Namibia, the Forgotten Genocide

Rivista Africa 02.10.2025 Annaflavia Merluzzi Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgOn the 2nd October of 1904 began the German colonial genocide against the Herero and Nama communities in Namibia. More than a century later, the wounds remain open: no concrete reparations, a contested official memory, and failed negotiations. The two communities take to the streets to demand truth, land, and justice.

On the 2nd October of 1904, German General Lothar von Trotha, head of the military administration in colonial Namibia, ordered the extermination of the Herero and Nama peoples. That order marked the beginning of the genocide of the indigenous populations, which would only end in 1908, and opened the way for Germany’s experiments in mass killing that would later culminate in the Holocaust.

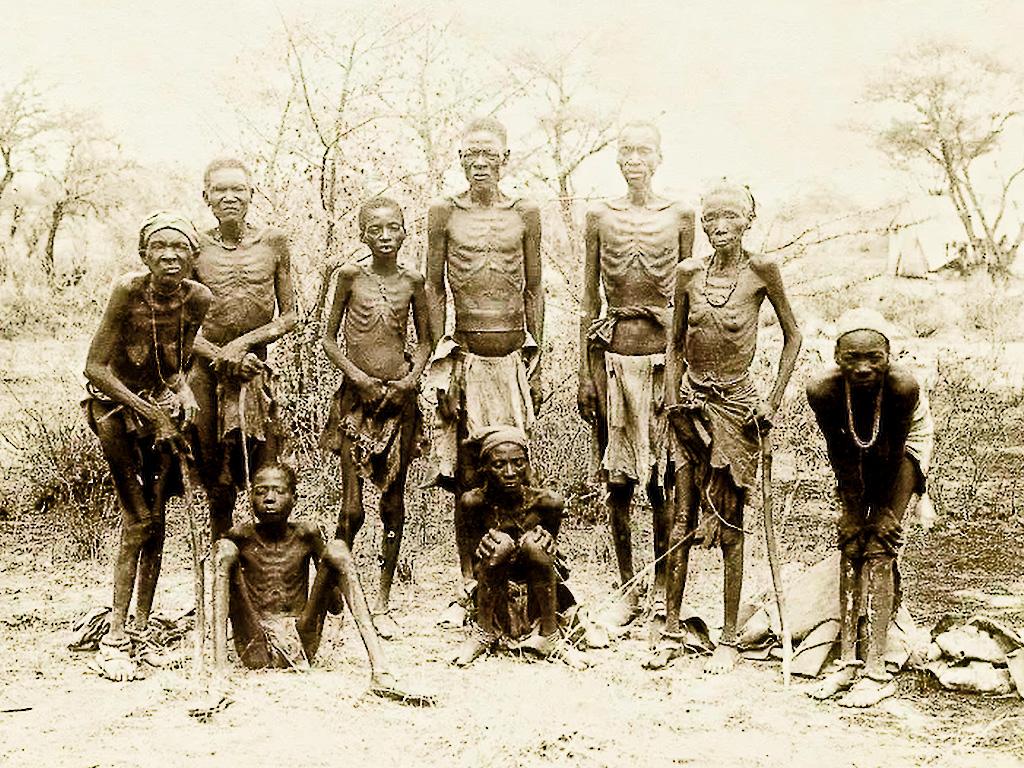

Over those four years, it is estimated that around 80% of the Herero and 50% of the Nama were killed—either directly or through exhaustion caused by forced labour in concentration camps, sexual exploitation, and medical experiments. Hunger, disease, the seizure of livestock, and displacement into the desert areas of the Kalahari completed their destruction.

Today, the two communities have still not received reparations for the atrocities suffered; they remain trapped in social marginalisation, and their appeals continue to go unheard. They now claim the 2nd October as a national day of remembrance.

The creation of an official Memorial Day therefore has a bitter taste, perceived as purely symbolic and disconnected from the real history of the massacre. This year, Namibian President Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah celebrated 28 May as the first official genocide remembrance day, a year after its proclamation. That date marks the closure of the concentration camps in 1907.

In her speech, Nandi-Ndaitwah said: “Those horrific acts are now part of our collective history of resistance and resilience in our march towards freedom,” adding that “our presence on this occasion marks a decisive step in processing the past, through collective remembrance and sharing the pain of the Herero and Nama communities.”

According to Nandi Mazeingo, president of the Ovaherero Genocide Foundation, “this is an attempt to mystify the true history of the anti-colonial struggles courageously fought by the Herero and the Nama, to erase their commitment in defending their lands and livestock when no one else dared to do so.”

The extermination order of 2nd October followed the suppression of liberation uprisings led by the two communities, intended to break their resistance and prevent future revolts. For this reason, rejecting 28 May, Herero and Nama representatives organised an independent commemoration beginning on 1st October and ending on 2nd October, centred on the historical memory of the event.

“We choose 2nd October to commemorate the massacre, even though the memory haunts us every day, as we still live without land, without cattle, in exile, poverty, and marginalisation,”

explained Mazeingo.

The Foundation organised a mass march from Okahandja to the capital Windhoek, passing through symbolic sites of the genocide. Parades, military drills, and ceremonies will stop at the Lutheran Church—considered a “key actor in the execution of the genocide”—where a petition will be handed to the pastor. The same action will be taken at the German Embassy in Windhoek. The day will conclude in front of Namibia’s Parliament, accused of complicity in the delays on reparations and of failing to represent the Ovaherero and Nama peoples.

“We will also pass by the Independence Museum and schools to educate our nation and the world about our history, still excluded from school curricula and public narratives. There, our supreme chief, Mutjinde Ktjiua, will deliver a speech to the media,” added Mazeingo.

The internal tensions follow years of negotiations between the Namibian and German governments, from which the Herero and Nama have always complained of being excluded. In 2021, after eight years of diplomatic mediation, Berlin proposed an agreement worth €1.1 billion to be disbursed over thirty years in the form of funding for infrastructure, vocational training, water supply, and land reform projects.

However, the draft made no mention of reparations, and no representatives of the two communities were involved in its preparation. The protests led by the descendants of the victims stalled the signing and resulted in an ongoing lawsuit filed with the country’s High Court against the government. The charges allege the violation of a 2006 parliamentary resolution requiring that the descendants of the victims sit directly at the negotiating table with Berlin and that they—not the state—benefit from any compensation.

The country’s post-colonial legacy, much like South Africa’s after apartheid and neo-colonial systems more broadly, still sees the white minority owning most of the land: about 5% of the population, including the 1% who still speak German, hold 70% of agricultural property.

From the Herero and Nama perspective, Berlin should purchase the land from German-speaking owners and return it to the two communities to truly repair the colonial expropriations.

The government’s inaction on this issue and the boycott of the 2nd October date requested by the Herero and Nama demonstrate, according to Mazeingo, “Namibia’s collaboration with neo-colonial Germany.”

These commemorations aimed to draw public attention back to the failure of the negotiations and to push for implementation in line with the 2006 parliamentary resolution, because, as Mazeingo concluded: “Any organisation sponsored by entities outside of us is not ours, not for us, and we will not take part in it.”

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment