Peace, the Smallest of Seeds

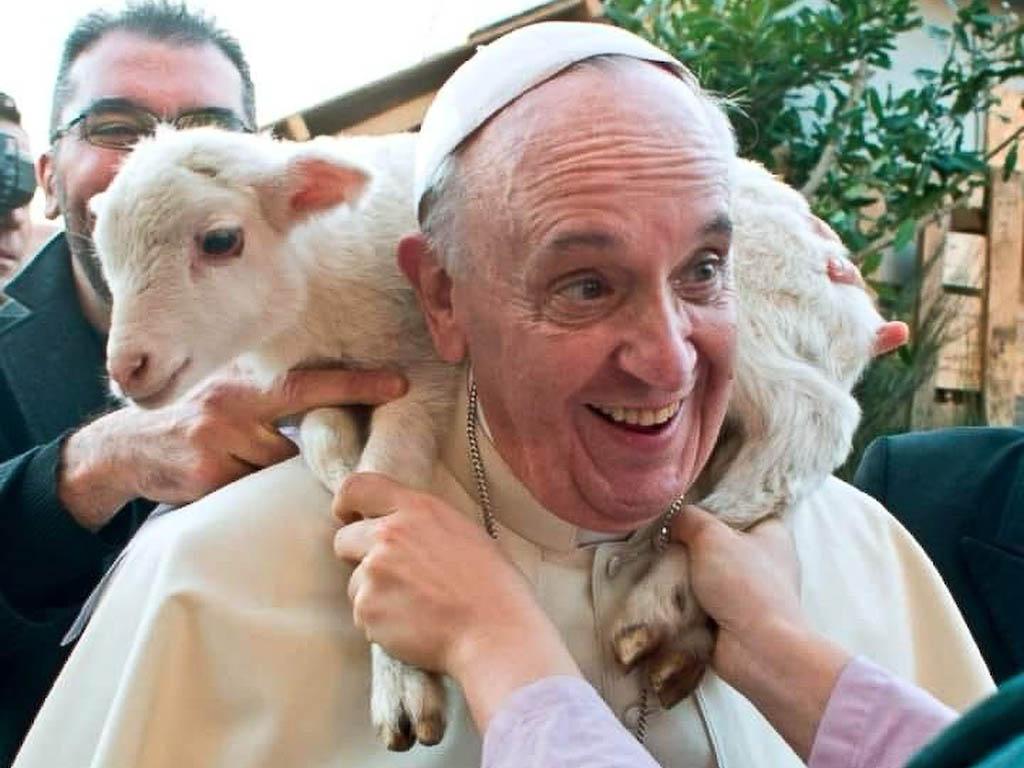

Messaggero di Sant’Antonio 24.03.2025 Luciano Manicardi Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgPope Francis called for “the first sign of hope to be translated into peace for the world,” and adds that much of humanity is devastated by “the tragedy of war” (Spes non confundit 8). What seems utopian to humankind is, for the Christian, hope.

Is peace a utopia? Perhaps. But it nourishes our longing to move in the direction of goodness. A goodness reflected in those places that have taken care of people—small seeds, foretastes of the Kingdom.

Pope Francis asks that “the first sign of hope be translated into peace for the world,” and adds that a large part of humanity is devastated by “the tragedy of war” (Spes non confundit 8). We human beings speak of peace in relation to war and invoke peace as the end of a war. Thus, the concept of peace is subordinated to that of war: peace needs war in order to be conceived. It may be more fruitful to question the “terrible love of war” (James Hillman) that dwells within us, and to recall the words of Heraclitus: “War is the father of all things.”

The Bible, in its many pages soaked with blood, recounts wars and violence, yet dares to expose and denounce war and violence as grave sins. It is totalitarian regimes that conceal violence and ban the word “war,” masking it behind euphemisms. The Bible, instead, faces violence directly, revealing the hideous nature of war—and in doing so, gives voice to the hope of a world freed from war, as envisioned in the prophecies of Isaiah (2: 2–5) and Micah (4: 3–5): “They will beat their swords into ploughshares, and their spears into pruning hooks. Nation will not lift up sword against nation, and they will learn war no more.”

Utopia? Certainly—just like the ideal of a universal fraternity and sorority, another name for the Kingdom of God that lies at the heart of Jesus’ message.

But what is utopia?

“Utopia is like the horizon: I walk two steps and it moves two steps away. I walk ten steps and it moves ten steps farther. The horizon is unreachable. So what’s the point of utopia? It is this: it keeps us walking.” (Eduardo Galeano)

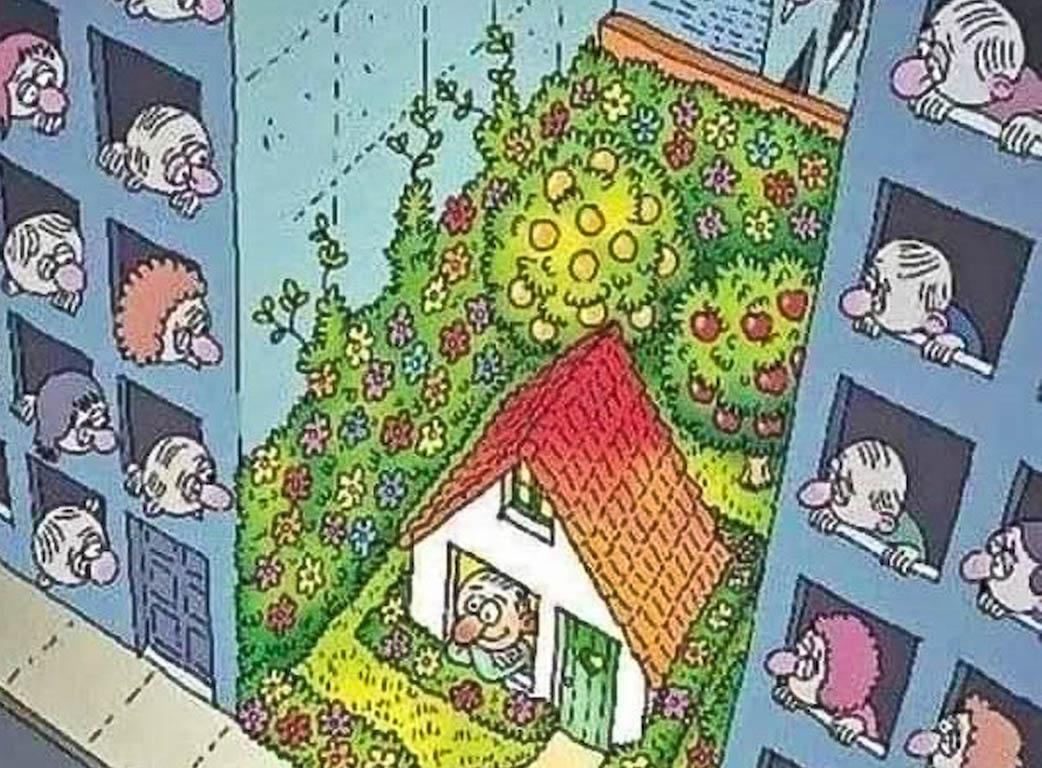

Humanity walks in the present sustained by hope (homo viator spe erectus – “the travelling man, lifted by hope,” meaning the human being is a pilgrim on earth, journeying with hope as his guide and support). Since authentic hope requires glimpses of reality that already reveal something of its fulfilment, we must give space to the future by creating eutopias—real places and experiences shaped by the meaning of the prefix “eu”: good.

Places of sharing and conviviality, participation and solidarity, the exchange of stories and narratives—spaces that give meaning to the present and open us to the future. Eutopias are places of human salvation, where every human being is valued in full dignity simply by virtue of being human, before any qualification or status. These are places where the word “peace” finds its full weight and richness, embracing the biblical concept of shalom—a global notion that includes relational and social, psychological and spiritual, economic and political dimensions.

To this end, we must cultivate a culture of care, the precise opposite of the culture of war. In war, the other is an enemy to be eliminated, the environment is destroyed, the logic of protection is replaced by destruction, and solidarity gives way to enmity. Tragically, the terrible love of war makes the culture of war far more dominant than the culture of care—as seen during the pandemic, when military metaphors were used everywhere, though the true image was that of care.

We might ask: aren’t eutopias themselves just utopias? The answer lies in real life. Think of Nevé Shalom – Waahat as-Salam, a peace village founded in the 1970s by Bruno Hussar west of Jerusalem, showing the real possibility of peaceful coexistence between Jews and Palestinians. Or Rondine, the Citadel of Peace, near Arezzo, where young people from warring nations live together and receive education in peacebuilding. These are only two examples, but they show that only love for one’s enemy (not merely for one’s neighbour) can defeat the terrible love of war. “The greatest hero is the one who turns his enemy into his friend.” (Abot de Rabbi Nathan A 23)

And aren’t Christian communities, as Cardinal Martini described them—alternative communities that prioritise values neglected by the world such as service, inclusion, hospitality, forgiveness, recognition, and sharing—also eutopias?

And what about those forms of “resistance-creation,” describing new ways of life based on simplicity, solidarity, and alternative models of relationship and consumption, as discussed by Benasayag and Cohen in The Age of Unrest. Letter to Young Generations?

One may say these are “small” experiences. But it is precisely in their smallness that they reflect the logic of the Kingdom of God, where the smallest seed becomes the largest tree.

Look: Pace, il seme più piccolo

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment