Women and power in the Church

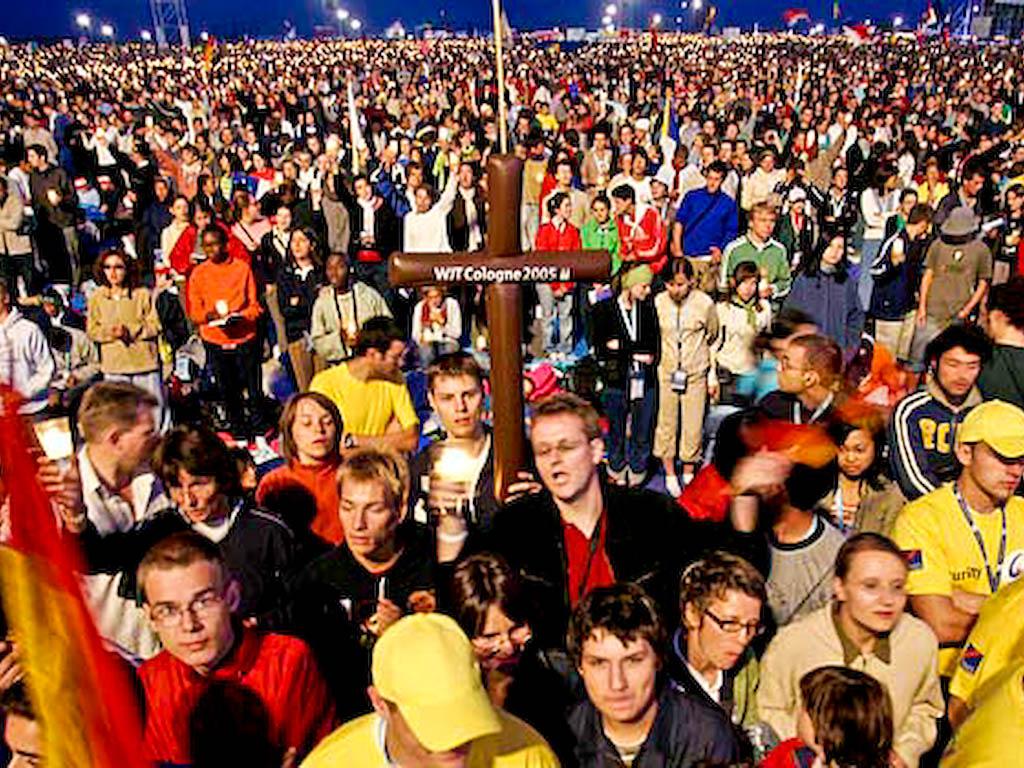

Vita cristiana ed ecclesiale 16.05.2023 Jesús Martínez Gordo Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgIt is difficult - all the more so in an institution as large and diverse as the Catholic Church - that a decision, however limited, does not lend itself to diverse and conflicting reactions. This is what I notice, once again, when I review the stances of many people and groups in the face of Pope Francis’ measure to incorporate - by voice and vote - seventy laypeople (half of them women) into the World Synod of Bishops to be held next October in Rome, aimed to address the always thorny issue of how to govern and structure the Church and how to exercise the Magisterium.

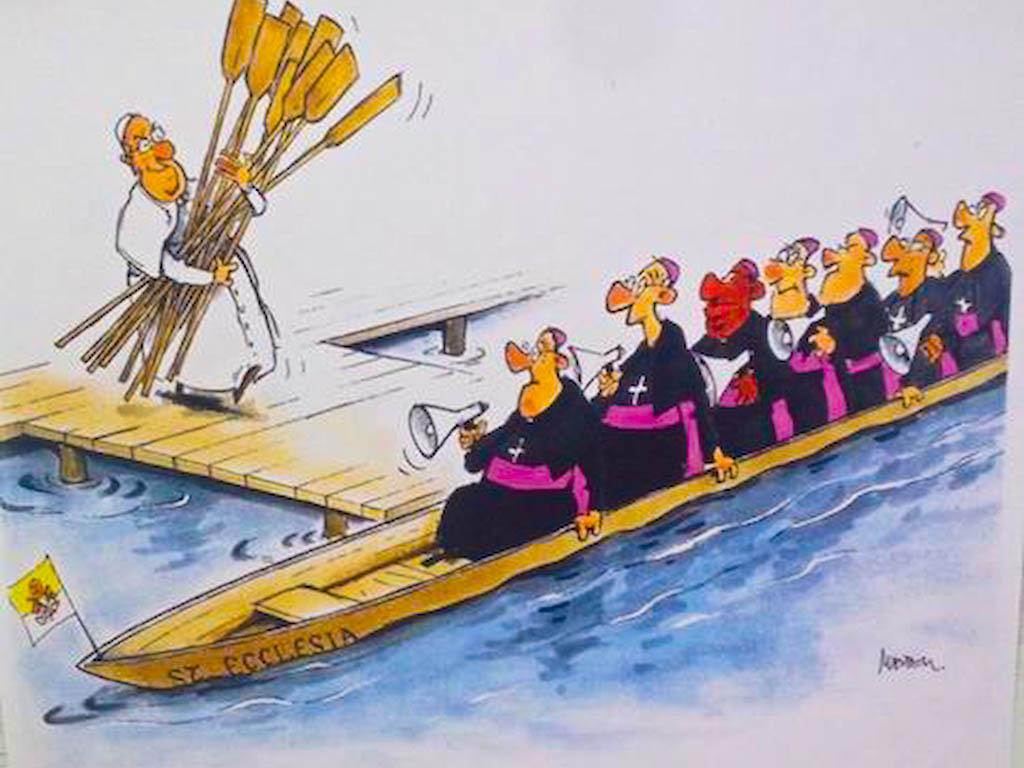

Critical voices have underlined (and, even more, magnified) the contradiction present in Francis' decision. How can it be explained that, in a bishops’ assembly, there are laypeople with the right to speak and vote? Is it not confusing the sacred with the profane?

It is worth bearing in mind that those who make these or similar criticisms do so because they claim that power in the Catholic Church is held solely and exclusively by ordained ministers and, in particular, by bishops; and only by them. They hold it by 'divine mandate or institution', i.e. because, by the will of Jesus of Nazareth, its power and exercise would rest - so they understand it - on the apostles and, from them, on their successor bishops; obviously all male. In no way on the laity; still less on women. The latter can only 'participate' in the sacred power if the bishops are willing to grant them such a 'participation'. This is where, at best, the laity’s power in the government and magisterium of the Church comes from and goes so far. And, of course, moreover that of women.

There is no shortage of those who highlight - starting with this decision - the door opened by Pope Francis, even calling it 'historic' to incorporate - even if only in terms of participation - the laity into this ecclesial governing body, stipulating that half of them must be women.

We already know - we hear - that their number is not much: 70 out of a possible 250 members. But it is a first step that 'opens up' - as Francis likes to say - a process destined for further development, despite the fact that there are many to whom it seems only a drop in the ocean. In any case,' they continue, 'it cannot be ignored that there are not a few Catholics who - in their obvious timidity - find this open door too disruptive, in particular, the irruption of women (even though very timid) in government posts and ecclesial decisions, despite the fact that Francis has said, in every way, he does not intend to promote women’s priesthood.

Finally, I come across those who, being close collaborators of Francis, are trying to mitigate the turmoil caused by this papal decision. They try to do so by saying that these lay people only reach 25% of the synodal capacity. Therefore, there is no risk of a lay revolution in the government, magisterium and organisation of the Catholic Church.

Moreover, as if this were not enough, they go on to say that the bishops - through the seven continental meetings of the Bishops' Conferences - will play a decisive role in choosing the lay people they deem suitable so that, in the end, the pope will appoint them. They will therefore be laymen and laywomen who enjoy the trust of the bishops. These and other considerations tend to 'reassure' those who have been questioning Francis' pontificate for years.

Abandoning the unipersonal model

Recognising the importance of incorporating such a large number of lay people - and, in particular, women - in a world assembly of bishops, I realise that a fundamental problem to be addressed - if the Church is to be credible in the 21st century - continues to be the power management within the Church itself.

It is true that the so-called 'divine institution' of the mentioned power, entrusted by Jesus to Peter, admits different interpretations: the unipersonal one, promulgated in Vatican I (1870); and the collegial and co-responsible one, approved in Vatican II (1962-1965). However, for much of the time since the end of the last Councils, the unipersonal model of government, magisterium and organisation of the Church has continued to prevail at all levels (Vatican curia, dioceses and parishes).

I believe that the time has come to abandon this unipersonal, absolutist and monarchical model, and to start implementing, out of fidelity to what was approved in 1964, the fact that all of God's people - thus not only bishops and priests - are 'infallible when they believe'.

The German Church (bishops, priests, men and women religious, laymen and laywomen) has already opened up an important path in this direction with the so-called 'binding' Synod Way, even if there are those who - at the mere hearing of this adjective - feel shuddered and even nervous. We shall see what Francis will (and can) do.

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment