The World at War

Ethic 01.02.2025 Manuel Arias Maldonado Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgThe pacifying hopes of Enlightenment philosophy have been thwarted time and again. After the bloody 20th century, the continuity of armed conflicts is particularly disheartening. After burying millions of dead, one would expect our species to have gained a bit more wisdom. And yet, we continue to witness the sad recurrence of war.

There has never been a humanity unfamiliar with war; which means that there has never been a moment in world history free of armed conflict: somewhere on the globe, there are always groups killing one another. Even if we accept Steven Pinker’s thesis that human interactions have steadily become less violent, the raw fact remains that war has not vanished from our horizon. Not even in Europe: Russia’s incursion into Ukrainian territory and the subsequent armed conflict have brought back the sound of bullets whistling in our own backyard. And we ask ourselves, alarmed: how is this still possible?

Yet there is no need to go back to the first half of the 20th century — with two devastating world wars beginning on European soil — to find a precedent: the violent disintegration of Yugoslavia involved atrocious episodes, and Western powers had to send bombers to end the conflict. Both the Balkan wars and the Rwandan genocide served as a warning to contemporaries about the limits of post-communist peace; shortly afterward, Islamic terrorists brought down the Twin Towers. If history had ended, as Fukuyama announced in an often-misread argument about the superiority of democracy, it had a very strange way of doing so.

What stands out in the Ukraine war is the unexpected return of one sovereign state’s aggression (albeit undemocratic) against another (more or less democratic). According to the typology proposed four centuries ago by philosopher Thomas Hobbes, dictator Putin has launched a war of doctrine (nationalist), which is also a war of acquisition (of territory and resources).

This kind of conflict is something Europeans born after 1950 had grown unaccustomed to. It also matches the traditional definition of war — as articulated in the classic study by Hedley Bull — as organized violence between political entities. This form of warfare has become less prominent since the end of World War II and has always been rare between democratic regimes.

Still, we would fall prey to a dangerous optical illusion if we believed that classical war is the only kind possible; even Clausewitz noted that every era has its variants. And ours is not dominated by state action; if we stick to that definition, we would struggle to find actual wars.

But didn’t the Islamic State wage a holy war against the world? Isn’t there a war between Hamas and Israel? Isn’t Sudan in a state of war? And aren’t terrorist groups — even if less active than in the 1960s and 70s — still waging war in various parts of the world for different reasons? Just like the humans who declare or endure them, wars come in a thousand forms.

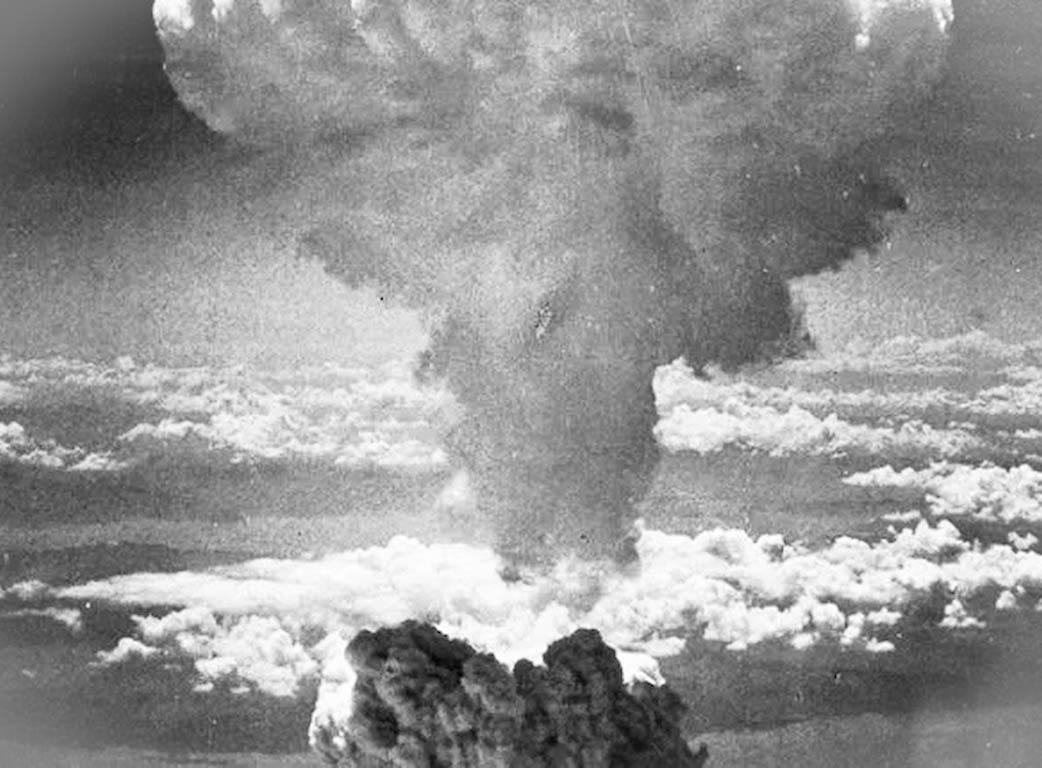

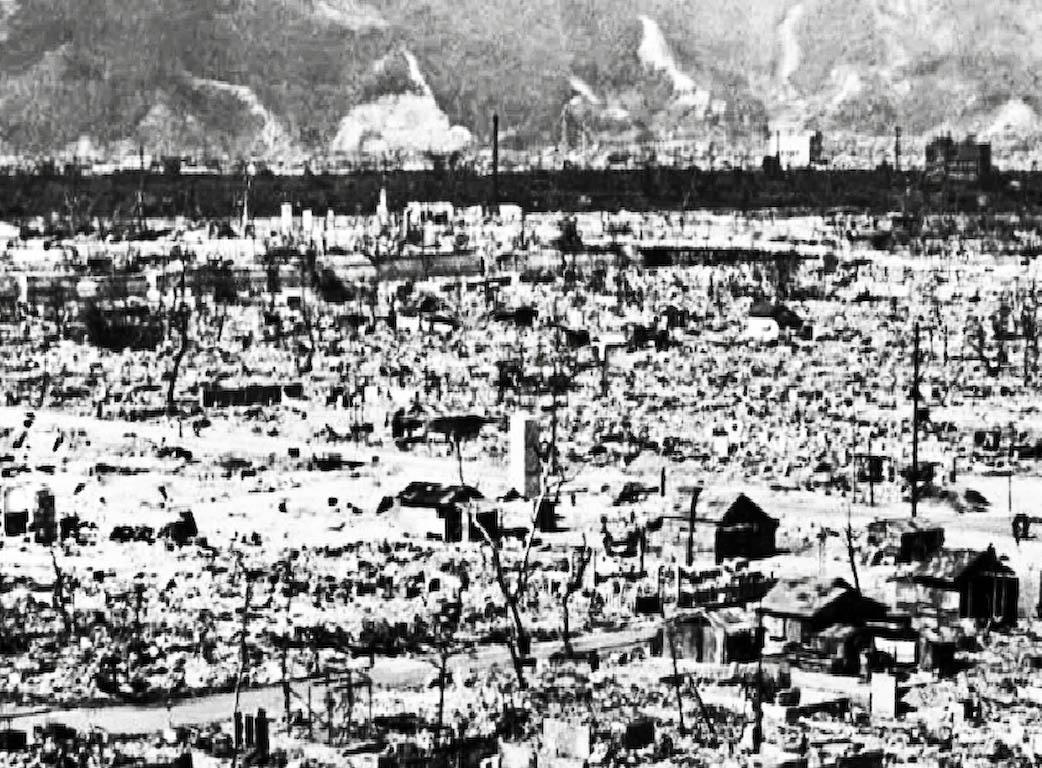

And yet, the question remains: why do wars continue to exist? This question becomes even more pressing after the savage 20th century, which began with a Great War that claimed 37 million lives and was followed by another world war that cost 60 million more — including the extermination of European Jews and the detonation of two atomic bombs on Japanese soil.

“I had not thought death had undone so many,” wrote T. S. Eliot in The Waste Land in 1922, in reference to what was then seen as the apotheosis of militarism. And while novelist H. G. Wells predicted that the Great War would end all wars, it was British Prime Minister David Lloyd George who got it right when he quipped — during the 1919 Paris Peace Conference — that “this war, like the next one, is a war to end war.”

Barely twenty years later, Europe was in flames again and the Japanese Empire was preparing to attack American soil: the pedagogy of horror had failed. It wasn’t the first time; it wouldn’t be the last.

Those European trenches were the real grave of Enlightenment hopes; or, if you prefer, they marked the abrupt end of the 19th century’s boundless faith in the perfectibility of our species. In contrast to the caution found in the writings of Kant, Montesquieu or Hume — all of whom understood how arduous humanity’s path would be — 19th-century hyper-rationalism went too far, or too fast: Europeans believed they had a sacred mission to civilize the savages, and that one day everyone would speak Esperanto. Religion of humanity! For Hegel, war itself could be a civilizing force: “The periods of happiness,” he wrote — to the scandal of Rafael Sánchez Ferlosio — “are blank pages in the book of history”. That’s why he saw, in Napoleon entering Jena triumphantly in 1806, nothing less than the embodiment of the spirit on horseback: a ruler who dealt out both sword blows and civil codes. Across the world, nationalists rose up against the empires that oppressed them or the metropoles that colonized them. Sadly, for moralist compilers, some of these leaders were right; sometimes, armed resistance is the only way to free oneself from a tyrant. And as democracies themselves know, politics — from founding republics to regime change — is often the continuation of war by other means.

This is what we must come to terms with: without fear or hope, on the endless path toward impossible perpetual peace.

It’s doubtful that war will ever leave us; wherever there’s a conflict or an interest in creating one — whether motivated by tribal hatred, resource extraction, or religious and ideological fanaticism — the temptation to resort to organized violence arises. We’ve known since Kant that wars are less likely between democracies; Montesquieu taught us that economic interdependence helps to prevent them. As for the doctrine of just war, experience shows clearly that it’s only just if it’s the only way to stop unjust violence — though its practical application is murky. That’s not much. After burying millions of dead, one would expect more wisdom from our species. But this is what we have to live with: without fear or hope, on the endless road toward impossible perpetual peace.

See, El mundo en guerra

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment