Peace or Profit? The Congo–Rwanda Agreement Under the Banner of Extractivism

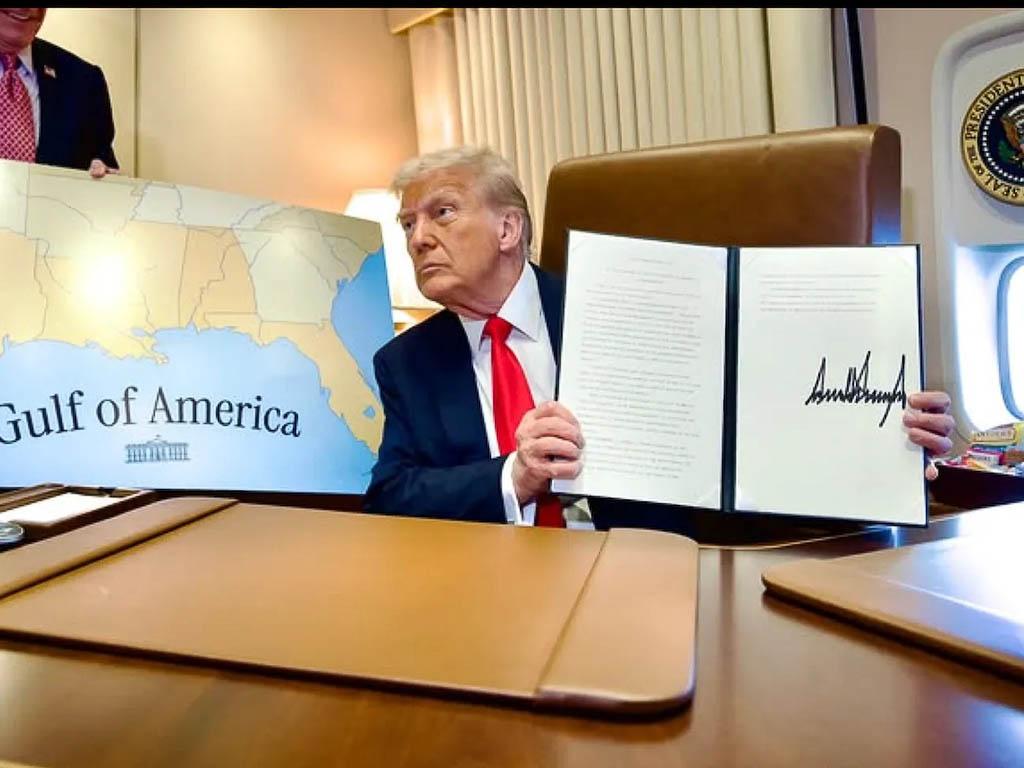

Confronti 01.08.2025 Luca Attanasio Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgThe agreement between Congo and Rwanda, signed in Washington and sponsored by Donald Trump, raises more doubts than hopes: behind the intention for peace lies a clear economic interest, especially for the United States. Criticism has been mounting, from Nobel laureate Denis Mukwege to Human Rights Watch, denouncing neo-colonialism and rewards to Rwanda despite its ongoing violations. In the background are millions of deaths and a very real risk: perpetuating exploitation rather than ending the war.

“We are obtaining, for the United States, many of the mining rights from Congo as part of the agreement.” These words, spoken by Donald Trump just minutes after the signing on June 27 in Washington D.C. of the agreement between the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and the Republic of Rwanda—supposedly intended to end decades of conflict and tension—certainly did not trigger the enthusiasm one might expect after a peace treaty. No one, to be clear, imagines that agreements ending war are the fruit of purely humanitarian impulses devoid of any self-interest. They are the result of compromises that inevitably leave all parties both satisfied and dissatisfied, and at their core lie profits. But for the main sponsor’s first words to be so blatantly focused on his own gains, with no reference whatsoever to the populations that have endured decades of war and mass slaughter, made many observers raise their eyebrows. Soon after, many began to suspect that the pact’s foundations were shaky. Criticism quickly followed, aimed at both the basis of the deal and its practical implications.

Benefits to the Strongest

The first and most obvious problem is that the deal seems to grant far more advantages to the strongest parties than to those in weaker positions. According to available information, the agreement will secure resources for the United States and, in some way, endorse Rwanda’s predatory policy toward the DRC. As Foreign Policy writes: “Instead of solving the problems created by Rwanda’s behaviour, the recent Washington agreement rewards it. The FDLR [Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda, the main Rwandan rebel group adhering to the Hutu Power doctrine] are mentioned over 40 times in the text, while the M23 [a rebel group active in eastern DRC, composed mainly of Congolese Tutsis] is mentioned only twice. This stark disparity suggests that the agreement will not address the root causes of the current crisis. More likely, it will strengthen Rwanda’s position at the expense of Congolese sovereignty and regional stability.”

Indeed, the pro-Rwandan M23 militias—responsible for repeated incursions and massacres in the Congolese provinces of North and South Kivu, and since January 2025 firmly in control of vast areas after taking Goma and Bukavu—are not only insufficiently mentioned, but also not explicitly condemned.

“Since the signing of the agreement on June 27, nothing has changed at all,” explains Father Giovanni Magnaguagno, a Xaverian missionary based in Bukavu. “The M23 is still in full control of the territories it captured at the start of the year, is expanding into neighbouring areas, and is sending in new troops. We all expected that sending General Dan Caine, dispatched by Donald Trump, would immediately change the situation, but nothing has happened.”

Four-star General Dan Caine, a senior officer of the U.S. Air Force, was sent to the region to oversee the operational mechanism for withdrawing Rwandan or pro-Rwandan forces from Congolese soil. It is still too early to judge his work, but Father Magnaguagno’s statement is reinforced by a report cited in the Belgian newspaper Le Soir, according to which the Rwandan president Paul Kagame is “aiming at the definitive annexation of eastern Congo,” in open contradiction with the commitments made at the end of June.

The Neo-Colonial Risk

Sharp criticism has also come from Dr. Denis Mukwege, Nobel Peace Prize laureate in 2018 for his work in treating and rehabilitating women victims of sexual violence: “Raw minerals will be sold off to Rwanda, which will process and export them, perpetuating a neo-colonial extractivist logic.”

The neo-colonial risk of this agreement is also clear to Lindani Zungu, founder of Voices of Mzansi, who, citing Ghanaian political thinker Kwame Nkrumah, wrote on Al Jazeera that the treaty “allows foreign powers to dominate not through direct occupation, but by economic means,” thereby perpetuating extractivism.

When considering the DRC—the most resource-rich country in the world, home to 70% of global cobalt (essential for electric car batteries) as well as abundant coltan, copper, and gold—and Rwanda, one must remember a key fact: the DRC, despite its immense mineral wealth, is among the poorest countries in the world, while Rwanda, without a single deposit on its territory, is among Africa’s most stable and prosperous nations, doing business with Europe and the U.S. in minerals and rare earths. Rwanda’s steady encroachment into eastern Congo has precisely aimed at controlling the mines, fuelling decades of bloody wars. According to the most reliable estimates, some 10 million Congolese have died in the various conflicts—a horrifying figure that amounts to genocide.

Unless action is taken on these factors—restoring a measure of justice, addressing the massive gap between possessed wealth and exploited wealth, and ending the ongoing dispossession of resources on behalf of third parties—it will be very difficult to achieve peace.

The Role of Congress

Of course, any agreement in which warring parties shake hands after years of bloodshed carries a certain aura of hope. If it brings even a brief respite to a battered civilian population, that is already a gain.

As Lewis Mudge, Central Africa director at Human Rights Watch, writes: “The United States Congress can help improve the chances of success and feasibility of the agreement by requiring that any investment in infrastructure or security support be conditional on the full withdrawal of Rwandan troops from the Democratic Republic of Congo and the end of Congolese support for groups responsible for abuses. Congress should also show support for investigations into serious crimes and ensure the establishment of international monitoring and compliance with the agreement.”

Whether the U.S. Congress—and especially the erratic figure who leads its government, more interested in his own wealth than in genuine efforts to restore peace and justice, and who recently considered sending asylum seekers who had reached the U.S. to Rwanda—will pursue this course remains to be seen. Regardless of the doubtful motivations behind the signing of the agreement, one can only hope that the two sides will be kept away from arms and that, alongside their own interests, the interests of the local population will be protected.

We have serious doubts, but at the same time, we cannot help but cling to this hope.

See, Pace o profitto? L’accordo Congo-Ruanda sotto il segno dell’estrattivismo

Photo. Cobalt mining in Congo ©The International Institute for Environment and Development, CC BY 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment