Without Moral Bonds, There Is No Sense of the Common Good

Ethic 27.10.2025 Pedro Silverio Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgVictoria Camps (Tarragona, 1941) is one of Spain’s leading contemporary philosophers. A major figure in the field of ethics, she has just published ‘La sociedad de la desconfianza‘ (The Society of Distrust - Arpa, 2025), in which she reviews the major mistakes we are making as a society and invites us—always from a critical perspective—to rethink why we have come to this point and how we can correct our course. One thing is clear to her: the concept of freedom has been distorted by excessive development, and we have forgotten how to cooperate as individuals living together in society.

In your previous book, Tiempo de cuidados (A Time for Care), you discussed the need to care for one another as a society. This new book seems to go a step further: if we are unable to care, we should at least try to regain trust. You say that urgent changes are needed. Are you referring to revolutionary changes, a complete overhaul, or partial reforms?

I don’t think revolutions or wholesale amendments will take us anywhere. We need to think in terms of reforms—specific reforms. These may be small, but they address serious problems that arise at each moment and evolve over time.

For example, we now face a housing problem, which is one of the clearest signs that we cannot rely on the guarantee of a fundamental right. Reforms are necessary, and in the case of housing, this is very evident.

The welfare state should ensure that right, but it doesn’t—and this obviously creates distrust. The right exists, even if it is not constitutionally recognized as a fundamental right, but there should be a guarantee from the State—especially from one that calls itself social—to ensure it. That is not the case.

This clearly generates distrust: we have the principles but not the deeds. What will help us recover trust is the move from principles to facts. When we see that certain expectations are truly fulfilled, trust will return.

You argue that social change stems more from mental frameworks than from legal reforms. In times of polarization, what kind of mindset do you think could prevail, and with what consequences?

More than mental frameworks, I attribute distrust to a very atomized notion of freedom.

Individuals act like nomads focused only on themselves, understanding freedom as doing whatever they consider most convenient for their own benefit.

There is a lack of social bonds and cohesion that would nurture the sense of collective duty—a shared responsibility to tackle common problems.

This dimension of social cooperation has not been achieved by liberal democracy alone. We have not added anything that fosters cooperation, commitment to the common good, or resistance to indifference.

The State and institutions are largely to blame, but individuals also bear responsibility: civil society shows little determination and willingness to face today’s major challenges.

In the book, you say that we still lack clarity about the kind of society we want and how to get there.

Yes, but we shouldn’t try to define a perfect society—that’s what utopias did. A perfect society, such as a completely state-controlled one, has proved dangerous and leads to totalitarianism.

What we must do is genuinely address new needs. We need to correct what is failing or not working at all, rather than trying to design a perfect society—because no one knows what that would look like.

We will move toward improvement gradually, by correcting society’s dysfunctions.

One such dysfunction is the concept of freedom. Has the notion of freedom been corrupted to the point of creating a kind of social anarchy?

I wouldn’t call it anarchy in the sense of rejecting the State. Rather, we delegate to the State issues that we might better resolve ourselves.

Above all, there is no commitment to a common good in which we all participate. The prevailing concept of freedom today is, philosophically speaking, a negative rather than a positive freedom.

It is a freedom that does not ask: “Why do I want to be free?”, “What does freedom commit me to?”, “What duties does my freedom entail?”, “Do I have any responsibility toward society?”, “Is what I’m doing the best not only for me, but for the community as a whole?”

We no longer ask ourselves these questions.

That is the concept of freedom that now falters—and it does not help us build a demos with a shared sense of being that would make us all more democratic, more caring, more fraternal, more respectful, and more equitable.

Speaking of building that demos-people, you have praised Angela Merkel’s “culture of welcome” during the 2015 refugee crisis. Is the lack of that culture among our political leaders, amid a rise in identity politics, an example of collective political failure?

Yes, because it runs counter to a fundamental principle: the recognition of every person’s dignity. That principle should lead to hospitality and openness—something that is clearly absent when we discuss migration policies.

There is no real will to welcome those who come seeking help and protection.

Moreover, as almost everyone recognizes, the arrival of migrant populations does not harm us—neither in terms of employment, social services, taxation, nor public service funding.

It is, in fact, a form of help, but we fail to see it that way. The immediate response is rejection of the other, simply because they are different, uncomfortable, or have a skin colour that displeases.

One of the central themes of the book is education. You point out the paradox that although we have eradicated illiteracy, we have not improved morally. Why is that?

I believe we have not resolved what we call “values education.” Firstly, the term itself is too vague—we haven’t found the right approach.

Talking about “civic education” is somewhat clearer and more concrete. But are we really educating to form citizens—people who can correct themselves within a consumerist notion of freedom, who can commit to the world they live in, who think of others and learn to think for themselves?

This last idea is the maxim introduced by Kant: the sign of an enlightened community is its ability to overcome immaturity and learn to think independently.

This transmission of the value of independent thought, social commitment, self-restraint, and delayed gratification—does education convey this? I don’t think so.

Even moral education has been simplified into a subject to be taught. It has become, as we now say, just another “competence.” We should explain what “moral competence” actually means, because no one does.

It might mean much more than what is currently taught by adding a few hours of ethics.

Aristotle made it clear, and I always repeat his lesson: “Morality is not taught like any other subject.” It is not taught like mathematics or geometry—it is taught by example, by imitation, by creating situations where moral formation is present.

That is how one learns to distinguish what should and should not be done. That practical effort, not merely theoretical, is what I do not see today.

Turning ethical formation into a purely theoretical subject is not the right approach: it helps to understand concepts and moral reasoning, but practice must be learned differently.

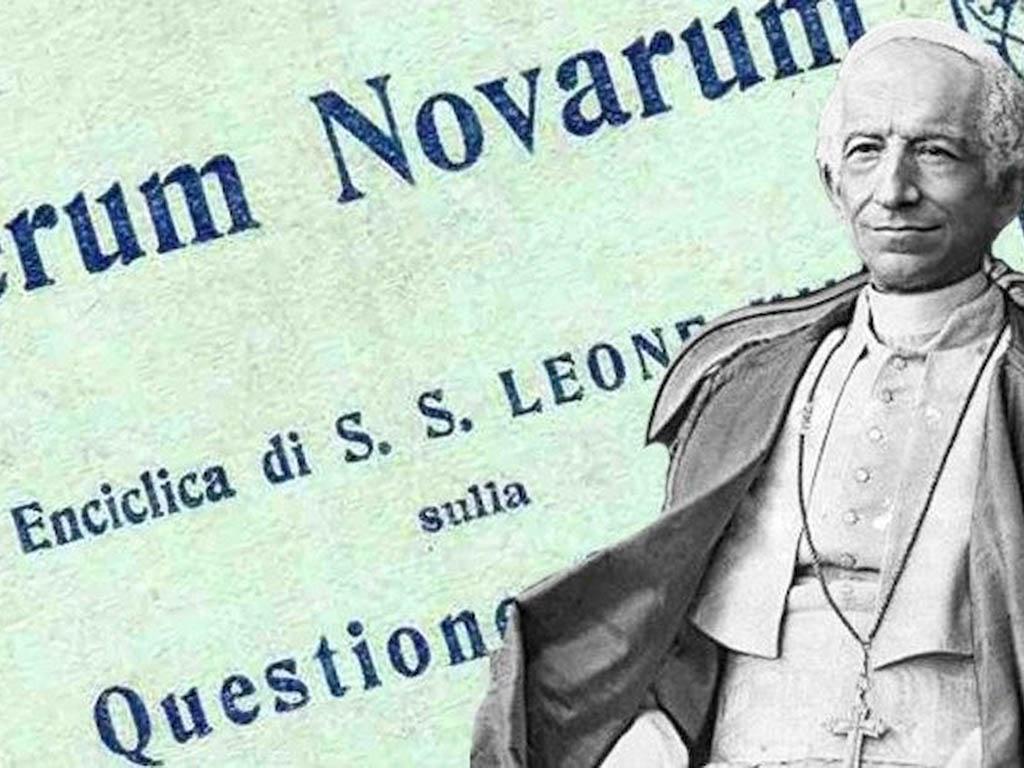

Along those lines, you argue that although education is now secular, the transition was flawed because we abandoned moral education capable of distinguishing right from wrong without religious criteria.

Yes, because religion used to do that—but tied to a religious doctrine. That connection created believers whose behaviour was guided by moral teaching.

Religion achieved this because the very concept of religio implies binding people together, maintaining a community that knows what it must do based on shared convictions that produce moral conduct.

With the secularization of society, nothing has replaced what religion once did to connect people through a moral sense. We haven’t found a way to cultivate moral sensibility, and that’s a real problem.

To give a concrete example, in our case we moved from a national-Catholic, Francoist dictatorship to a democratic regime. We believed that by establishing democratic institutions, we would automatically become democrats—that people would change their mindset.

This happened only partially and not satisfactorily, in the sense of creating a community aware of society’s flaws and challenges and committed to correcting them together.

So, almost fifty years after Franco’s death, have we failed to build a truly democratic demos?

It is a liberal demos, but based on a very reductionist and simplistic concept of freedom—one shaped mainly by consumer economics rather than by ethical motivation.

Victoria Camps © Espacio Fundación Telefónica / Javier Arias

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment