In the silence, debt crushes fragile countries

Avvenire 27.06.2025 Paolo M. Alfieri Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgThe new UNCTAD report highlights that 3.4 billion people live in countries spending more on debt interest than on health or education. Yields on African ten-year bonds skyrocket.

While diplomacy speaks only of weapons, war, and defense, the silence surrounding development financing is becoming ever more deafening, despite the UN Conference on this issue opening these days in Seville, already marked by the announced absence of Trump’s USA. Virtually ignored by the media, the UN agency for trade and development (UNCTAD) released its annual report yesterday in New York with alarming new data on global debt, especially concerning developing countries, whose economies are being crushed by interest payments owed to private, public, and multilateral creditors.

In just one year, the report “A World of Debt” confirms, the total net interest on the debt of vulnerable countries increased by 10%, reaching $921 billion, with these countries being forced to borrow at increasingly higher rates on the global credit market. Overall, global debt has reached $104 trillion (up from $97 trillion in 2023), with one-third of this amount, $31 trillion, being the debt of developing countries. Over the past ten years, debt in fragile countries has grown at twice the rate of that in advanced economies.

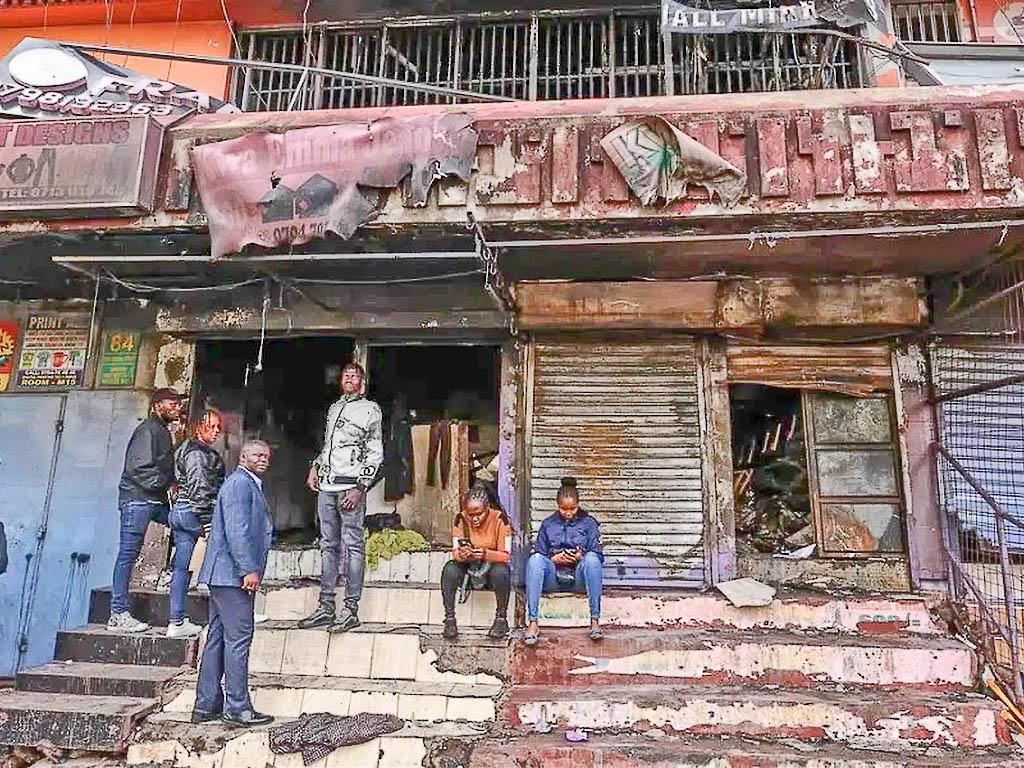

While global aid is collapsing — especially U.S. aid linked to the USAID program, but also aid from several European countries — fragile nations struggle to increase their tax revenues, due to the largely informal nature of their economies and the lack of transparency and adequate infrastructure. Now, UNCTAD points out, 3.4 billion people worldwide (up from 3.3 billion a year ago) live in countries forced to spend more on debt interest than on health or education. This affects 61 countries, compared to 54 last year. The result is that access to basic services remains a distant dream for a large portion of the global population, fuelling discontent in local communities and leading to violent street clashes, as recently seen in Kenya.

Developing countries have also experienced a net outflow of resources for the second consecutive year, repaying foreign creditors $25 billion more in debt servicing than they received in new disbursements, resulting in a negative net resource transfer. Moreover, the credit market offers no leniency to fragile states. Perceived as “riskier,” with little bargaining power, developing countries have seen their bond yields soar. An African ten-year bond yields on average 9.8%, UNCTAD reports, a Latin American bond 7.1%, and an Asia-Oceania bond 5.5%, compared to an average of 2.8% for a U.S. ten-year bond between 2020 and 2025. This means fragile states must offer higher returns to creditors just to secure fresh funds to keep functioning.

Debt restructurings, in cases of payment defaults by poor countries, have in recent years been marked by lengthy and difficult negotiations, partly because the credit market is increasingly dominated by private players, while there have already been 14 defaults in 9 different countries since 2020. In recent days, the Vatican Jubilee Commission, appointed by Pope Francis, has issued an appeal for the reform of the global financial architecture, so that it serves people and the planet and does not punish the poorest in the name of profit. To achieve this, the Commission suggests promoting sustainable development financing aimed at long-term socio-economic goals with concessional rates, and improving current debt restructuring policies by making them more timely, practical, and based on growth rather than mere austerity.

See, Nel silenzio il debito stritola i Paesi fragili: interessi a +10% in un anno

Photo. The remains of a burned shop in Nairobi, in recent days, during anti-government protests – Ansa

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment