COP30: A Good News?

Butembo 20.11.2025 Manariho Etienne Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgUndoubtedly, a series of good intentions and promising proposals, serious planning and commitments — at least in words and even on paper. So many zeros to which history will need to add the initial one that transforms them into wealth for the good of the planet.

COP30, at the moment of its gathering, gives the impression of a shared desire to assemble declarations of principle and political frameworks to establish “good intentions” and “serious planning,” laying the necessary foundations—although not yet materialised—to reach its objectives.

The Zeros. Intentions and Prophetic Projects

Pope Leo XIV, in a video message addressed to the cardinals and bishops gathered in Belém, reaffirmed the Church’s support for the Paris Agreement and called for stronger political will. It was an urgent appeal of faith and moral leadership.

He stressed, in terms of urgency and responsibility: “We are the guardians of creation, not rivals for its spoils,” highlighting that the “window is closing” to keep global temperature increase below 1.5°C. It is not the Paris Agreement that is failing, but the response: “What is lacking is the political will of some,” since stronger actions could create more solid and equitable economic systems.

The Prophetic Voice joined that of the Pope in the Museum of the Amazon — a symbol of creation in suffering — through the regional episcopal conferences of the Global South, insisting on climate justice and total ecological conversion.

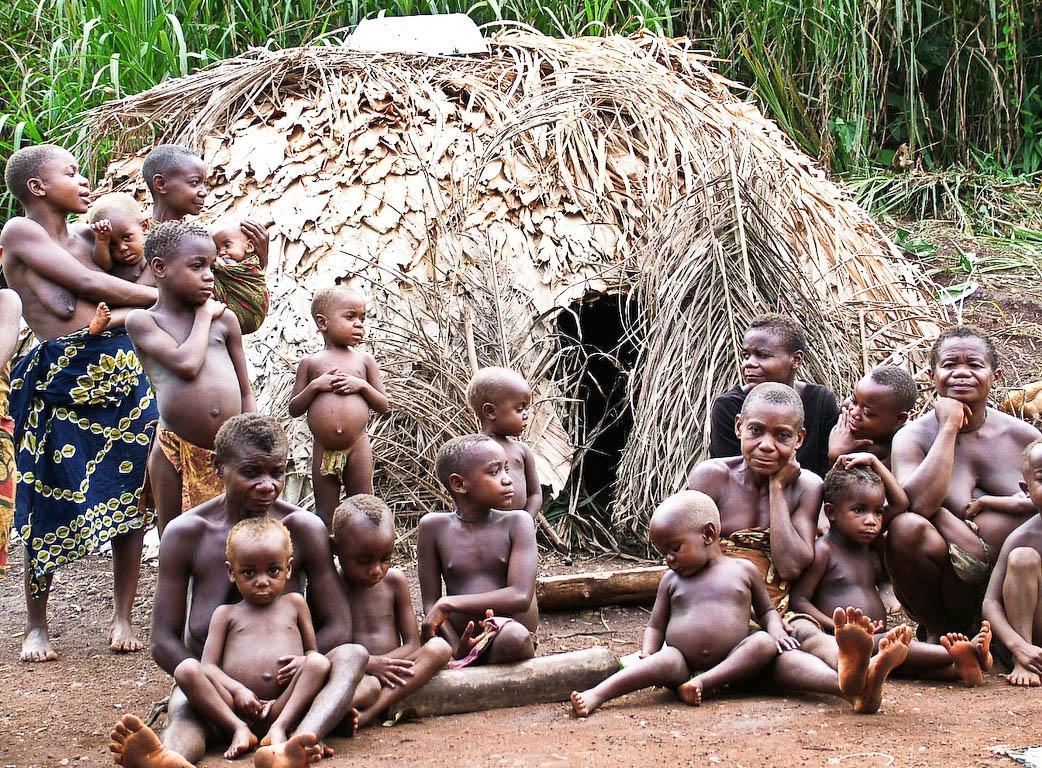

The Belem Declaration, supported by 44 countries, called for Recentring Climate Action on the Human Person and placing the most vulnerable populations at the centre of climate policies.

It was followed by the proclamation of a New Alliance for Climate-Resilient Social Protection and Financing for Small-Scale Agriculture, aiming to harmonise national ambitions with local measures.

This Alliance supports a Plan to Accelerate Solutions (PAS) establishing clear targets, concrete actions, and progress monitoring.

An open letter, signed by more than 1,000 organisations from 106 countries — trade unions, Indigenous peoples, feminist and youth movements, Afro-descendant organisations, peasant groups, environmental defenders and community structures — calls on States to commit to a truly people-centred just transition. This was already stated in the official communication of the 197 Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC): “Ten years ago, the Paris Agreement carried a promise: that climate action would protect the rights and livelihoods of populations, placing the burden of transition on those most responsible for the crisis.”

In this context, negotiations led by governments around the Belém Action Mechanism (BAM) for a Just Transition — a new financial and coordination framework under the UNFCCC — constitute a major obstacle at COP30, as they have deeply divided discussions: The Group of 77 (G77, a coalition of developing countries of the South), allied with China, is opposed to industrialised countries, particularly the United Kingdom and other nations of the Global North. The position of the G77 + China aligns with that of civil society and trade unions regarding Just Transition.

The BAM seeks to translate the principles of Just Transition into a clear and operational plan under the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement, identifying obstacles, opportunities, and international support needed to enable this transition across different sectors, countries, and communities.

Representatives of poor communities expressed optimism that all these initiatives may strengthen adaptation, unlock technological potential within global agricultural systems, and help the international community redefine resilience by transforming vulnerability into strength and ambition into action.

Two major digital tools have finally been launched to support climate-smart agriculture: an open-source artificial intelligence model dedicated to agriculture, announced by Brazil and the United Arab Emirates with the Gates Foundation and Google; and AIM for Scale, an AI tool that could help more than 100 million farmers by 2028 through real-time data. International donors have also announced more than 2.8 billion dollars for farmers’ adaptation and resilience, in order to strengthen global food systems.

A Still Insufficient Symbol

COP30 officially launches the call for proposals for the “Loss and Damage Fund” created at COP27.

The LDCs (Least Developed Countries) hail this opening as a “lifeline” for the most vulnerable, enabling financing for projects between 5 and 20 million dollars.

But resources remain derisory, revealing a critical insufficiency: 800 million USD compared with estimated economic losses for 2025 ranging between 128 and 937 billion dollars.

The Fund must be accessible, transparent, grant-based, and able to disburse rapidly after disasters.

Calls therefore demand capitalisation and massive financing. Climate justice requires responsibility and efficiency: accessibility, transparency, grants rather than loans, and mechanisms for immediate post-disaster disbursement.

The Gap Between Promise and Reality

Ten years after Paris, implementation is seriously delayed.

Inequalities are worsening, and one third of the world’s population lives in severe climate vulnerability.

Negotiations are blocked, and so is the transition, because many still refuse to leave fossil fuels behind.

Consequences on the ground worsen the situation: The Sundarbans — the vast mangrove region between India and Bangladesh, a World Heritage site — Indigenous peoples, climate migrants, agricultural losses, and farming crises caused by salinity, rising waters and climate extremes raise alarms about the future of entire populations. The most striking example is that of the Guaraní people: degraded agriculture, forced migrations, inability to harvest sacred foods.

What Signs of Optimism Remain?

What glimmers of hope make it seem as though the launch of appeals and projects were good news for the most vulnerable countries?

- Justice and Democracy as Drivers of Action

COP30 in the Amazon paves the way for a new political space and increased leadership from the Global South. The absence of the United States allows a more multipolar world order to emerge.

The Escazú Agreement becomes a model for protection of environmental defenders. And OSF (Open Society Foundations, an international philanthropic network supporting human rights and environmental justice) invests 19.5 million USD to support environmental justice in Latin America.

Youth and civil society actively carry visions of governance that are more equitable, respectful of human dignity, and harmonious with nature. - The Driving Role of Civil Society and Philanthropy

Indeed, faced with the inertia of the multilateral system, NGOs and foundations innovate and experiment.

Philanthropy acts as a laboratory, providing space for innovation and risk-taking outside state frameworks. It tests ideas that governments hesitate to explore.

Multilateralism, despite fatigue, evolves rather than collapses, giving way to coalitions built on shared values, while a more flexible and coordinated multipolar world appears to be emerging.

Climate justice is being redefined and speaks of expanded participation, inclusion of the marginalised, equitable management of natural resources and defence of frontline communities.

The Dilemma: Between Promises and Reality

However, despite these few sparks of optimism and despite the “zeros” and a few “ones,” optimism is not dominant across sectors of society and among scientists.

Ten years after the Paris Agreement, the results are disappointing: one third of humanity remains exposed to extreme climate vulnerability and the 1.5°C target remains out of reach. According to UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme), despite progress, the world remains off track: current policies and measures are insufficient and are taking us toward nearly 3°C of warming, also because touching fossil energy remains taboo.

Consequences are already visible: soil salinisation, forced migrations, agricultural losses in the Sundarbans, and the inability of Indigenous peoples to harvest traditional foods.

President Lula called COP30 the “COP of truth,” but in what sense? LDCs warn that inaction is “immoral and illegal”: “We are burning in the heat of a fire we did not light,” protest poor countries and Indigenous populations. Even those who did not start the blaze will suffer its heat unless we roll up our sleeves together to extinguish it.

Haba na haba hujaza kibaba — Little by little, the jar fills — seems to be the comforting motto of those who refuse to lose hope in the future. But will that attitude be enough?

Photo. The Comboni's family members at Belem

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment