Synodality and ecumenism: a necessary link

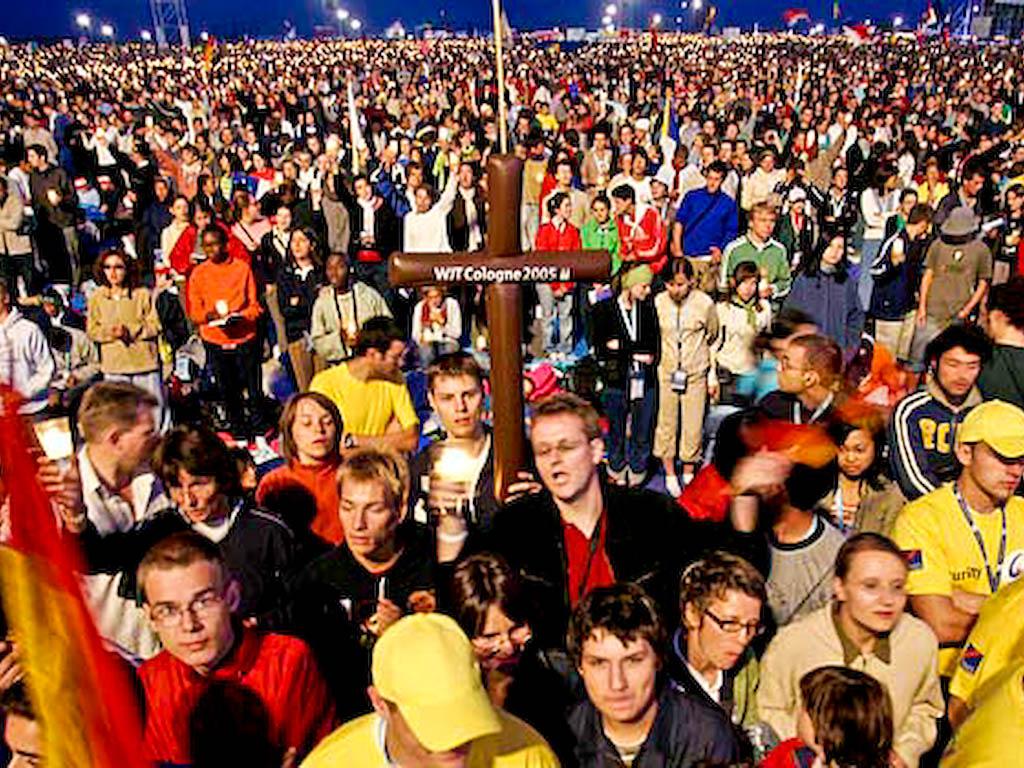

Dicastero per la promozione dell’unità dei cristiani 18.01.2023 Kurt Koch Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgEmbarking on and deepening the path of synodality is what "God expects from the Church of the third millennium". Pope Francis recalled this important goal on the occasion of the 50th anniversary commemoration of the Bishops’ Synod and also expressed his conviction that the commitment to build a synodal Church is "fraught with ecumenical implications".

It is therefore useful to reflect on the close link between synodality and ecumenism: synodality has an ecumenical dimension and ecumenism needs to be realised in a synodal manner. The close link between synodality and ecumenism is already clear from the fact that synodality is an important topic on the agenda in all ecumenical dialogues aimed at restoring Christian unity. This is even truer in the ecumenical dialogue with the Orthodox Churches, which has long been devoted to the relationship between synodality and primacy.

The synodal dimension of Church life, however, plays a significant role not only in ecumenical dialogues. And the ecumenical dimension of synodality is a useful path on which the synodal process in the universal Church can make progress. This dimension is explicitly indicated in the Synod Vademecum: "Dialogue between Christians of different denominations, united by a single baptism, occupies a special place in the synodal journey" (n. 5.3.7). And the Working Document for the continental stage entitled Widen the space of your tent even states: "There is no complete synodality without unity among Christians" (n. 48). It therefore makes sense to question the reasons for this close link between synodality and ecumenism.

Being on the way together

Synodality and ecumenism are inextricably linked to the journey image. The term synodality contains the very concept of journey. The word synod is made up by the Greek terms hodos (path) and syn (with) and expresses the fact that people set out together. In the Christian sense, the word synod designates the common walk of those who believe in Jesus Christ, who revealed and called himself 'the Way' (John 14:6). Originally, the Christian religion was therefore designated as the 'way' and Christians in following Christ were called 'followers of the Way' (Acts 9:2). In this sense, John Chrysostom was already able to state that Church is a name "signifying a common path" and that, therefore, Church and synod are "synonymous". The Church is, in the words of Pope Benedict XVI, a "community of faith on the way".

For the understanding of ecumenism, the idea of journey is also crucial. Ecumenism is the path by which the unity of the Church, lost in history, can be restored. It is no coincidence that John Paul II began the third chapter of his encyclical on ecumenical commitment, Ut unum sint, with the question “Quanta est nobis via? - How far still separates us from that blessed day when full unity in the faith will be achieved and we will be able to concelebrate the Lord's Holy Eucharist in concord"? (n. 77).

Francis places special emphasis on the journeying dimension of ecumenism. For him it is fundamental that different Christians and Church communities walk together towards unity: unity grows as we walk, and walking together already means a living unity. Pope Francis expressed his ecumenical conviction in eloquent words: “Unity will not come as a miracle at the end: unity comes in the journey, the Holy Spirit makes it in the journey.” In order for the quest for unity to remain on the way and thus advance in a synodal manner, all the baptised are invited and obliged to embark on this journey. Ecumenism is a duty for the whole Church, as the Second Vatican Council strongly emphasised in its decree on ecumenism Unitatis redintegratio: "The care of restoring unity concerns the whole Church, both faithful and pastors, and touches each one according to his possibilities, both in everyday Christian life and in theological and historical studies" (no. 5).

Dialogue as a style of synodality and ecumenism

Corresponding to the character of the synodality path is the fact that Pope Francis is not primarily concerned with reviving and deepening synodality through structures and institutions, but intends above all to promote its interior and therefore dialogical dimension, in which the role of the Holy Spirit and his common listening are crucial: "Let us listen, let us discuss as a group, but above all let us pay attention to what the Spirit has to say to us". In light of this synodality characteristic, which is strongly centred on the Holy Spirit, the fundamental distinction between synodality and parliamentarianism, which Pope Francis has repeatedly highlighted, also becomes clear.

While the democratic process primarily serves to determine majorities, synodality is a spiritual event that aims to find a sustainable and convincing unanimity in the faith and lifestyles derived from it, of the individual Christian and the ecclesial community; this presupposes the journey of the spirit’s discernment. Therefore, the synod, in the words of Pope Francis, "is not a parliament, where negotiation, bargaining or compromise are used to reach a consensus or a common agreement. The only method of the synod is to open ourselves to the Holy Spirit, with apostolic courage, with evangelical humility and confident prayer, so that He may guide us.”

The true style of a synodal Church is therefore dialogue. Dialogue as a principle and as a method is not simply a fashion of today’s Church, but represents the essential element of the Church, as Pope Paul VI already observed in his encyclical Ecclesiam suam: "The Church must come into dialogue with the world in which she lives. The Church becomes word; the Church becomes message; the Church becomes conversation" (no. 67).

Pope Paul VI expressed in this way what the Second Vatican Council intended, namely that the Church wants to be in dialogue with everyone: in dialogue with the different states of the faithful’s life and the various vocations within it, in dialogue with other Christian Churches and ecclesial communities, in dialogue with other religions, in dialogue with different worldviews and ethics, in dialogue with the sciences, and in dialogue with the different spheres of people's lives in today's society. Just as dialogue is the style of a truly synodal Church, so ecumenism stands or falls with its dialogical style. In this regard, the decree on ecumenism Unitatis redintegratio emphasises the importance of "each one treating the other as equals" in order to have the interrelationship that is necessary in an authentic ecumenical dialogue, par cum pari agat (no. 9).

Ecumenical dialogue takes place on the basis of the common Christian heritage and is, consequently, a dialogue between baptised brothers and sisters. It is equally evident that ecumenical dialogue in no way questions the interlocutors’ faith identity, but rather presupposes and enhances it. From all this emerges the true core of ecumenical dialogue. It is not merely an exchange of ideas and thoughts but, more fundamentally, an exchange of gifts. For Francis, it is a matter of welcoming what the Holy Spirit has sown in other Churches "as a gift also for us"; it is no coincidence that the Pope, giving an example, mentions that, in dialogue with our Orthodox brothers and sisters, we Catholics have the opportunity "to learn something more about the meaning of episcopal collegiality and their experience of synodality" (Evangelii gaudium, no. 246). This dialogical exchange of gifts takes place in the conviction that no Church is so rich that it does not need to be enriched by the gifts of other Churches, and no Church is so poor that it cannot offer its own contribution to the wider Christendom.

The Synodal Principle and the Hierarchical Principle

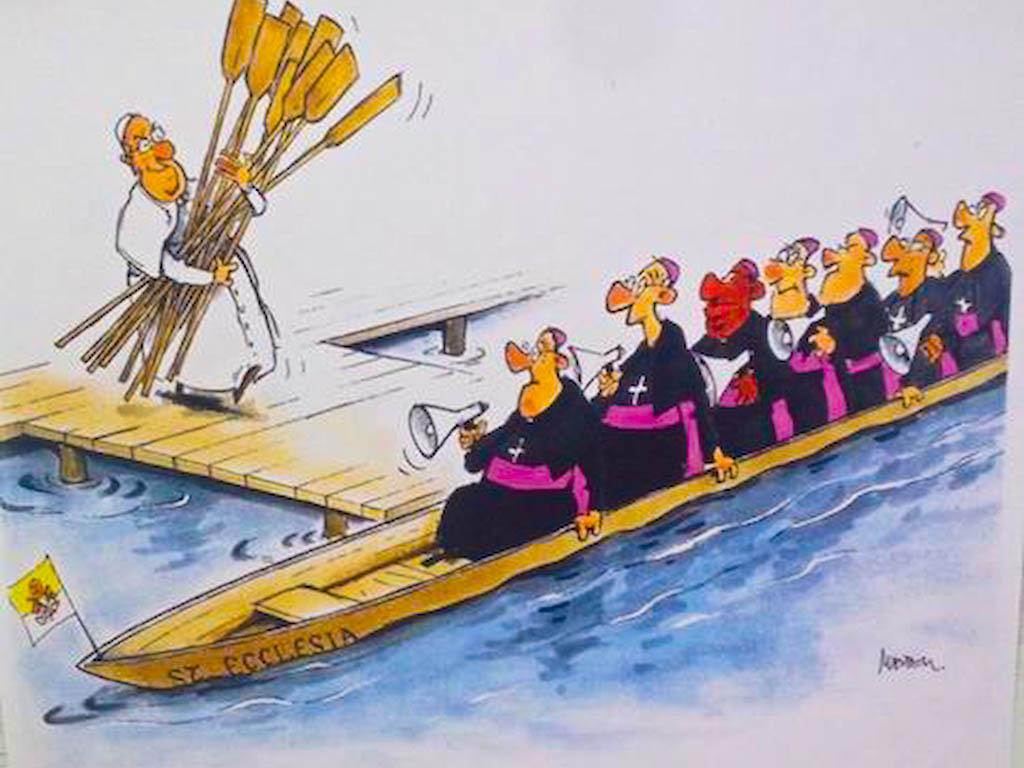

The dialogical style of the Synodal Church would not be properly understood if synodality is opposed to hierarchy in the Church, which in fact is the case in quite a few discussions today. Yet, synodality and hierarchy are inextricably linked. They demand and promote each other. Without hierarchy there can be no synodality, and without synodality the hierarchy cannot act. This is particularly evident if one considers the word 'hierarchy' from an etymological point of view, and thus does not translate it as 'holy lordship' but as 'holy origin'. The mission of the hierarchy in the Church is therefore to protect and pass on the 'holy origin' of the Christ event, so that it can perform its liberating work also in the Church’s present situation.

However, the hierarchy cannot undertake its mission alone; it must walk this path together with all believers, in a synodal manner. Indeed, syn-hodos indicates the common path in the common faith of the Church. From the point of view of Catholic ecclesiology, it is of fundamental importance that synodal and hierarchical principles interact in such a way that the very nature of the Church becomes visible, as expressed by theologian Medard Kehl: “The Catholic Church conceives itself as a sacrament of the communion with God; as such it forms the community of believers gathered by the Holy Spirit, conformed to Jesus Christ the Son and called to enter into the kingdom of God the Father with all creation: a community that is constituted synodally and hierarchically at the same time”. It is crucial to understand how this “at the same time” is to be understood and realised. Pope Francis, in this regard, is not only convinced that synodality, "as a constitutive dimension of the Church, offers us the most adequate interpretative framework for understanding the hierarchical ministry itself", since those who exercise authority in the Church are called "ministers", "according to the original meaning of the word". He is also convinced that "the careful examination of how the principle of synodality and the service of the one who presides are articulated in the life of the Church" can make a significant contribution to ecumenical reconciliation between the Christian Churches. It is therefore understandable that theological and pastoral efforts to build a synodal Church also have rich implications for ecumenism, as it is particularly clear in the dialogue between the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church as a whole.

However, the relationship between synodality and hierarchy needs to be studied and explored further in all ecumenical dialogues, especially since the question of ministry is the real crux of ecumenical discussions. On how to understand the relationship between the synodal life of the Church and the hierarchical ministry in the Church, Cyprian of Carthage, an important African bishop of the early Church, provided clear indications, which can be fruitful even today from an ecumenical point of view: Nihil sine episcopo, nihil sine consilio presbyterii, nihil sine consensu plebis, 'nothing without the bishop, nothing without the presbyters’ council, nothing without the people’s agreement'.

With this eloquent formula, Cyprian not only suggests that the episcopal ministry must be realised and proven in three ways - synodal, collegial and personal - but he also and above all targets those behaviours that must be excluded because they endanger fruitful coexistence in the Church: formation of separatist groups (hence nihil sine episcopo), autocratic bishops who intend to do everything themselves (hence nihil sine consilio presbyterii) and various types of clericalism (hence nihil sine consensu plebis).

From an ecumenical point of view, we must first of all orient ourselves together, once again, towards the Apostolic Council, in which the paradigmatic archetype of synodal assemblies can be recognised. In this regard, we are told that after detailed discussions in the Jerusalem community and after hearing the authoritative testimony and creed of Peter, the decision was made by James, head of the Jerusalem church, in these terms: "It was decided, by the Holy Spirit and us" (Acts 15:28). The important matter was decided by James with the power of the Holy Spirit; then this decision was accepted by the Jerusalem’s entire assembly and later also by the assembly in Antioch.

The spiritual deepening of synodality

The clear distinction between the reflection process aimed at decision-making, in which all the baptised must participate as far as possible in accordance with the principle already widespread in the early Church that what concerns all must also find the consensus of all (Quod omnes tangit, ab omnibus tractari debet), and the decision-taking process that is the responsibility of the ecclesiastical authority, can only take place if one deepens through a spiritual way in what is the essence of synodality.

The nascent Church gave itself the name ekklesia. In secular Greek terminology, this word referred to the popular assembly of a political community, but in the language of faith it means the community of the gathered believers. The latter community differs from the former mainly in the fact that in the Greek polis, people gathered to make important decisions, whereas the community of faith gathered not to decide by itself but to listen to what God had decided, to give its consent to it and to translate it into everyday life.

One understands then why the word ekklesia denotes Christian worship and thus the gathering of the faith community summoned to celebrate the Eucharist. The deepest essence of the Church as synod is the Eucharistic assembly. The Church as synod lives above all where Christians gather to celebrate the Eucharist, as the International Theological Commission emphasises: "The synodal journey of the Church is configured and nourished by the Eucharist". The fact that the origin and summit of synodality lie in the conscious and active participation in the Eucharistic assembly is still expressed today in the custom of initiating synodal assemblies, such as councils or synods of bishops, with the celebration of the Eucharist and the enthronement of the Gospel, as already prescribed from the Councils of Toledo in the 7th century until the Ceremoniale Episcoporum of 1984. Since the Church's synodality always needs spiritual deepening, it can learn much from the ecumenical movement, and in particular from spiritual ecumenism, defined by the Second Vatican Council's Decree on Ecumenism as "the soul of the whole ecumenical movement" (no. 8).

Prayer for Christian unity is in fact the basic form of ecumenism in which everyone can participate synodically. Through prayer, we Christians express our conviction of faith that we human beings cannot forge unity on our own, or even decide its form and timing. Rather, we are inclined to producing divisions, as past and present history shows. We can only receive unity from the Holy Spirit, who is the divine source and engine of unity. Just as spiritual ecumenism is the spiritual foundation of the all ecumenical movement, so too the synod process always requires spiritual deepening, in which prayer plays a guiding and accompanying role. Also and especially in the perspective of ecumenical commitment, it is significant that synodality, even before the different structures and institutions, has an underlying spiritual dimension, in which the role of the Holy Spirit and his common listening are crucial.

This aspect was highlighted by the international ecumenical symposia entitled “Listening to the East”, which addressed concepts and experiences of synodality in the Eastern Orthodox Churches and the Oriental Orthodox Churches. These symposia made it clear once again that the Catholic Church can learn much from the experiences of other Christian Churches in the effort to build a synodal Church. But they showed at the same time that the deepening of the synodal dimension in theology and praxis in the Catholic Church is an important contribution the Catholic Church must make to ecumenical dialogues, also and above all with a view to a better understanding of theology and the exercise of the Petrine ministry, which, in Pope Francis' conviction, will be able to receive greater light in a synodal Church: "The Pope does not stand, alone, above the Church; but within it as a baptised person among the baptised and within the College of Bishops as a bishop among the bishops, called at the same time - as successor of the Apostle Peter - to lead the Church of Rome which presides in love over all the Churches."

This shows how much the theology of synodality and ecumenism can learn from each other, accompanying the Church and the cause of unity towards a fruitful future. Synodality and ecumenism remain in close interdependence, and together they assist the credible mission of Christianity in today's world.

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment