The True Face of Voodoo

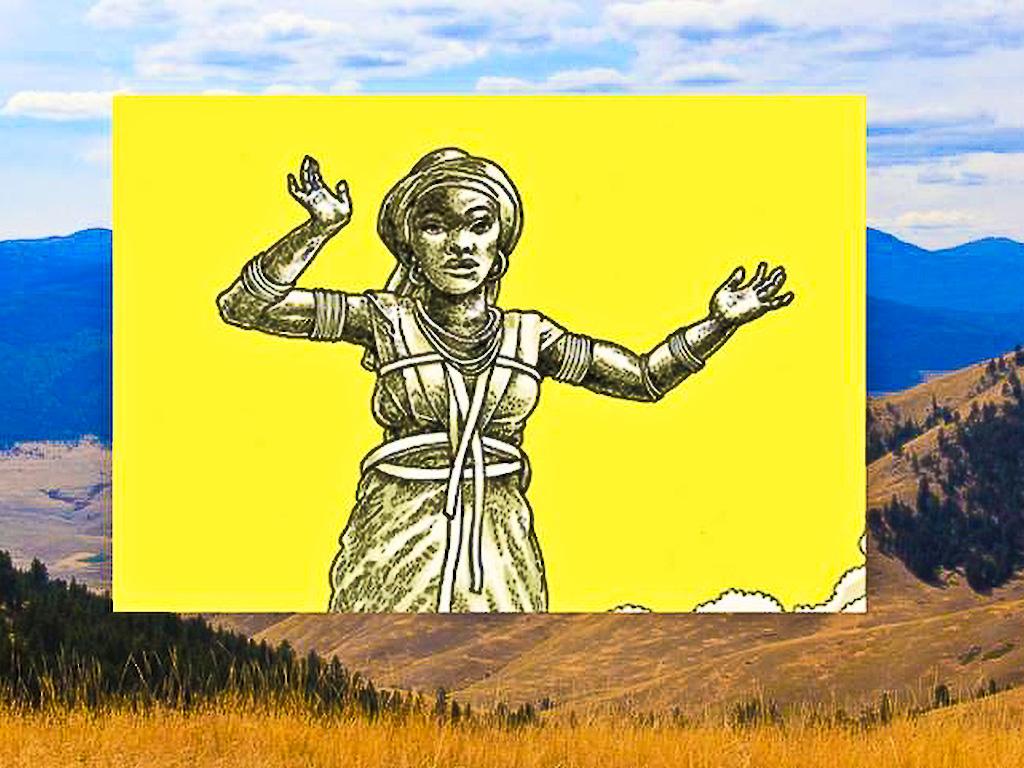

Rivista Africa 20.09.2025 Marco Aime Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgOften misunderstood and reduced to dolls and dark magic, Voodoo is actually an ancient African religion with deep spiritual roots. Born in southern Benin, it is based on a covenant between human beings and the divine, expressed through drum rhythms and dance. It is a journey through ritual possessions, sacred symbols, and the memories of Africa’s deepest soul.

When people hear the word Voodoo, strange thoughts often come to mind. It immediately evokes, for most, images of dolls and figurines pierced with long needles to hurt, even from a distance, a hated person. Yet beyond this false image—nurtured by too many Hollywood horror films—what does this cult truly represent?

The term derives from the Fon language, spoken in southern Benin, and originally meant “spirit” or “protective genius.” From the coasts of the Gulf of Guinea, this ancient faith crossed the ocean on slave ships and reached Haiti, where it flourished perhaps even more than in its homeland. Though it absorbed local and foreign influences that brought certain changes, Voodoo has retained its essential traits, and its roots still lie deep in the fertile soil of African cultural tradition.

As the ritual of possession par excellence, Voodoo has long been dismissed as a phenomenon of collective trance. However, more recent studies have acknowledged its theological depth and recognised it as a true religion.

In precolonial African societies, Voodoo brotherhoods played a crucial role in preserving local authority. They functioned as highly structured institutions integrated into the political fabric, helping to legitimise the power of traditional chiefs. Followers of the cult are consecrated to a deity and serve it through these institutions. They do not choose to be possessed—they are chosen.

Behind the spectacular aspect of Voodoo, seen during feasts and initiation ceremonies, lies a firm covenant between humans and the gods: a mutual exchange in which humans offer prayers and gifts, and the deity responds with its presence and protection. It is precisely this ceremonial side that has made Voodoo famous and attracted the interest of many scholars.

At its core lies rhythm—the obsessive rhythm of drums accompanying the ceremonies. Each particular beat represents the name of a spirit, a sign that its presence is near, and every participant must surrender to the rhythm of the spirit that will possess them. This trance reflects a local concept of rhythm as movement in action. Dance thus becomes the path to a state of serene ecstasy marking the spirit’s arrival.

The loa, or spirit, may appear in different forms: Agwé, lord of the seas symbolised by a fish; Ogun, god of iron and fire; or Damballa, the serpent god of fertility. The possessed person imitates the traits of the spirit—sometimes gentle, sometimes violent—depending on which loa dominates. The bond between loa and possessed is compared to that between a rider and his horse: it is said that the loa “rides” the possessed.

Possession by the loa reflects the three classical stages of a rite of passage: separation from the former state, represented by trance; transition, expressed through ritual scenes where the possessed act in semi-consciousness; and reintegration, marked by awakening from trance. In the first stage, the possessed exhibits violent gestures, screams, and trembling. Once the loa “mounts its horse,” the possessed follows its spirit’s nature—ferocious or gentle, mimicking its movements. In the final stage, the person emerges from trance, overwhelmed by exhaustion, and falls into deep sleep.

Upon awakening, the initiate becomes a member of the brotherhood and joins community life, often finding renewed social belonging that makes their existence more fulfilling.

Friends in Benin have told me that in recent years, members of some of the many religious sects proliferating across Africa travel through villages buying Voodoo ritual objects and figurines at very high prices in order to destroy them. Priests often sell them and continue their ceremonies peacefully using other, newer objects. This iconoclastic frenzy, absurd as it may be, has paradoxically identified evil within the objects themselves. In truth, it is the very materiality of these objects that forms the basis of the cult, while creating a complex relationship between the divine and its material representation.

Photo of Eric Lafforgue

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment