The Difficulties of the Anthropocene

Ethic 20.06.2025 Manuel Arias Maldonado Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgTo say we are living in the Anthropocene is to assert that the cumulative impact of human beings on the environment has ultimately destabilised the Earth system, pushing it towards a new state of equilibrium whose features remain unknown. However, we still have the whole epoch ahead of us.

There is something oddly beautiful about the fact that the term "Anthropocene" first emerged precisely in the year 2000, when the Dutch chemist Paul Crutzen spontaneously suggested it—without any written document—during an academic conference held in Mexico. It is, however, a twisted sort of beauty: anyone tempted to claim that the concept was born with the 21st century must remember that, strictly speaking, the century did not begin until 2001… despite our common belief to the contrary. Yet the imprecision is fitting, given that no one knows exactly when the Anthropocene began—and some even deny that it ever truly began. Nevertheless, it exists. Or rather: the phenomena on which this hypothesis rests have been empirically observed; whether we choose to debate their significance and implications is another matter. And indeed, the past few years have witnessed not only the intensification of the green agenda but also its increasing political contestation within polarised societies where populist political styles have gained the upper hand.

But let us proceed step by step. To say that we live in the Anthropocene is to say that the aggregate impact of human beings on their environment has led to the destabilisation of the Earth system, pushing it towards a new equilibrium whose nature we have yet to determine. Climate change is its most familiar manifestation, but we are also aware of ocean acidification, biodiversity loss, the spread of invasive species, urban concentration of human populations, the massive use of plastics, and the rise in waste. All of these phenomena can be explained by human action—though most are side effects, often unintended, of that very action: the Anthropocene, thus, has arrived almost by accident.

Almost: if human beings are characterised by their aggressive adaptation to the natural world—transforming it to suit their needs—modernity has brought with it an increase in our power to intervene. One need only note that the considerable rise in atmospheric CO₂ over the past two centuries stems from the use of fossil fuels: the very energy source that enabled economic growth during industrialisation is now the one endangering the benign planetary conditions that prevailed throughout the Holocene. Hence the fragile consensus around the need to decarbonise our societies; the Anthropocene will be sustainable, or it will not be.

The point is that the Anthropocene is not a natural reality, but a concept intended to make sense of the state of socio-natural relations. It signals that we are living in a “human epoch”: our species has become a global environmental change agent. For some geologists, this change is visible in the fossil record; thus, the Holocene would have ended, and the Anthropocene begun. So far, the official bodies in charge of defining Earth’s geological chronology have rejected this notion; the stratigraphic criteria are not fully met, and they therefore propose describing it as a geological “event”. While natural scientists reach agreement—or not—the rest of us can agree that the Anthropocene is indeed a new historical period; the socio-natural phenomena on which this idea is based—changes in the natural world brought about by the impact of social activity—are not going away. We must become “planetary stewards” putting our house in order.

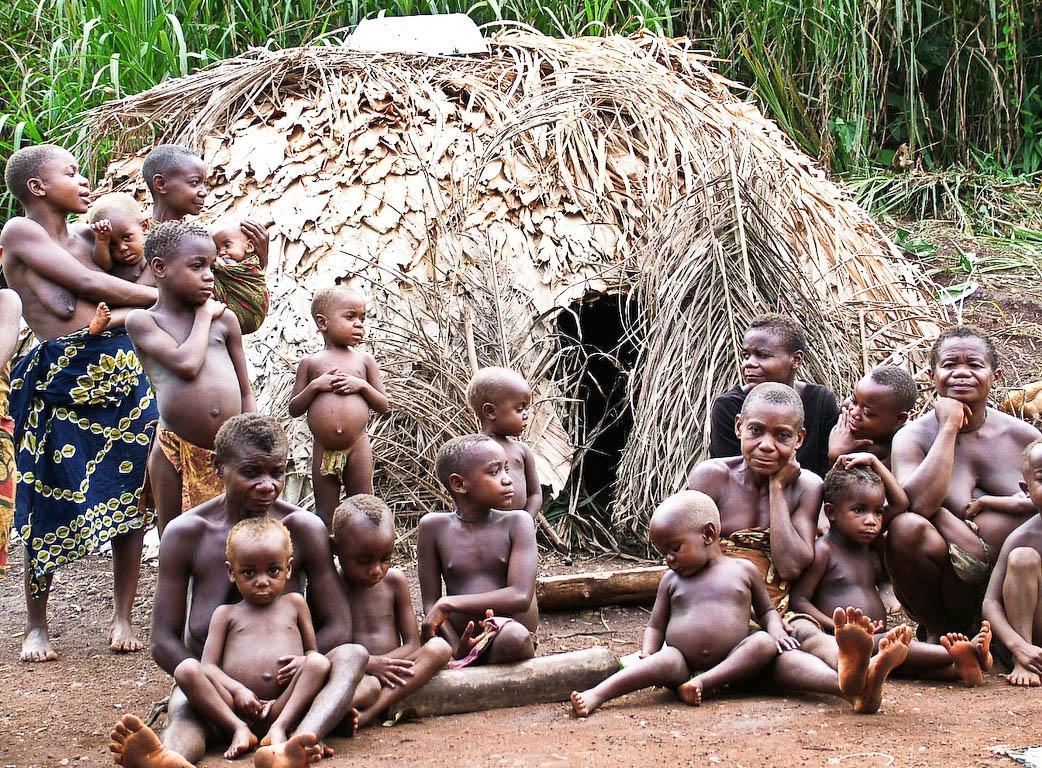

Yet achieving consensus among eight billion people on how to respond is even more complicated. Disagreement is inevitable: what is at stake is nothing less than the abandonment of the energy sources that enabled societal modernisation and the material comfort enjoyed by much of humanity… all without jeopardising the aspirations of the rest to attain similar living standards. Positions vary widely: those who believe capitalism threatens our survival suggest abandoning growth and living differently; their opponents respond that climate models exaggerate and that more pressing problems deserve our attention. In practice, both sides lean towards inaction: some indulge in the fantasy of de-growth, while others cling to immobility.

More balanced are those who advocate making modern societies sustainable through technological innovation, public regulation and cultural change. Yet even here a rift appears: some are in a hurry, while others believe haste is a poor counsellor. If the former place their trust in the state’s ability to transform society through legislation, the latter warn of the risks of ignoring the complex nature of that very society. Not only because good intentions may yield disastrous outcomes—as demonstrated by the growing struggles of Europe’s automotive industry to make its finances work—but also because those who feel unfairly disadvantaged do not remain idle. Just look at the protests by European farmers and middle- and low-income citizens around the world: neither group is willing to accept that political elites fast-track the energy transition without securing its political legitimacy and social fairness.

All evidence suggests that the hurry-on strategy has backfired: the return of Donald Trump to power confirms a global rightward shift that threatens to bring the green agenda to a screeching halt. Even the European Commission under Ursula von der Leyen—who, in spring 2023, attended a de-growth conference organised by the European Parliament—now states that the European Union must refocus on growth. And where is Greta Thunberg? Perhaps we are heading toward a world where climate adaptation takes precedence over mitigation policies; one in which heightened environmental awareness does not necessarily translate into an ambitious green agenda. But there is still room for optimism: the politicisation of the energy transition was inevitable once it entered the public sphere; the emergence of pragmatic voices is, in fact, more than welcome. Much progress has already been made: energy innovation—potentially a driver of growth and a lucrative business—will not be easily stopped. Just ask China! So let’s not go to extremes: things are becoming increasingly interesting, and the Anthropocene is only just beginning.

See: Las dificultades del Antropoceno

Illustration: Óscar Gutiérrez

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment