Red Rags and Community Pots: The Cry of the Invisible in Latin America

Interris.it 26.07.2020 Damiano Mattana Translated by: Jpic.jp-orgThe risk for South America, linked to the pandemic and beyond, is to find itself with 29 million more people in poverty. A red alert for the social fabric of the continent (Translated from Spanish by Alissa D’Vale).

Twenty-nine million new poor. This is a concrete risk currently in Latin America as it is one of the regions of the world most affected by the novelty coronavirus pandemic and of everything that came with it. A dramatic picture, for a continent that shortly before the advent of Covid-19 had experienced a season of social turmoil that had undermined its stability practically from north to south. Coronavirus has entered the gaps of the social fabric of South America, further digging into inequalities, increasing conditions of poverty and in some cases creating new ones.

Latin American Alarm

And this is where the alarm grows: the risk, highlighted by Action Against Hunger is that the number of new poor still increases, even reaching 8% of the population (67 million people). A scenario that crosses the continent even beyond the Panama Canal, contributing to the nefarious possibility – already highlighted by the UN – that the Zero Hunger goal for 2030 not only fades, but finds itself faced with new contexts for suffering.

Interview with Benedetta Lettera, responsible for Latin America’s Action against Hunger (ACF).

Latin America is the geographical region that in the past five years has suffered the most from the increase in food insecurity worldwide. A significant figure, which explains the extreme conditions of general difficulty for the countries in the continent. Are the social problems experienced by some states, even in the last year, sufficient to justify this increase or do other factors also play a role?

BL. In the past four years, after a series of encouraging data regarding access to basic needs for the population, the number of malnourished people had already grown by nine million. The reasons identified by ACF are numerous: economic, social and political ones.

Here are some specific examples linked to some representative countries: before the pandemic, in Peru, 20% of the population already lived in a condition of poverty; in Guatemala, which has one of the most fragile health systems in Latin America, with 13 doctors and nurses for every 10,000 inhabitants, as well as economic uncertainty, affected more than 70% of the population: these are people who are often unemployed and who lack social absorbers; Colombia, even before the coronavirus emergency, was dealing with the abandonment of rural areas after many years of armed conflict. So, these critical issues, in a region in which one in three people lived in a condition of food insecurity, have been exacerbated by the effects of Covid-19 and containment measures on a fragile economy based on ‘informal’ work. In short, the coronavirus has triggered the ‘perfect storm’ by exposing many people to the issue of hunger and food shortages.

Latin America, like Central America, has been framed by the UN at the center of a dangerous drift, with the risk of gaining 29 million new poor people. In the face of the limitations imposed by the coronavirus, what strategies can be put in place to contain the new waves of poverty?

BL. The needs of each country and the underlying causes for food insecurity in various communities are different, therefore, each case must have a specific response – this is the path taken by ACF. In Peru, for example, we have promoted a coordination network to provide food to the most fragile communities; in Colombia, staff continue to monitor the nutritional status of children in border areas; in Guatemala and Nicaragua, the organization is engaged not only in the supply of hygiene kits but also in training local staff for the sanitization of healthcare facilities. These are just a few examples, but I think they are useful for understanding how a differentiated intervention in Latin America should be structured to meet the numerous needs of local populations.

In recent days, the WHO has also highlighted a serious risk for indigenous peoples, probably the most vulnerable, not only to coronavirus but also to other diseases. Are they also considered for protection measures from a hygienic and sanitary point of view?

BL. Absolutely: the organization, for its part, is collaborating with local authorities on the topic of virus prevention through awareness campaigns and the distribution of personal protective equipment and hygiene products. On a more general level, Action Against Hunger is working to further develop prevention activities of Covid-19, adapting them to the characteristics of the context and the particularities that the communities in the region present. I am referring to the supply of protection tools for healthcare personnel, of disinfection products, clearly giving priority to access to food and safe water.

The increase of the conditions of poverty for another large portion of the population could make access to food resources extremely difficult, as well as affecting productive systems. Is there a risk that the drift will worsen problems such as social inequality?

BL. Faced with the data on world hunger released by the latest SOFI in Latin America and globally, it certainly becomes impossible to guarantee the achievement of one of the most important development goals of the millennium: ‘Zero Hunger.’ In the same way, this circumstance risks exacerbating the social inequalities, which are also some of the best-known structural causes to increase hunger, making the hope of the 2020 Agenda of reducing all those ‘weights’ that undermine the natural and more ‘just’ development of a territory complicated.

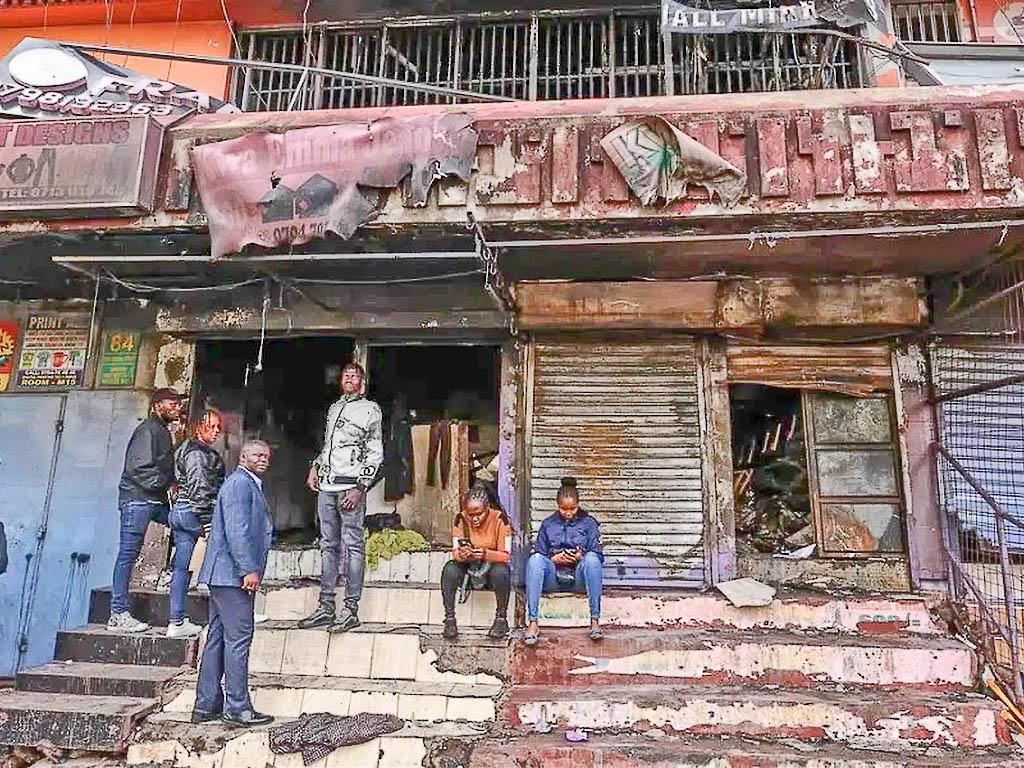

Community pots in Lima and red rags in Bogotá: two symbols of the social emergency experienced by these cities and their countries. But also requests for help so that the contexts of poverty and insecurity do not remain invisible.

BL. The South American populations also communicate, in some way, the difficulties experienced by their respective communities. Or they respond to the crisis by utilizing old customs as it was in the 1990s, when another serious economic and food crisis was underway. In Peru, for example, the decrease in income received by workers or the lack of income linked to the coronavirus emergency risks changing the eating habits of families: many have replaced more nutritious and expensive foods with cheaper ones. Therefore, everyone organizes themselves as they can by extending their network of solidarity with the closest people. Colombia has been chosen to pronounce the unease through a striking gesture: the red rags are an unequivocal signal of unmet needs, of an emergency that adds up to other crises, of needs to which, we at ACF, are trying to respond in a real race against time.

Original Text: Stracci rossi e pentole comunitarie: il grido degli invisibili in America Latina

See more:

- Address ‘unprecedented’ impact of coronavirus on Latin America and the Caribbean, urges Guterres

- Pandemic Could Push 45 Million in Latin America Into Poverty: UN

- Hungry neighbors cook together as virus roils Latin America

- During Colombia's Coronavirus Lockdown, Needy Residents Signal SOS With Red Rags

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment