Restoring Memory: Africa and Cultural Justice

Rivista Africa 30.05.2025 Valentina Giulia Milani Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgFrom Nigeria to Mozambique, a growing movement across the African continent is calling for the return of artworks looted during colonialism. This is part of a broader cultural decolonization process that is restoring voice and dignity to African peoples.

The demand for the return of artworks and cultural property looted during colonial times is emerging as one of the main claims for historical justice by many African states. From Nigeria to Mozambique, from Gabon to Senegal, an increasing number of nations are resolutely demanding the return of their artefacts—often sacred ones—which have remained for decades far from their places of origin, displayed in major European museums.

The latest country to take this step is Mozambique. Less than a month before the 50th anniversary of its independence, the Ministry of Culture has launched a national inventory of artworks taken during Portuguese rule. “We are rebuilding our collective memory,” said Education and Culture Minister Samira Tovela. Mozambican authorities estimate that at least 800 art and religious objects were dispersed, some of which are currently held in public and private collections in Portugal and other European countries.

In Gabon, recent developments mark a more concrete step toward reclaiming cultural heritage: on Wednesday, during an official ceremony presided over by Vice-President Séraphin Moundounga, 91 historic items—including masks, statues and ritual objects from various local communities—were returned. The event, held at the National Museum of Arts, Rites and Traditions of Gabon, was highly symbolic and culturally significant. Among the returned items were Tsogho statues, and Fang, Téke, Punu and Myènè masks.

Perhaps the most symbolic case remains that of the Kingdom of Dahomey, corresponding to present-day Benin,—not to be confused with the historic Kingdom of Benin, which existed in present-day Nigeria and is remembered today in Edo State and its capital, Benin City. In November 2021, France returned 26 works of art belonging to the royal treasure of Abomey, looted in 1892 by French colonial troops during the conquest of the Kingdom. These included thrones, statues, and royal sceptres—symbols of power and spirituality. Initially, the items were displayed in the ceremonial hall of the presidential palace in Cotonou, attracting over 230,000 visitors between February and August 2022.

This restitution process was completed in May, when Finland returned a kataklé, a ceremonial stool used in royal coronations, completing the repatriation of all 27 items from the royal treasure.

Nigeria is also playing a leading role. The famous Benin Bronzes, artistic masterpieces looted in 1897 by British troops during the destruction of the Royal Palace in Benin City, have been returned by several countries. In December 2022, Germany officially handed back 21 bronzes, followed by the Netherlands in February 2025 with the return of another 119 items. Some British institutions have begun restitution processes, but the British Museum continues to retain many artefacts, citing legal constraints.

Ethiopia, for its part, has been demanding for decades the return of objects taken in 1868 following the Battle of Maqdala, when British troops looted the imperial citadel. Among them are tabot—sacred tablets of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church—which are so venerated that they may not be touched or displayed. One was returned in September 2023 during a ceremony in London, but many remain in British museums, despite mounting pressure from Addis Ababa.

Senegal has also formally requested that France return its cultural heritage held in Parisian museums, particularly the Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac. The request concerns hundreds of traditional items—including ritual masks, statues, ceremonial drums, and sacred objects—taken during the colonial period from ethnic groups such as the Wolof, Serer, Diola and Peul. In November 2021, Senegal established a Special Commission for the Restitution of Senegalese Art Collections held in Western museums, based at the Museum of Black Civilizations in Dakar.

Last but not least, Egypt. The Egyptian government has stepped up diplomatic and legal efforts to secure the return of thousands of archaeological items, including statues, sarcophagi, papyri and architectural fragments. One of the most well-known cases is the Rosetta Stone, held at the British Museum, whose return has been sought for years as a symbol of national identity. The Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities has created a permanent committee to monitor illegal trafficking and coordinate repatriation campaigns. In recent years, more than 29,000 items have been recovered from countries including the United States, the United Kingdom, Italy, France and Germany.

Egyptian authorities emphasize that the return of these items is not only an act of cultural sovereignty, but also a key step in reaffirming the historical continuity of Pharaonic civilization as an integral part of modern national identity.

Behind this push for restitution lies a broader trend. The return of cultural items is not only a matter of cultural justice, but also a growing anti-colonial sentiment that, in some regions, has translated into radical political shifts, including military coups. Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger—just to name three recent examples—have seen the rise of military juntas calling for a break with France and a repositioning of national sovereignty, not only in foreign policy but also in terms of historical identity.

However, many challenges remain. Some European museums resist large-scale restitution, arguing that the objects are better preserved and displayed in the host countries, or that they were acquired legitimately. Moreover, the return of artefacts raises questions about their preservation and protection in countries of origin, where museum infrastructure and technical expertise may be lacking. Yet such objections risk perpetuating a paternalistic and colonial logic, ignoring the increasing capacity of African nations to manage their own heritage.

According to UNESCO, more than 200,000 African cultural objects are currently held in museums and private collections outside the continent. The organization has encouraged multilateral cooperation to support repatriation but has not imposed binding mechanisms. In this legal vacuum, African countries are now turning to cultural diplomacy, leveraging media attention and rising global awareness.

It is no coincidence that this year’s theme of the African Union is: “Justice for Africans and people of African descent through reparations.” Proclaimed at the 37th Assembly of the continental organization, the theme highlights the urgency of addressing historical injustices linked to slavery, colonialism, and cultural dispossession.

The return of looted artefacts is thus a vital battleground in the ongoing process of decolonization. It is not just about “repairing” historical theft, but about restoring the African voice in telling its own story. A struggle not waged in museum storage rooms, but in the hearts of a generation determined to rewrite its history and shape its destiny, starting from what was taken away.

See, Restituire la memoria: l’Africa e la giustizia culturale

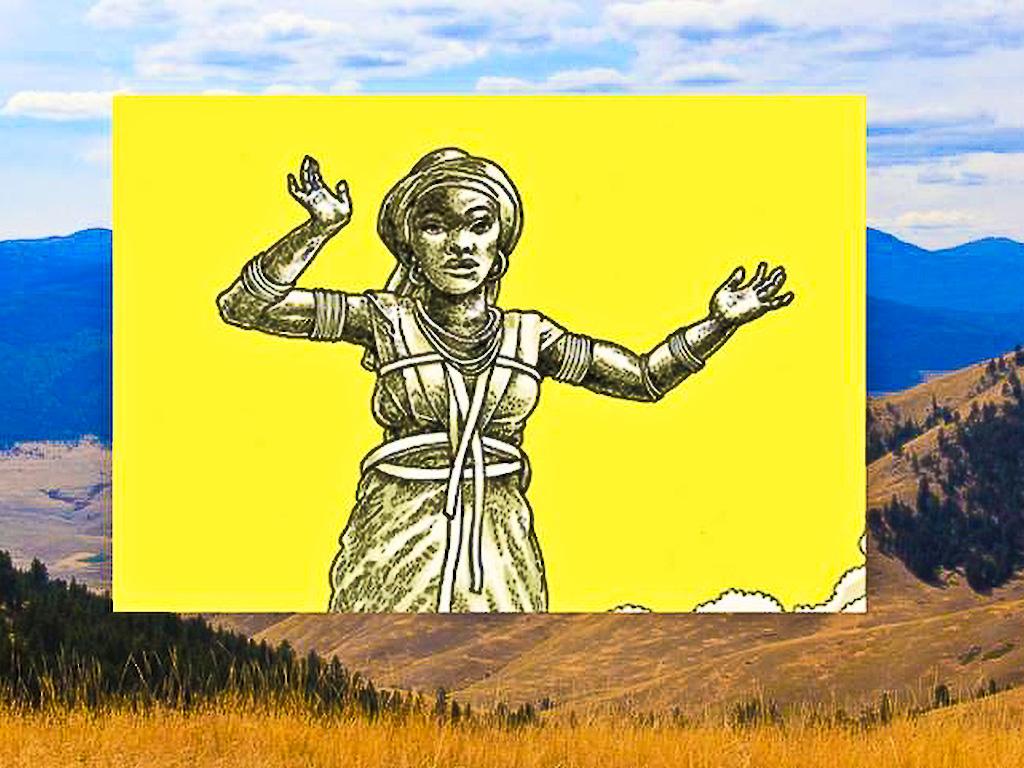

Photo. After a century in exile, the “talking drum” (seen here during a desacralization ritual in November 2022 at the Quai Branly Museum) is being returned to Côte d’Ivoire. Courtesy of Silvie Memel Kassi

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment