“Africa must look inward, not backward”

Rivista Africa 26.07.2025 Seguir leyendo Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgSoumaila Diawara, a Malian refugee and political activist, recounts his harrowing journey to Europe and analyses the lingering wounds of colonialism as well as the new forms of domination oppressing Africa. In his new book Tormented Africa, he denounces external but also internal responsibilities, calling for an African political and cultural awakening.

Soumaila Diawara, originally from Mali, is a writer, political activist, and refugee. Raised in Bamako, he became involved in student movements advocating democratic opposition. After the military coup of 2012, he was forced to flee. He crossed the desert and the Mediterranean, arriving in Italy in 2014. A journey at times harrowing: “One night our inflatable boat sank. There were 120 of us, only 30 survived. I stayed in the sea for over an hour before reaching the shore. I saw people die, be killed, I experienced the hell of detention centres in Libya.” After the memoir The Scars of the Safe Harbor, he now releases a new book: Tormented Africa (Abra Books 2025, 318 pages, €20), a passionate and rigorous essay on the wounds of European colonialism and the new forms of domination still weighing on the African continent.

Your book begins with a historical reflection: why is it so important to look at the past to understand today’s Africa?

It is essential because one cannot build a solid future without thoroughly analysing the mistakes of the past, not only those of the colonizers but also those committed by Africans themselves. African politics often remains hostage to neo-colonial logics, sometimes reinforced by corrupt local leaders, who remain among the main culprits for the lack of progress. A genuine assumption of responsibility is needed from everyone, Africans first, to build a freer, more democratic politics addressing the real needs of the people. Greater stability in Africa is not only in the interest of Africans: it is an advantage for the entire world.

What are the most severe legacies colonialism left in Africa?

The most obvious are the authoritarian power structures persisting in many countries. In Togo, for instance, the same family has been in power for decades. In Gabon, the Bongos have ruled for three generations. There are also heavy economic legacies, such as debts contracted during the colonial era that still strangle African states. These are debts imposed by European powers, often between governments and banks of the colonizing country, and they seriously hinder African development.

You analyse different colonial models: who bears the heaviest responsibilities?

Belgium, without a doubt. It is absurd to think that such a small country, which at the time of the Berlin Conference was not even a great power, could commit such atrocities solely in the Congo. We are talking about over 10 million deaths—perhaps even 20 according to some historians—and mutilations inflicted on children to punish parents who did not collect enough rubber. Then there are the Italian atrocities in Ethiopia, such as the use of gas against civilians; Italy had a dark and violent colonial history, and downplaying it is both a historical and moral mistake. Let’s not forget the Nama and Herero genocide in Namibia by the Germans. Stories are often ignored, but they speak volumes.

After more than 60 years of independence, isn’t it convenient for some African governments to keep blaming colonialism for current problems?

I agree. Some regimes, in power for decades, continue to use colonialism as an excuse to justify their failures. But if France, for example, is no longer present in Mali and problems persist, it means we must look inward. One cannot denounce Western imperialism and then submit to other powers like Russia or China. Africa must break free from this dependency logic, stop clinging to victimhood, and begin a profound internal cleansing. Only then can genuine African sovereignty be built.

You also discuss new forms of economic domination: what do you think of China and Russia’s role in Africa?

The form has changed, but the substance remains. Neo-colonialism today presents itself more subtly. China builds roads, schools, hospitals… but often these infrastructures are designed only to connect mines to ports, not to improve people’s lives. Russia, instead, acts as an armed arm, in Mali or the Central African Republic. There’s much talk of ousting the French, but tomorrow could we do the same with the Russians? I doubt it. The new powers act in their own interest. Africa must learn to choose partners based on respect and reciprocity, not ideology or momentary convenience.

Who are today’s most credible African leaders in the struggle for the continent’s economic and political independence?

Unfortunately, few. People are often misled by certain figures: Kagame, for instance, is seen as a Pan-Africanist, but in reality, he destabilizes the Congo and exploits its resources. One of the few who seems genuinely trying to change things, respecting human rights, is Bassirou Diomaye Faye in Senegal. He condemned repression and extended a hand to young people. One can break with colonialism without shutting down all dialogue with Europe. Balance is needed, not populism.

In Mali, a military junta governs today. Is it a response to corruption of previous governments or a new problem?

It is a worse problem. The military in power has favoured a new elite, composed of young people linked to the junta who suddenly became billionaires. It’s a carbon copy of Moussa Traoré’s regime. Anyone daring to criticize is silenced, arrested, persecuted. True opinion leaders have vanished from the public scene. It is an authoritarian system, without transparency or freedom.

What do you think of the Mattei Plan promoted by the Italian government?

Enrico Mattei’s original idea in the 1950s was interesting. But today that plan is no longer relevant. Africa is not the Africa of the 1950s, the population has tripled, challenges are new. Talking about development with 5 or 10 billion is pure propaganda. It is a plan designed more to guarantee access to African resources than to create a true partnership. Something profoundly different is needed.

In Italy, Africa is often depicted as a threat, the source of a migratory invasion. What do you think of these narratives?

I am outraged. These narratives are deliberately constructed to sow fear. Africans in Italy are a minimal part of the migrant population. Speaking of an invasion is false. Moreover, the same government complaining about irregular migration requests 500,000 regular African workers. So why not start with those already here? Regularize them, train them, teach them the language, integrate them? It is absurd to play with people’s lives for a few extra votes.

You also passed through Libya. What do you think of the liberation of General Osama al-Masri?

A disgrace. This man is responsible for rape, torture, slavery. He had a private airport built using migrant labour he called “his slaves.” The Italian government welcomed him with honours, missing a historic opportunity to uphold international law values. It is a moral and political defeat.

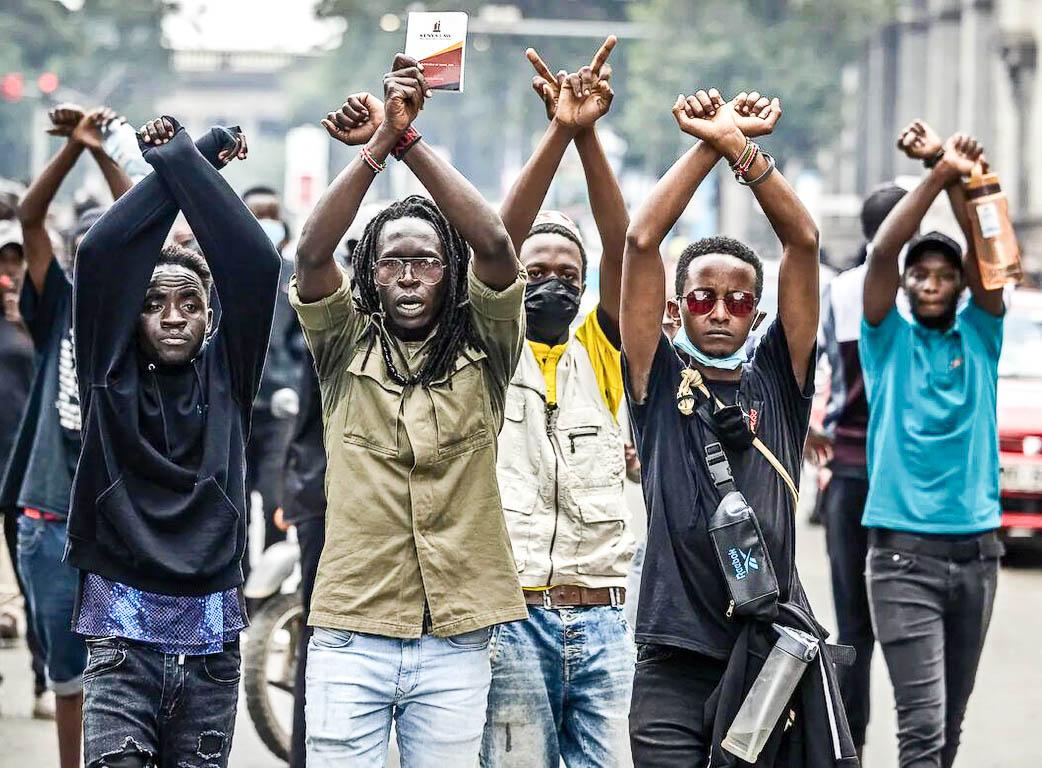

In many African countries, youth protest movements are emerging. What do they demand? Will they really manage to change things?

They demand rights, accessible education, work, and transparency. They want public exams without favouritism, lower university fees, less corruption. They may not succeed immediately, but they are already awakening consciences. Governments cannot arrest them all. The West should also understand whom to cooperate with: the people, not their oppressors.

It is often said that Africa has no future. What is your response?

Africa will surprise again. Its strength comes from suffering, but also from a new awareness. Young people know change will not come from outside. They have the skills, will, and strength to build a future. Africans should no longer be seen as passive subjects. Those who do so feed neo-colonial thinking. Look at Ghana, Botswana, South Africa: Africa can make it, and its redemption will also be a chance for Europe.

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment