Almost 400 Pairs of Shoes

Comune Info 15.03.2025 Nodo solidale Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgOn 5th March, the collective “Guerreros Buscadores de Jalisco” uncovered something that exposed a new level of cruelty from those in power in Mexico: an extermination camp run by the Jalisco New Generation Cartel, one of the country's most brutal criminal groups.

In a ranch in Teuchitlán, a rural area an hour from the city of Guadalajara (and just half an hour from a military barracks), behind a gate like so many others in Mexico, the collective “Guerreros Buscadores de Jalisco” — not the authorities — discovered three crematorium ovens filled with human remains. Alongside these, they found around 400 pairs of shoes and hundreds of other personal belongings: bracelets, earrings, caps, backpacks, and notebooks listing long columns of names.

This is the sheer scale of horror. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people executed with chilling precision, leaving behind a macabre scene of systematic extermination. The mountain of shoes is a gut-wrenching image, evoking the worst massacres in human history.

Jalisco state officially records 186 clandestine burial sites. Tlajomulco de Zúñiga is the municipality with the highest number, totalling 75 clandestine graves. The affluent, polished, tourist-friendly capital, Guadalajara, is littered with stories of enforced disappearances and violence. Monuments have been turned into living memorials, covered with photographs and banners bearing the faces of the missing.

For over fifteen years, collectives like these have joined Mexican civil society in denouncing this dirty war — a war often glamorised or distorted in TV series about the drug lords. It is a war built on obscene amounts of money, trafficking not just drugs but human lives whose bodies are beaten, raped, exploited, tortured, then dismembered, dissolved in acid, burnt, vaporised, and scattered into oblivion.

Victims include young men deceived with false job offers, children snatched from city corners, and teenagers tricked into recruitment. But a significant number are women — girls, young women, and adults — trapped in webs of trafficking, abuse, and torture. This factory of terror has led to 123,808 people officially listed as “disappeared” as of 13th March 2025, according to the National Register of Disappeared and Unlocated Persons. These figures surpass even the horrifying numbers of forced disappearances under the Chilean and Argentine dictatorships.

In Mexico, most victims are not political activists but ordinary people. This reduces the public outcry over a crime of staggering brutality. Over the past six years alone, more than 50,000 people have disappeared under the self-proclaimed “Fourth Transformation” centre-left government — a name that only highlights the government’s responsibility for this deep social wound.

When adding the murders since December 2006, the start of the so-called “war on drugs,” the official death toll reaches 532,609 as of 29th January this year. More than half a million people killed, at least 250,000 of them during the current centre-left administrations.

A War of Territorial Fragmentation

How is it possible for such horror to pass almost unnoticed? The core reason for this Mexican anomaly is not just denial, but the way society itself has side-lined this violence from political discourse and even from the definition of “war.”

“Bombs are not falling from the sky yet,” people say with bitter irony. “We’re not as bad off” as in Palestine, Syria, Kurdistan, Sudan, or Ukraine — even though the death toll might be similar or even worse.

This is not a conventional war between standing armies, nor a typical asymmetric war fought between state forces and “internal enemies.” Instead, Mexico’s conflict is marked by an indiscriminate multiplication of armed groups, each with high firepower. These groups battle in fragmented, violent skirmishes spread across the country. The violence raises the civilian death toll while economic, political, and social life carries on — albeit with frequent blackouts and interruptions.

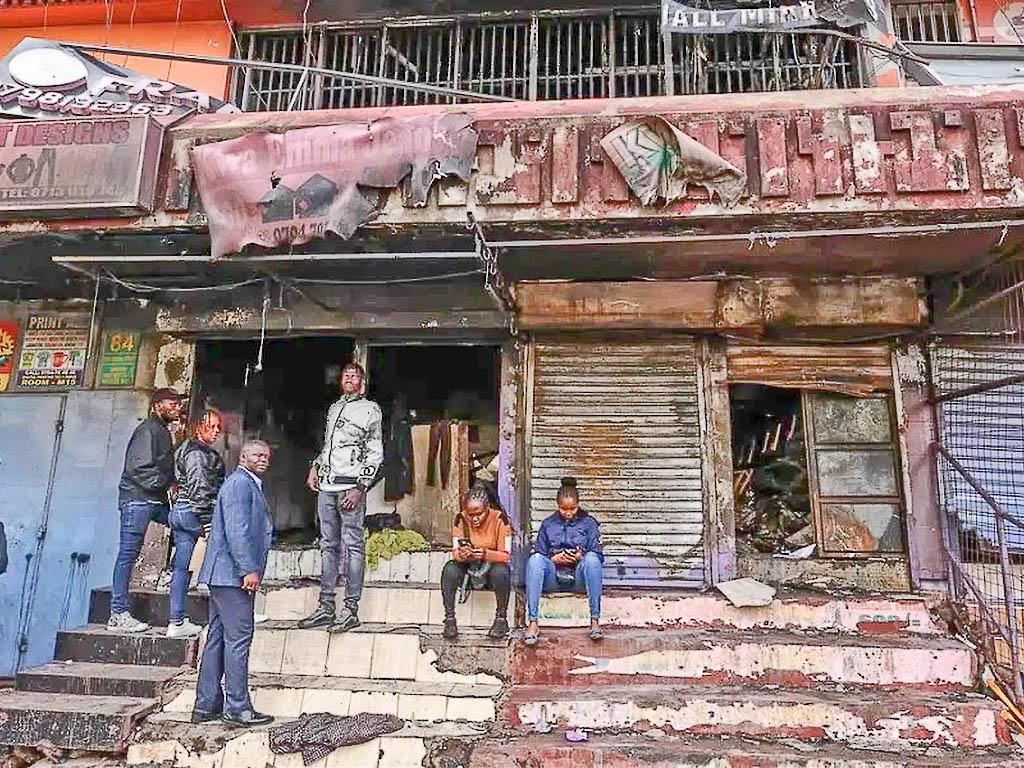

This is a “war of territorial fragmentation.” Areas most affected by offensives and counter offensives, raids, disappearances, and forced recruitments are rural and semi-rural zones like Teuchitlán, where the Izaguirre ranch extermination camp was found. Industrial zones, borderlands, deserts, coasts, and mountains have long been carved up by different power groups controlling routes, crops, and human trafficking. Peripheral populations, often Indigenous or peasant communities, are invisible in the news and sometimes even in official statistics.

When violence reaches cities, it becomes visible, newsworthy, even though public outrage soon evaporates under fear of reprisals. Violence dies down in one place, only to flare up elsewhere.

Large cartels, relatively stable until the late 1990s, were shattered by state military interventions, particularly after the alliance between the Mexican state and the Sinaloa Cartel in 2006. This fragmentation led to an explosion of over 240 armed groups, according to the Ministry of the Interior. These splinter groups manage illicit activities like extortion, prostitution, kidnappings, arms and drug trafficking at the neighbourhood and village level.

The proliferation of armed actors has Balkanised the country, creating “off-limits” areas or territories under de facto curfews. Meanwhile, these criminal structures are logistically supported by state security forces. Officially branded as “corrupt,” they are, in truth, structurally intertwined with the illegal economy, sometimes even fighting each other.

Recently, in an effort to clean up his image and reorganise the flow of cocaine and migrants in southern border areas towards defined interests, Chiapas governor Eduardo Ramírez ordered a crackdown. This resulted in the arrest of 270 police officers and at least three mayors in five cities — implicit clear proof of the collusion between the state and organised crime.

State and crime are not two opposing blocks. Rather, Mexico resembles a vast marketplace where agencies, local offices, pressure groups, judges, politicians, and bureaucrats — along with various armed actors, uniformed or not — compete and collaborate to secure their share of the country’s resources and, crucially, its cocaine transit routes demanded by the United States.

Criminal Economy as Capitalist Production

The criminal economy represents a reorganisation of territorial control and plunder, a phenomenon epitomised in Mexico's “war of territorial fragmentation.” Historically, Latin American states have used armed forces to aid capital accumulation, particularly against Indigenous peoples, workers, and peasants resisting exploitation.

Popular resistance — sometimes armed — was once a fierce, organised struggle against state power, oligarchies, and corporate giants. Mexico’s history is rich with such movements, from the wars of Independence to the Revolution, both largely driven by peasants, Indigenous communities, and, later, workers.

However, after the 1994 Zapatista uprising gained widespread support, overt military repression became politically costly for the Mexican state. Consequently, the use of cartel hitmen as a tool of repression evolved into a systematic method for seizing strategic territories. Criminal groups depopulate areas through terror, clearing the way for economic projects like mines, tourist resorts, ports, or dams — or simply to reorganise local resources and labour in favour of the “winning” faction.

What once involved mercenaries in state service has morphed into a network of regional and local criminal enterprises. These operate independently but remain allied with the state, terrorising populations for their own profit while pursuing the shared goal of unlimited enrichment. This is not repression against guerrillas or activists but a new form of governance — flexible, adaptive, yet ruthlessly applied across the entire population.

This mechanism perpetuates capitalism’s commodification of everything, from land to human beings, while serving a strategic role in the ideological war: depoliticising class struggle and resistance against plunder.

Organized crime, called "narco," has become the armed wing of economic power, placing the victims in the quicksand of doubt: were they killed for their social struggle or ensnared in some obscure racket? Who is really the author of the crime? The impact on public opinion of a murder committed by the police or the army in a political or guerrilla clash, or during a demonstration, is not the same as a murder, with the same objectives, carried out by hitmen linked to criminal groups, during the "normality" of daily life.

The same applies to forced disappearance. Victims vanish into darkness, the executioner becomes invisible, their political significance is diluted as their fate becomes just another “common crime,” unworthy of serious attention. A clearly political murder – dramatically recurrent in the history of class struggle – prompts cries of “It’s the State!” Social movements rally against it, the management of the State is called into question and the government held accountable. And, it becomes the "natural" target of popular anger, denounced by social movements fighting against the violence of the army and the police, armed wings of power and "traitors," like the State, of the social pact with the people, who support them. However, when the perpetrators are ruthless entrepreneurs, without uniforms or rules of engagement, without an ethic or social pact, how does one rebel? Against whom is social anger directed and how can people organise resistance? Who becomes the focus of public anger?

Though there are heroic exceptions, confronting a faceless, amorphous enemy embedded in the social fabric — like the mafia — is an enormous challenge.

Uncomfortable Questions

Amid counter-information campaigns, sceptical questions persist: “Is there really a war in Chiapas? Is all of Mexico really like that?” “I went on holiday there, and it seemed perfectly fine to me!”

Such remarks trivialise the scale of the horror, downplaying the methodical operation of extermination camps and the political use of the so-called “narco phenomenon.” Mainstream media analysis is shallow, focusing on folkloric, anecdotal, or even glamorous aspects (such as Forbes listing El Chapo among its billionaires). These narratives distract global audiences from understanding the real problem.

And there is also the normalization imposed by society itself as a way to survive: you leave home, you go to work or to the supermarket, suddenly there are gunshots… You wait, in some improvised shelter, for the shooting to stop so that you can resume your daily routine. If the message arrives that the neighbour’s daughter has “disappeared,” you read it with a sigh, make it circulate through chat groups, and then you go back to your daily tasks—perhaps whispering a prayer, quietly hoping it will never happen to your own daughter, a relative, or a friend.

In Mexico, life seems to flow as usual: children go to school, sometimes they are closed because of a shootout, but the children know—just like in the case of an earthquake—that they must crouch under the desks or lie flat on the ground: gunfire is experienced as yet another natural disaster, internalised and faced as such. Between media trivialisation and societal desensitisation to violence as a survival instinct, the ashes of burned bodies are swept under the rug of normality.

All this, despite certain moments of outrage, rebellion, and popular protest: it happened in 2011 with the Movement for Justice with Dignity, in 2014/2015 for the 43 victims of Ayotzinapa, and with the creation of “self-defence” groups in indigenous territories. Meanwhile we have half a million people murdered, over 120,000 disappeared, and the discovery of extermination centres in this vast mass grave called Mexico.

A crime against humanity was being perpetrated on the doorstep of Mexico’s second most important city, where people were lured from bus stations, subjected to physical and sexual abuse, incited to kill, and—if they survived the hell—forced to become hitmen, turned into machines of death for the production and accumulation of wealth.

The crimes at the Teuchitlán ranch — raided by law enforcement in 2017 and again in September 2024 without “noticing the ovens or other details” — lay bare the complicity between crime and the state. Running a facility for physical elimination of this magnitude requires silence, if not outright support, from political and judicial institutions.

The pressing questions are grim: How many other extermination centres are operating with impunity in Mexico? How long will the world look away, allowing companies, governments, and their armed wing to cruelly dispose of people and their future? How long will people accept living in fear and terror?

And for global citizens: how long will narco series and thoughtless tourism colour conversations about Mexico? How long will we believe that listening to those “two news stories” on Saturday night without reacting doesn’t make us complicit?

See the full text: 400 paia di scarpe

Photo from Desinformemonos, where other articles on the Teuchitlán ranch can be found.

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment