The decline of the Batwa

Mundo Negro 01.10.2019 Carlos Micó Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgUganda: protection of mountain gorillas threatens pygmies. The fight to save mountain gorillas from extinction is the story of how a bad approach to the conservation of nature can lead to the violation of human rights and the destruction of lives such as that of the Twa Pygmies who, expelled from the jungles that were their home, face the imminent disappearance of their culture (Translation from Spanish by Alissa D’Vale).

Although the animal that appears in the Ugandan flag is the crowned crane and it flanks the country’s coat of arms in the company of the kobo antelope, the true national emblem are the mountain gorillas. Indeed, these great primates are the main tourist attraction of the so-called Pearl of Africa. Their image takes over Entebbe airport, appears on 50,000 shillings bills and even on entry visas to the country. Each year they attract thousands of visitors, who pay between $450 and $600 for the opportunity to spend an hour with them in the Impenetrable Forest National Parks of Buindi and Mhahinga.

These animals drew the attention of public opinion as a result of the work that the American Dian Fossey carried out in the Volcanoes National Park, between 1966 and 1985, in the neighboring country of Rwanda. At that time, the species was, with 240 specimens, on the brink of extinction. About half of these animals lived in the mountains of southwestern Uganda. For this reason, in 1991 – under the auspices of the Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA) and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) – the Mhahinga and Bindi National Parks were founded, joining the Congolese Virunga National Park and the Volcanoes National Park in Rwanda, both founded in 1925.

In 1994, given the rich biodiversity and strategic importance of these peaks for gorilla conservation, Buindi was included in UNESCO’s world heritage list. As a result of conservation efforts and strict government policies, the mountain gorilla population has recently surpassed the 1,000 mark, changing the status of “critically threatened” to “endangered,” according to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. A success that, in parallel, has boosted the economic development of the Kabale, Kisoro and Rukungiri districts in the depressed area of southwestern Uganda – eight dollars from each national park access permit goes to local communities. But, with the protection of the gorillas, the beginning of the end came for around 3,000 and 7,000 Twa Pygmies who were estimated to inhabit the jungle, in perfect harmony with the gorillas and the rest of the ecosystem.

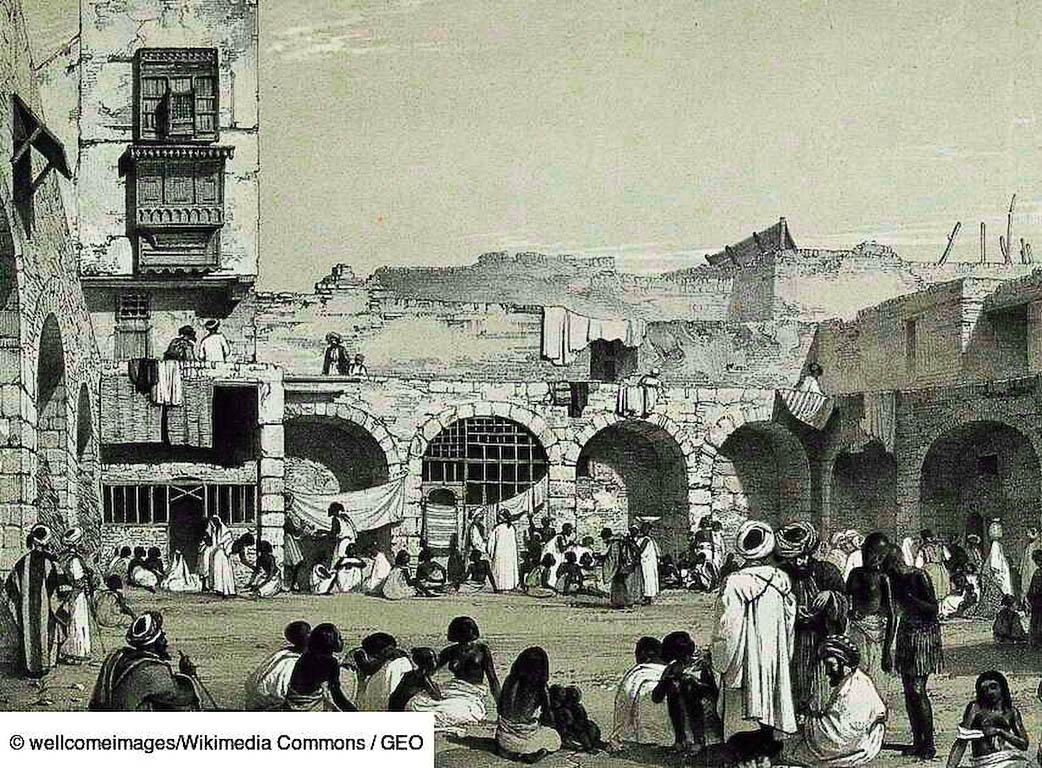

During the creation of the parks, the UWA proceeded to evict the pygmy people, sometimes violently. Ripped from the jungle, their world fell apart. Practically overnight, they were banned from their home. Since then, neither the Ugandan government nor the UWA have allowed them access to the benefits derived from ecotourism. Nor have they offered any compensation for the expulsion from their territories. By losing their land, the Batwa also lost their voice. Thus, these ancient nomads were forced to settle on the edges of parks and on the edges of roads, where filthy shacks replaced the traditional mogulus – small cabins built with interlacing branches and leaves.

A difficult adjustment

Forced settlement and the transition to a productive money-based economy is not easy for the Pygmies, who have a hunter-gatherer culture. They are trapped between two worlds: the jungle, to which they cannot return, and the Bantu world, which does not accept them. A clear example of this difficult adjustment is the incident that took place in February 2017. A 72-year-old Batwa, Kafukuzi Valence, was arrested for hunting a small antelope inside the Buindi National Park, something that before the expulsion, was part of his routine. Accused of smuggling, he was imprisoned for seven months, also with a fine of 5.7 million Ugandan shillings – about 1,500 euros – was imposed, a sum that is impossible to raise for a community that is deprived of resources.

But, in addition, the relationship with their Bantu neighbors does not help. Traditionally, the Pygmies, throughout their presence on the continent – connecting the equatorial rainforest of central Africa, from Cameroon and Gabon, to Rwanda and Uganda, via the two Congos and the Central African Republic – have been viewed by the Bantu as primitive and inferior beings. The very term pygmy is used with a derogatory spirit on many occasions. The Batwa live subjected to them, with no other option than to carry out agricultural tasks that they did not need in the jungle and that are totally unknown to them. For a day of work in the service of the local owners, a Twa barely receives the equivalent of one euro. Other times, the payment consists of meager amounts of food. Occasionally, some Batwa have the opportunity to earn a little extra money by performing at attractions such as the Batwa Experience, or the Batwa Trail, theatrical shows for which tourists pay between $80 and $100 to see scripted and unrealistic performances of the culture of pygmies of the African jungle.

Marginalization starts from childhood. The Bantu often refuse to allow their children to share schools with Pygmy children. Schools from which, on the other hand, the little Batwa often run away. When you hardly have anything to eat, studying becomes difficult indeed.

An uncomfortable truth

On trips to Uganda, Buindi was an unavoidable stop, its gorillas were the highlight of this route. We tried to directly contact the Batwa that survived in the communities surrounding the national park. It was impossible. There was always an intermediary, either UWA agents or a landowner, who kindly offered to introduce us to “his pygmies.” Once brought before them, all of them would warn us that no one Pygmy spoke English and that, therefore, they would act as translators. Obviously, at their convenience.

–What you want to know, ask me. They don’t understand you – said Moses, the UWA agent who was accompanying us.

I wanted to know first-hand the official position of the UWA. So, pretending not to know the story, I asked:

–You have told us that the Batwa lived hunting in the forest. So why are they here outside of it?

–The UWA made them leave to establish the national park and save the last remaining gorillas. If we hadn’t, gorillas would no longer exist. The hunt was killing them.

– The hunt of the pygmies? Did pygmies risk hunting something as large and dangerous as a gorilla when they were able to hunt a duiker, birds, or smaller monkeys?

–The ropes and traps with which they hunted, sometimes caught the hand or the foot of a gorilla. The limb becomes gangrenous, and the animal ends up dying from the infection.

Some Batwa had taught the group that I led that they made their traps with vegetable fibers. Then they started screaming and jumping, pretending to sing and dance ancient jungle songs. Others remained silent, fixing their submissive gaze on the ground. The debate with Moses continued. As a UWA member, he was very confident and proud of what he was saying. I insisted.

– But Moses, those traps were made with vegetables, they just taught us. A gorilla can easily break those ties with his hands or teeth.

–Yes, but the problem is that Bantu hunters joined the Twa hunting parties who brought metal ropes and stocks. Those are the ones that killed gorillas.

Obviously, all these arguments were just excuses. It is unlikely that the Batwa’ wood and vegetable traps posed a danger to the survival of the last gorillas. Similarly, it is hard to believe in this high incidence of metal stocks used by Bantu hunters. In West Africa, these hunting methods, used to obtain meat from wild animals, the so-called ‘bush meat’, do pose a real conservation problem. But in Uganda, where the land is fertile and food is not in short supply, it is unlikely that this practice was responsible for putting gorillas on the brink of extinction, as the UWA claims.

The main problem for the survival of mountain gorillas has always been poaching, which in no case uses lassoes and traps, but rather more active methods such as machetes and firearms. Therefore, under the pretext of fighting against poaching, the Ugandan Government and the UWA kicked out the Batwa, not because they posed a danger to the gorillas, but because of the need to control them, even if they were not recognized as citizens. On the other hand, their non-productive way of life is seen as a primitivism that does not interest the Government of Uganda, which aims to offer the world an image of modernity, development, and a firm commitment to conservation.

– We have restored the jungle. Now it is as before the Pygmies came to it. It belongs entirely to the animals, Moses said with a satisfied smile.

This last argument is especially dubious when it is seen that, within other important Ugandan national parks such as the Queen Elizabeth, also managed by the UWA, there are human settlements whose impact on fauna and the landscape is undoubtedly much greater than that of the Pygmies have in the jungles where they were born. It is sad to see how something positive, the conservation of nature and endangered species, leads to the destruction some of the last primitive peoples of the planet. It is no exaggeration to say that, for the Ugandan Government and UWA, the life of a gorilla has more value than that of a Twa.

Organize or die

In light of institutional abandonment, the marginalization and social dependence to which this town is subjected, their hopes remain in the hands of NGOs, most of them foreign and religious in nature, although in 2000, in Kisoro, the United Organization for Twa Development in Uganda (UOBDU) was founded – the only organization created by the Batwa themselves to claim their rights.

The main objective of these organizations is to provide the people of the jungle with arable land and seeds to learn to practice subsistence agriculture that reduces dependency on their neighbors. The unsanitary conditions in the shanty towns where they live means that, according to data from the Batwa Development Program, 38% of Twa children die before reaching the age of five. For the rest of Ugandan children, this rate is 18%. Therefore, housing improvements are also considered a priority. Finally, introducing literacy implies the main way to claim their rights, and thus, equate themselves with the rest of Ugandans.

– There is no life for us. Neither inside the forest nor outside it – laments Alice Nyamihanda, a prominent member of UOBDU and the first Twa to graduate from university.

Despite this growing organization, Pygmies’ demands do not include a return to the jungle. The elderly have assumed that they will not be able to return, and the first generation of Batwa born outside the forest are in an identity limbo. Their aspirations are not so much to return to the home of their ancestors, but to be recognized as citizens and have the same rights as the rest of the population, even if this means definitively renouncing their ancient tradition. With lost pride in their culture, without being blamed for it, we can foresee that sadly, in the coming decades, we will witness the extinction of the culture of Uganda’s last hunter-gatherers.

After all, being Batwa has brought them nothing but pain.

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment