What role do women play in peace processes in the Great Lakes region?

www.justicepaix.be 05.06.2023 Keren Tchatat Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgThe lack of women’s representation in peace processes is an obstacle to conflict resolution and the establishment of lasting peace in the Great Lakes region. It is therefore important to focus on the integration of women at the highest levels of decision-making.

The participation of women in peace processes worldwide remains lower than that of men, although it is slowly changing. According to UN Women, between 1992 and 2019, women accounted for an average of 13% of negotiators and 6% of signatories in the world's main peace processes. In other words, 7 out of 10 peace processes did not include any female mediators or signatories.

Not only do these processes exclude women from decision-making, they also neglect the inclusion of women in strategies that could reduce conflict and advance stability.

Focusing on the inclusion of women in formal peace processes highlights the fact that women's participation in conflict prevention and resolution can have a positive impact before, during and after conflicts.

It also notes that more recent peace efforts have difficult to include women. In particular, women were largely excluded from peace negotiations during the war in Ukraine. In terms of official roles in discussions relating to this war, there were only two women: Iryna Gerashchenko and Olga Ajvazovska. They were part of the Ukrainian delegation at the peace talks. On the Russian side, there were no women present.

This lack of women’s representation in the peace process remains an international problem. It was against this backdrop that the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security on 31 October 2000. With this resolution, the UN requires its Member States to systematically take into account the interests of women in peacekeeping and peacebuilding activities. It recognises that sustainable peace cannot be achieved without the full and equal inclusion of women.

The resolution has several key points, including increasing the number of women at all levels of decision-making. It also calls for more women to be involved in peace negotiations and agreements within national and international institutions and mechanisms. In line with this, the resolution also calls for the appointment of more women envoys and special representatives of the UN Secretary-General.

As researcher and author Chineze J. Onyejekwe explained at a special session in 2002: "The Security Council encouraged greater consideration of the gender perspective integration into conflict resolution and reconstruction."

The UN Security Council thus recommends that political actors take various measures to encourage the participation and protection of women, and thus ensure conflict prevention and the promotion of peace. This would be done in the fairness interests, because there are as many women as men in the world. Moreover, women make up half of the populations affected by conflicts.

Lack of representation of women when signing peace agreements in the Great Lakes region

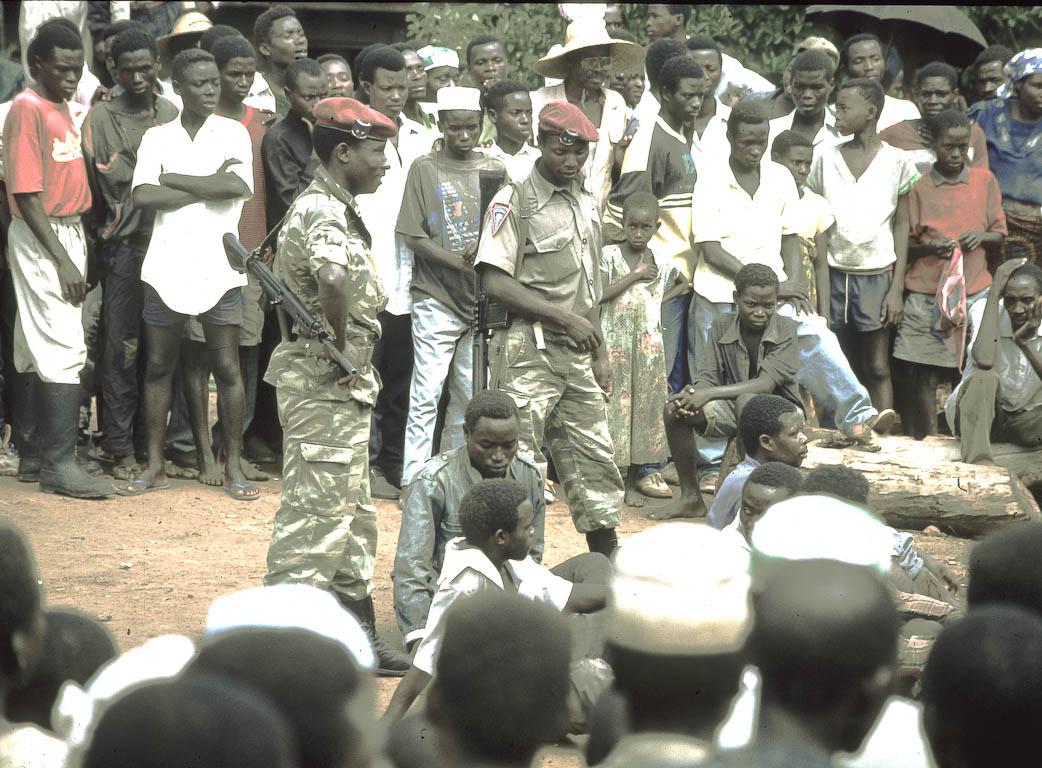

In Central Africa, particularly in the Great Lakes region, women are the most marginalised victims of armed conflict. In particular, they suffer rape and sexual violence. During and after conflicts, they often find themselves widowed and, as a result, at the head of households.

This could mean that they are not expected to play a part in the search for peace. As Marguerite Mutuminka, President of COCAFEM - Concertation des Collectifs des Associations Féminines de la Région des Grands Lacs, set up in 2001 by Burundi, DR Congo and Rwanda - explains, "Our culture privileges men more than women. Her voice is muzzled. And this is an ongoing struggle to ensure that women can speak out and provide solutions in times of war or dispute."

In Rwanda, for example, after the 1994 genocide, women's organisations were the first to initiate dialogue in various communities. Meanwhile, in Burundi, at the start of the negotiations in Arusha in 1996, there were only 2 women out of 126 participants.

They demanded and obtained an increase in female representation. In the 1980s, in Bukavu in DR Congo, women demanded to be included in the process of negotiating peace and rebuilding the country. In response, governments tried to take greater account of gender in their governance policies (Tukumbi Lumumba-Kasongo - 2017. Paix, sécurité et reconstruction post-conflit dans la région des Grands Lacs d’Afrique, p. 22).

Women must be involved in decision-making and negotiations at the highest levels if they are to have a significant impact. The appointment in 2013 of Mary Robinson (former President of the Republic of Ireland) as the United Nations Special Envoy for the Great Lakes Region is a case in point. This appointment raised hopes of a greater role for women at the highest decision-making level in peace processes. One of her mandate objectives was to emphasise the crucial role of women in building lasting peace. According to Ms Robinson, no society can make as much social, economic and political progress if part of its population is marginalised (Reilly, N. & Warren, R. - 2014. Le Leadership et la participation des femmes, p. 6).

With this in mind, in 2014 she took the initiative in setting up the Plateforme des femmes pour l’Accord-cadre pour la paix, la sécurité et la coopération pour la RDC et la région (ACPSC) (Women's Platform for the Framework Agreement on Peace, Security and Cooperation for DR Congo and the Region). This initiative was set up to meet the need for facilitation and coordination in the contribution of women's organisations to the implementation of the Framework Agreement.

The Framework Agreement (ACPSC)

It is necessary to dwell on the ACPSC because it is a major agreement in the establishment of peace in the Great Lakes region in general. The main objective of this agreement is to advance the peace and reconciliation process. The Framework Agreement has been ratified by eleven countries in the region, and by four international organisations. It is interesting here to analyse the place of women in the ACPSC and the negotiations that led to its signature, as well as the effectiveness of their participation in the peace process.

It can be seen that women in DR Congo are still particularly excluded from political decision-making processes and from efforts relating to the peace process in the Great Lakes region.

This could be explained firstly by the persistence of socio-cultural norms which attribute to men a position of authority at home. In addition, insecurity and instability increase gender inequalities.

The process that led to the signing of the Framework Agreement effectively sidelined Congolese women and women in the region as a whole. If we look at the number of women present at the Framework Agreement signing, we see that of the 11 signatories, all were men. What's more, of the 4 witnesses present, only one was a woman (Nkosana Dlamini Zuma, Chairperson of the African Union Commission). Yet women, just like men, should be present at all levels of decision-making in peace processes.

More often than not, in peace talks, women usually play a simple advisory or observation role, particularly through civil society organisations. Women are rarely given decision-making positions, which means that their opinions and proposals are invisible. These are generally not taken into account at the signing stage either.

In light of this observation about the low level of representation of women in peace negotiation processes, we need to look at ways of including women.

Ways of including women in peace negotiations in the region

It is clear from this analysis that taking women's participation into account is an important element in any peace process.

Given the importance of resolving the conflicts in the Great Lakes region in a sustainable manner, it is essential to broaden the concept of gender in peace-building.

This could be done first of all at national and even regional level, by integrating women at the highest level of institutions, in positions of responsibility. It is therefore not enough to reserve only gender or children's issues for them.

Women should not just be in positions where they are mere witnesses or observers. They must be protagonists in the discussions and signatures of peace. This would be illustrated by the same reasoning behind the appointment of Bineta Diop as the African Union's special envoy for women, peace and security. This is indeed a step forward.

It would also be necessary to establish a more effective platform for women to implement and monitor regional agreements. This could take the form of an advisory committee, through organisations such as the aforementioned COCAFEM. It could also be important to recognise informal mediation efforts at local level as an integral part of peace processes. Indeed, women play a daily role in the Great Lakes region.

However, the inclusion of women in negotiations and peace processes in the region must also be supported at an international level. This can be achieved by encouraging compliance with international standards on issues relating to women, peace and security. In particular, the UN Security Council could ensure that Resolution 1325 is properly implemented by national governments. The latter could be obliged to provide national plans of actions indicating precisely the measures that these governments are putting in place to ensure compliance with the Resolution's obligations. National associations could also support local women's civil society organisations, so that they can have a major impact on decision-making.

See, Quels rôles jouent les femmes dans les processus de paix de la région des Grands Lacs ?

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment