The Christmas star

Racconti e leggende 24.12.2024 Paul Roland Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgOf all the miners in Griqualand (South Africa), Pierre Valaur was the only one who was not celebrating joyously on the evening of 24th December 1875. Outside the camp, the Kaffirs - from the Arabic word kaffir (infidel), a derogatory name given by the Arabs to Africans - had lit large fires around which the miners were dancing to the sounds of a fanciful orchestra. In the room of the only inn, lit for the occasion by huge paper lanterns hung from a gigantic Christmas tree, the diamond diggers were making a lot of noise.

In his miserable hut, Pierre was spending the saddest Christmas Eve he had ever known. An orphaned Frenchman who had one day found himself heir to ten thousand francs left by a distant relative, he had let himself be lured to this corner of Africa where the discovery of diamond mines had caused quite a stir.

Pierre was twenty-seven years old and full of energy: he had resolved to use his modest nest egg to buy a slice of this diamond land, where a Boer farmer called O'Reilly had first found one of these precious stones, sold for the fantastic price of one million three hundred and seventy-five thousand francs.

‘Who knows,’ he said to himself, ‘if I don't have the same luck!’

He set off. After paying for his trip, he had just enough money left over to buy a very small plot of land and the equipment he needed to operate it. Full of hope, he set to work; sober, tenacious, hard-working, he should have succeeded, if, in these kinds of adventures, chance didn't play such a big part! And, alas! After three years of constant toil, Pierre found himself poorer than when he had arrived. While many of his companions were getting richer, he was only able to get from his land diamonds of minute weight, the sale of which barely enabled him to live in this new country where basic necessities were of enormous price.

Four times he changed the ground, hoping that elsewhere the land would be more productive: bad luck followed him. Then he weakened, gave into despair, no longer wishing to vegetate in this ungrateful Griqualand, nor to return to France where no beloved face would smile at him. That Christmas night, remembering the sweet joys of his childhood, while his companions indulged in pleasure, Pierre succumbed to cowardice: he resolved to kill himself, to leave this life where nothing holds him no more.

He went out. The night was clear and warm, one of those beautiful African summer nights when thousands of stars twinkle. He walked past a line of silent huts, deserted by the miners who were singing Christmas carols in the inn. Pierre hurried towards the land of diamonds, where, to brave the fate that had defeated him, he wanted to throw himself from the top of his mine, thirty metres deep.

As he reached the last hut, a pretty child's voice stopped him. Instinctively, he let himself be distracted from his fatal goal, skirted around a small clump of eucalyptus trees that shaded the dwelling, and reached a corner of overgrown land in the middle of which he saw a small creature, hands clasped, head held high.

‘Good Father Christmas’, she was praying, ‘put that beautiful star I see up there in my shoe tonight, and I'll play with it every day.’

When she heard the noise, the little girl got up. Without being frightened, she smiled at the miner who asked her: ‘Who are you?’

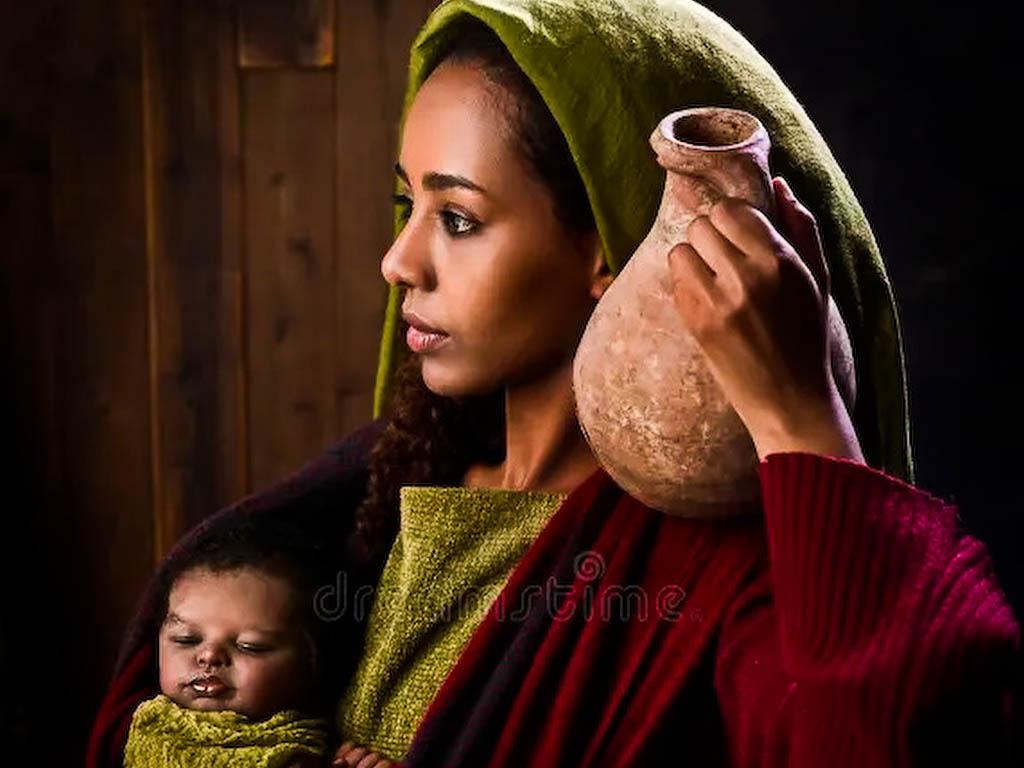

‘Laetitia Vasari, I'm five years old and I'm waiting for Daddy.’ Pierre held back an exclamation. That very morning, Andrea Vasari had been killed by his companions for stealing; no one had given a thought to the orphan girl, who held such a tiny place in this somewhat wild camp that she had been living in for two years – living at her ease no longer having a mother. After his wife's death, Vasari, who was a thief by profession, had come to Griqualand to escape the police’s close surveillance, in the hope of amassing the fortune his deplorable conduct had not brought him. Unwilling to part from his beloved daughter, he took her with him, and thanks to his father's solicitude, Laetitia never had to suffer during her stay in the camp.

But what was to become of her now that her father was dead, a victim of his incurable penchant for thievery! Pierre looked at the orphaned girl pensively. Seeing that she was shivering and that her face was pale, he didn't want to worry her and tried to smile at her while shaking her hand.

‘What were you asking Santa for?’

‘A star.’

‘A star!’, he repeated in surprise, ‘What for?’

‘To play with. Oh, I won't break it, and when it's dark in our house, it'll give me light. Up there, can you see it on the tip of my finger? It's the most beautiful!’

The young man took the little girl in his arms, led her into the house and laid her down in her bed, which her father's hand had not made any better in the morning. Docile, she drank the hot tea he had prepared for her, thanked him and asked him to fetch ‘her darling daddy’ as soon as possible.

He said goodbye and was about to leave, when, noticing the shoe standing prominently on the doorstep where Father Christmas was to enter - the house had no chimney - he explained, to prepare her for the deception at her waking up:

‘Don't count on your star, the sky is too high for old Santa to climb up there and pick it up.’

‘Do you think so?’, she replied, smiling. ‘He'll take a ladder, I begged him so much.’

Without the courage to destroy the confidence of the child, who didn't know that a star is not a bright, shining diamond that Father Christmas can bring in as a gift, but an immense and distant world, he left her and resumed his hasty march towards death.

The field of diamonds was not dark, for the night was superb. Without hesitation, without regret, he walked briskly to his estate, which, like the others, was enclosed by a fence of wooden posts. He stopped at the very edge, crossed his arms and thought coldly: ‘My life is of no use to anyone, so it belongs to me. No one will suffer of my death,’ he added, thinking of Vasari who had left his daughter alone in the world.

The sad condition of this child, whom only yesterday he had barely known, suddenly tore him away from his own anguish. His heart tightened, frightened by the suffering that the future holds in store for Laetitia. The little voice chirped in her ear: ‘He'll get a ladder; I've begged him so much!’

He looked up at the sky. Oh, how the star the little girl had shown him was sparkling! He didn't dream for long; with a sudden gesture he threw himself backwards, away from the well where he wanted to throw himself. ‘Just a few more hours for her,’ he said to himself resolutely. ‘She prayed so well. If only I could put a star in her shoe!’

He went to Vasari's hut, listened at the door for the orphan's slightly hasty breath, and returned to his dwelling. The miners were still singing, the fires blazing through the branches. The young man entered his deserted hut, lit a lantern, took a heavy bundle of cables, his pickaxe and two leather buckets, returned to the diamond field and descended with the help of ropes to the bottom of his mine, where death had been waiting for him just a moment before.

When his two buckets were full of earth, he tied them to the ropes, climbed back up, hoisted the buckets up, and returned home to sift, by the light of his lantern alone, the cursed earth that was always deceiving his hopes.

****

‘Here, Valaur! There's Pierre. What's happened to him? Have you finally had a bit more luck? Come and sing and drink with us; you're too sober, fortune only smiles on those who drink.’

These words, prompted by his sudden appearance, were echoed in the room where the miners were having the Christmas picnic. Pierre's face did not relax, his lips remained closed.

‘It would seem,’ said a snide voice, ‘that Valaur has just found a fortune.’

‘That’s precisely,’ Pierre's voice said softly. He was pale and agitated. They all got up at once, approaching him and speaking together: ‘Where? When? How big is it? How many carats?’

The young man pulled a shiny stone from his pocket, larger than a large hazelnut. A tremendous cry of enthusiasm escaped from all the chests. The diamond weighed at least a hundred carats (twenty grams). It was worth more than half a million.

Christmas, wine and pipes were forgotten; the lucky owner of the treasure was besieged with questions; hope lit up the eyes around him: today it was the Frenchman, tomorrow it would undoubtedly be someone else this land would enrich that had been so thoroughly excavated by pickaxes.

Deaf to these pressing questions, Valaur was talking to Cornelius, the Dutchman, who worked at Griqualand as a lapidary, a diamond cutter. He was listening to the young man's explanations, caressing with his finger and his gaze the shapeless stone he would soon be cutting. Pierre told the story in a few words. Having found André Vasari's daughter alone and feverish, he had wanted to try his luck for her, and in the two buckets of earth brought in from the field, he had found this diamond, a Christmas gift for the orphan.

A few hours later, the young man left the lapidary's, clutching in his hand a cut diamond of lesser value than his own, lent to him at his request by Cornelius, who had kept the other as a pledge. For the rest of the night, sitting on the threshold of Laetitia's half-open door, he rubbed the diamond with a woollen cloth, and when the little girl woke up in the morning, he hastily placed the shiny jewel on the tip of the little shoe that was waiting for Father Christmas to come and visit.

His heart pounding, he watched. A cry of rapt ecstasy came from the bunk: ‘My star!’ In two leaps, Laetitia was at the shoe; kneeling down to take in her little hand the stone that sparkled with all its facets, she placed a kiss on it, then said gently: ‘You made a mistake, Santa, the other one was bigger, but it doesn't matter, this one shines just as brightly.’

Through the windows, Laetitia caught sight of Pierre and beckoned him in: ‘You see, he took a ladder to pick down my star from Heaven.’

He kissed that clear, joyful child's face, whose memory there by the mine had snatched him from death, and the beautiful, clear blue eyes seemed to him more precious than the biggest diamonds in the world. He told himself that soon she would ask for her father, that he would console her, cradle her, call her his daughter, and life would seem good to them both; she was so little and forgetting is so easy at that age.

The Christmas Star had saved a man and given the child a father.

See, L'étoile de Noël

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment