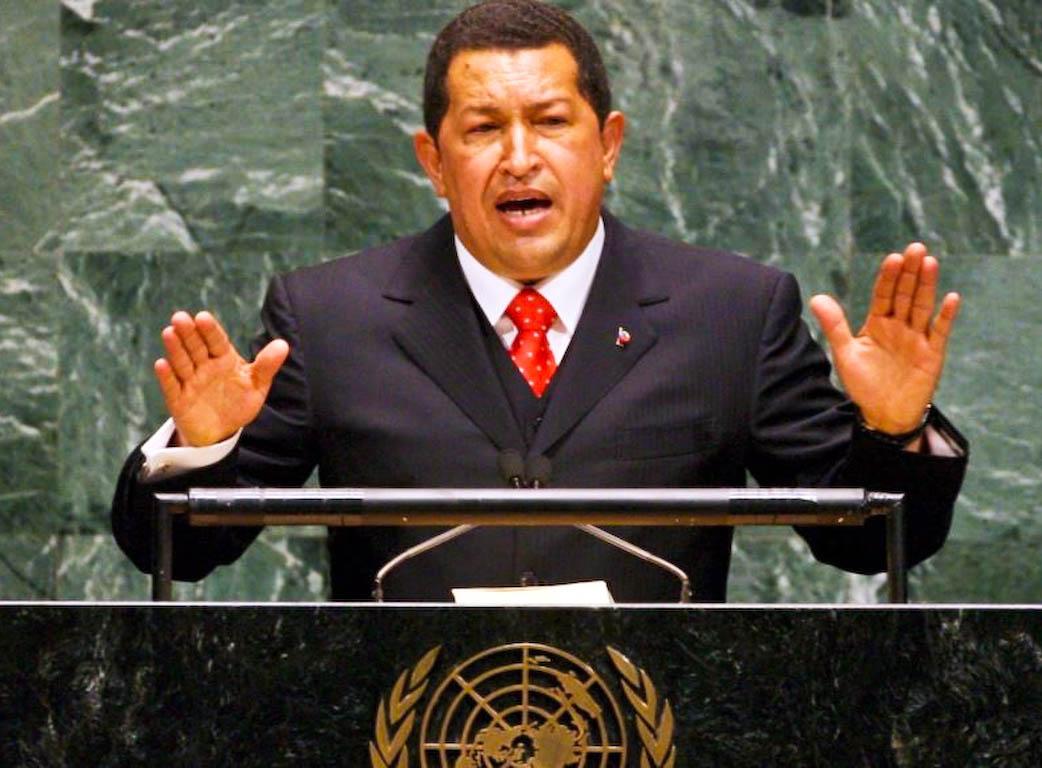

Note. To this reflection must be added the criticism that comes from too many sources about the inefficiency, bureaucratisation and ideologisation of an institution that over the decades has left ideals by the wayside to listen too much to lobbying and heads of state who only serve their own interests. That is why we have added the question mark to the original title.

See, Per la pace in Ucraina serve l’Onu

Photo. The heavily shelled town of Lisichansk in rebel-held eastern Ukraine © Brendan Hoffman/Mercy Corps

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment