The war in Ukraine's impact on the synodal process

Stati Uniti 12.04.2022 Massimo Faggioli Translated by: Jpic-jp.org“Putin's attack on a sovereign country helps us realize what we can and cannot expect in terms of participation in the synodal process of Catholics in Ukraine, but also of those in other war-torn areas around the world. They cannot offer a well-crafted synthesis of listening sessions. Their contribution will be of another kind: less quantifiable, more mystical. Their suffering can teach a great lesson about what it means to be Church in today's world. Synodality also means that we Catholics must discover how we can ‘walk together’ with the suffering Churches at this time”. Really, major ecclesial events have always been influenced and shaped in some way by the social, cultural and political climate of the time.

The first casualty of war is the truth, and the war in Ukraine has created a mindset that will inevitably have an impact on the “synodal process” that is taking place in the Catholic Church.

Meeting, listening and discerning are much more difficult in times of war – and at the same time more urgent.

Even before the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24, the synodal process was presenting the Church with unusual problems.

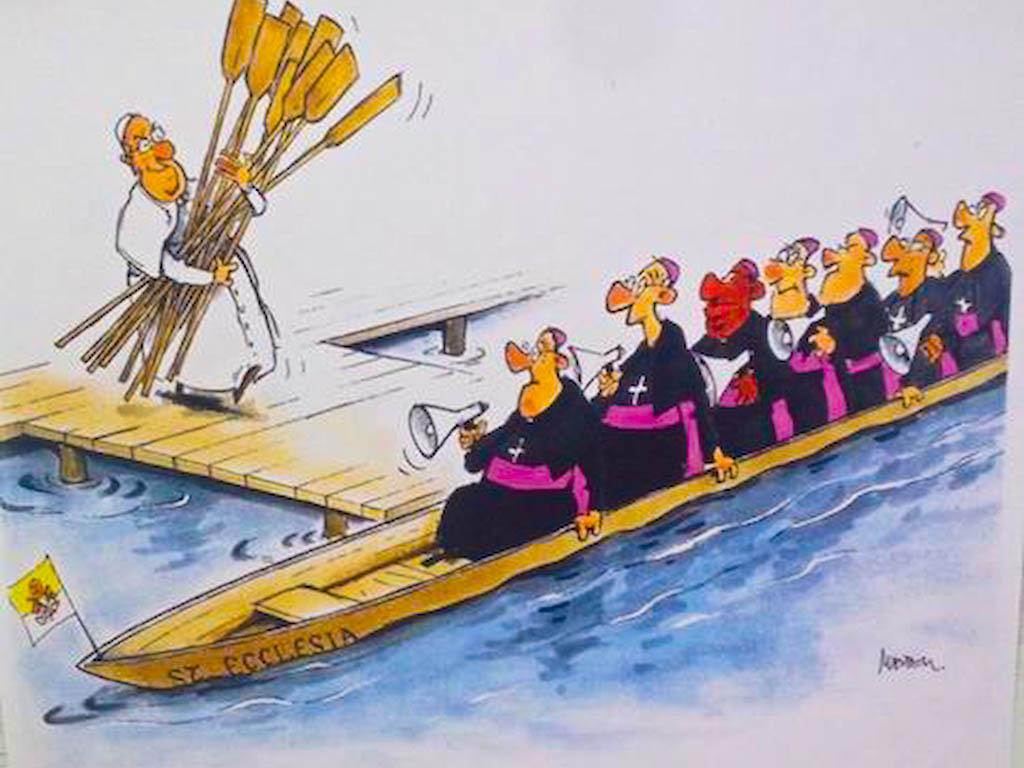

For instance, the Synodal Path that's taking place in Germany has been attacked in the past several months by various bishops from other parts of the world – individuals like Archbishop Samuel Aquila of Denver (USA) and entire bishops' conferences in countries like Scandinavia and Poland.

And just this week, some 74 bishops from around the world - including 49 from the United States - signed a "fraternal open letter", telling the Germans their Synodal Path is causing confusion and could lead to schism.

The war in Ukraine has dramatically changed the mood in the Church also from the point of view of the international political context. The conciliar and synodal gatherings in the Catholic Church have always interacted with armed conflicts. Their agendas and schedules were not immune from the effects of turmoil in the international order.

Church gathering shaped by events of the time.

It is enough to look at the last couple of centuries. The First Vatican Council I (1869-1870) was suspended, effectively interrupted, by the war that led to the capture of Rome by the Italian kingdom in September 1870. Worries about security, both domestically and internationally, deterred Pius XI and Pius XII from re-convening a general council in the 1920s and immediately after World War II.

Vatican II (1962-65) would have been interrupted if the October 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis had escalated to a nuclear confrontation between the two superpowers, the US and the USSR.

General or ecumenical councils are not like synods at the diocesan and national level, and there are some precedents here. For example, the synodal movement at the end of the 18th Century was interrupted by the French Revolution.

After the fall of Napoleon, the pre-existing political order and a consolidation of papal power were restored. One of the many paradoxes of the anti-clerical attacks between the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th centuries is that it made the Catholic Church more papal and less synodal, as the definitions of Vatican I made clear.

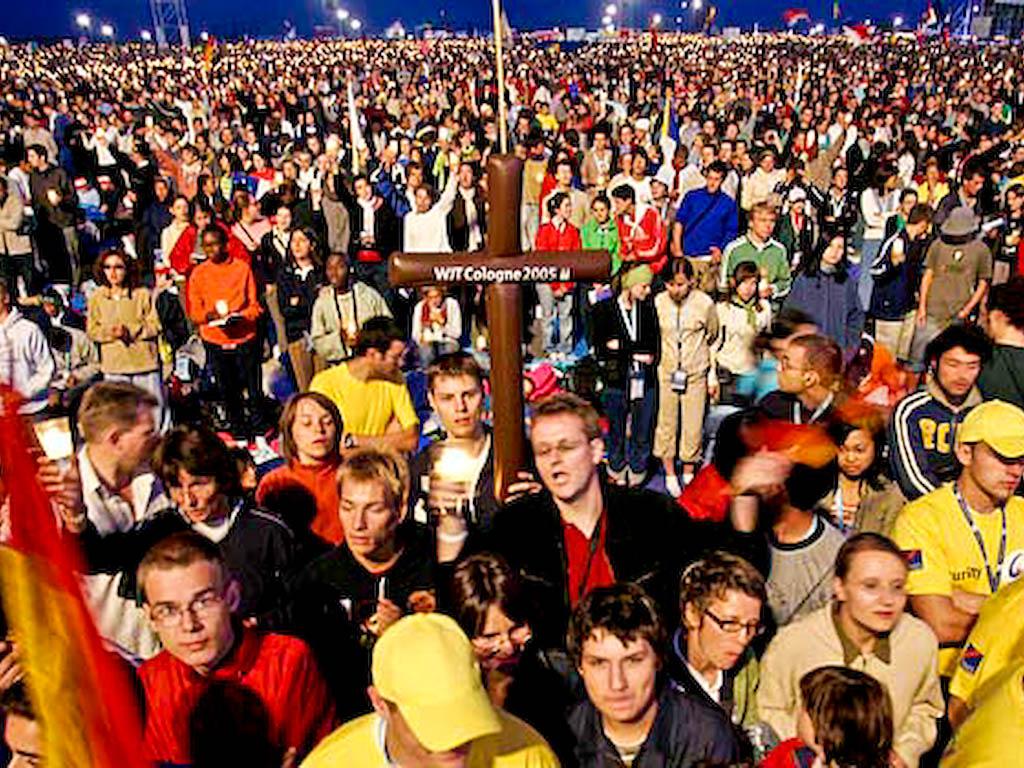

The 2021-2023 synodal process has opened the Church up to one of its most historically important experiences of encounter with its members at the local, national, and global levels. But, it comes at a time when fears of a nuclear war are at their highest since the Cuban missile crisis sixty years ago.

Clashes and confrontations

The novelty is that the future of what seemed to be an island of peace in a troubled world - that is, Europe -, seems as uncertain as it has been at the approach of World War II. In an interesting article published in Bloomberg recently, John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge (two journalists with a keen eye for the relations between religion and politics) wrote the following. “In the great intellectual battle of the 1990s between Francis Fukuyama, who wrote The End of History and the Last Man (1992), and his Harvard teacher Samuel Huntington, who wrote The Clash of Civilizations (1996), CEOs have generally sided with Fukuyama.”

The view from the boardroom has been straightforward: Democracy would not always win (China taught capitalists that quickly), but sensible economics usually will. However, at the end of the paragraph, Micklethwait and Wooldridge came to this conclusion: While "Capitalists are all Huntingtonians now," the modern, post-conciliar papacy is by default embodying a vision that is not Huntington's "clash of civilizations".

But, the turn to a confrontational view of the relations between peoples and cultures is not leaving Catholics miraculously unaffected.

The American "culture wars"

In the hearts of many local Catholics, who now are supposed to "walk together" with their brothers and sisters in the faith and in the one human family, there is fear. What they hear in their churches is sometimes in contrast, sometimes in unison with the drumbeats of war. Synodality was supposed to be an antidote to the creation of entrenched positions in the Church, the inability to dialogue and work together. But, there is currently an escalation in the globalization of the globalization of American “culture wars”.

We have seen symptoms of this in the last few weeks. In addition to the unprecedented opposition Pope Francis has long been facing from neo-traditionalists, the war in Ukraine has created other voices of opposition to him because of his decision not to publicly cast Putin and Russia as any more of a religious enemy than they are already perceived. The criticisms are not coming from the usual cabal of US traditionalists and their international franchises, but in a more subtle way from other circles, even in Europe. During a war, the liberal democratic order is temporarily suspended and extraordinary measures are passed that significantly extend state powers and limit the population's rights.

The social, cultural and political climate of the time

The Catholic Church is not a liberal democracy, and synodality is not supposed to turn the ecclesial system in a democracy.

But there are similarities between the effects of war on democracy and on synodality in the Church, between the crisis of democratic ethos and also of synodal ethos. The focus is more on strong leadership than on the people's agency and responsibility. Propaganda replaces truth. The "other" is subject to a process of construction of the image of the enemy.

Synodality is supposed to make the Catholic Church more dialogical internally and with other Churches. But at both the local and international levels, ecumenical relations with the Orthodox Churches (and within Orthodoxy itself) are now at their lowest level in a long time. From an historical point of view, scholars of councils and synods know that such ecclesial events can only be understood by including the social, cultural and political climate of the time. We are also learning how to include the voices of those who could not be there in person or as key characters of the event (for example, women at Vatican II). We need to do that now and over the next few years for the "synodal process".

What can Catholics in war situations contribute to the synodal process?

In one sense, there will be many missing voices from the synodal process of 2021-2023 also because of war, but they still need to be listened to. In another sense, the synodal process is the continuation of the ecclesiology of Vatican II. But this moment also marks the end of the age of Vatican II, of that post-WW2 worldview looking forward to the end of the Cold War.

From a theological point of view, it is true that synodality is not a new concept but finds its deepest roots in the ancient tradition of the Church. But we must remember that synodality today is unfolding in a Catholic Church that is more global, less identifiable with one particular area of the world that dominates the others ecclesially and ecclesiastically.

Putin's attack against a sovereign country helps us realize what we can and cannot expect in terms of participation to the synodal process from Catholics in Ukraine, but also from those in other war-torn areas around the world.

They cannot offer a well-crafted synthesis of listening sessions. Their contribution will be of a different kind: less quantifiable, more mystical. Their suffering can teach a great lesson about what it means to be Church in the world of today. And synodality means that we Catholics must discover how we can "walk together" with the Church in Ukraine at this terrible time.

Read more at: The war in Ukraine's impact on the synodal process (la-croix.com)

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment