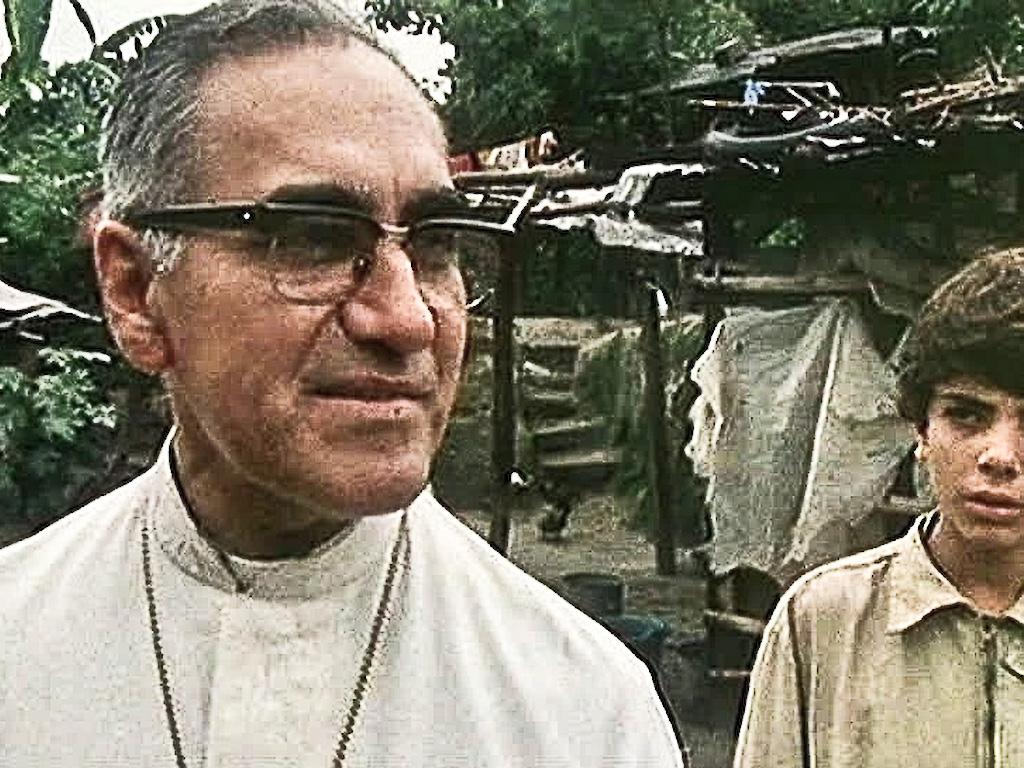

Monsignor Romero and Christian Hope

UCA 12.11.2025 Carlos Ayala Ramírez Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgThe signs of despair are everywhere: economic crisis, food crisis, ecological crisis, energy crisis, crisis of values, crisis in the family; even a crisis of hope (let us recall the “prophets” of the end of utopias). Each of these crises has something in common: they threaten, impoverish, or cut short life.

The need for hope

Erich Fromm, in his book The Revolution of Hope, tells us that hope is paradoxical: “it is neither a passive waiting nor a violent forcing of realities that will not occur. Neither weary reformism nor falsely radical adventurism are expressions of hope. To have hope means, instead, to be ready at every moment for what is not yet, without falling into despair if the birth does not take place within the span of our life.”

According to Fromm, people whose hope is strong see and foster all the signs of new life and are always prepared to help bring about what is ready to be born. According to the author, this is characteristic of the messianic vision of true prophets. They do not predict the future, but see present reality free from the myopias of public opinion and authority. They do not wish to be prophets; rather, they feel compelled to express the voice of their conscience, to say what possibilities they perceive and to show people the alternatives that exist. Monsignor Romero was undoubtedly one of these people: a cultivator of the signs of new life.

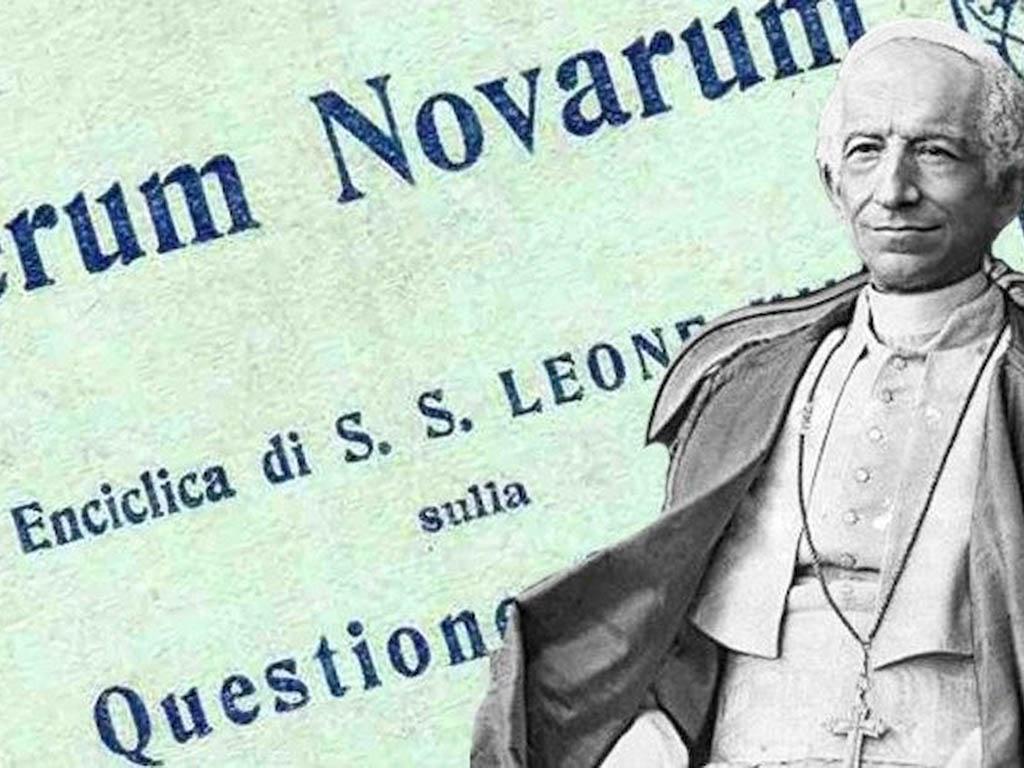

An essential characteristic of Monsignor Romero’s spirituality (cf. Martin Maier, Monsignor Romero, Master of Spirituality, pp. 148–149) is that he never lost hope, even in situations that appeared to have no solution. His attitude was not one of appeasement, under the slogan: “everything will eventually work out.” With Paul, he practiced “hope against all hope.” He placed his hope within the tradition of the prophets of Israel. They did not proclaim a cheap hope. The hope of the prophets was sustained by trust that God would lead the history of his people toward salvation, through all ruins, all disloyalties, and all catastrophes.

Hope from the prophetic vision of Monsignor Romero

For Romero, Christian hope is at one and the same time promise, task, and waiting (cf. Homily of 18th November 1979).

Promise: “The Christian people walk encouraged by a hope toward the Kingdom of God” (utopia).

Task: “Hope awakens the desire to collaborate with God, with the certainty that if I do my part, God will do his part and we will save the country” (praxis).

Waiting: “God’s hours must also be respected; one must wait when the Lord passes by in order to collaborate with him” (trust in God’s power).

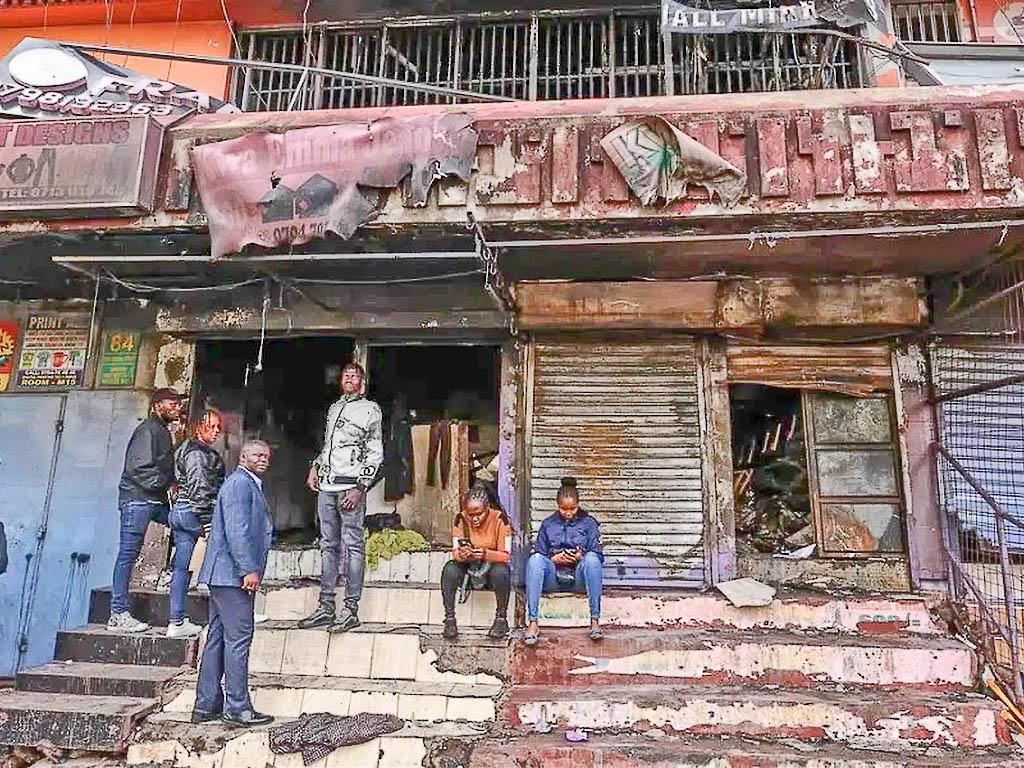

Two structural realities shaped the Salvadoran situation during Monsignor Romero’s ministry: social injustice (addressed in his 4th Pastoral Letter, 1979) and the repressive violence of the State (addressed in his 3rd Pastoral Letter, 1978). The principal victims of both realities were the poor.

Faced with this situation, which he described as a “frightful disorder,” Monsignor Romero defended the victims, and he did so by generating hope.

He generated hope by denouncing historical sin: “When the Church hears the cry of the oppressed, it cannot but denounce the social structures that cause and perpetuate the misery from which that cry arises” (2nd Pastoral Letter, August 1977).

He generated hope by responding with mercy to suffering: “Politics does not interest me. What matters to me is that the Pastor must be where suffering is; and I have come, as I have gone to all the places where there is pain and death, to bring a word of consolation to those who suffer” (Homily, 30/10/1977).

He generated hope by defending the poor and shedding light on processes of liberation: “The Church would betray its very love for God and its fidelity to the Gospel if it ceased to be the voice of the voiceless, the defender of the rights of the poor, the encourager of every just longing for liberation, the guide, promoter, and humanizer of every legitimate struggle to achieve a more just society” (4th Pastoral Letter, August 1979, no. 56).

A life inspired by hope

The content of hope also refers to a way of living. A life animated by love and justice is a source of hope.

Every act of love, conscience, and compassion is a source of hope. Every act of indifference, falsehood, and selfishness generates despair: “Let us not seek immediate solutions, let us not try to organize in one stroke a society that has been so unjustly organized for so long; rather, let us organize the conversion of hearts. Let them learn, one and all, to live the austerity of the desert, to savour the strong redemption of the cross; for there is no greater joy than earning one’s bread by the sweat of one’s brow, and there is also no more diabolical sin than taking bread away from the one who is hungry” (Homily, 24/02/1980).

An example of a life animated by love and justice is that of the Salvadoran martyrs. For this reason, Monsignor Romero considered them seeds of hope: “It is blood and pain that will water and fertilize new and ever more numerous seeds of Salvadorans who will become aware of the responsibility they have to build a more just and humane society, and which will bear fruit in the realization of the bold, urgent, and radical structural reforms that our homeland needs” (Homily, 27/01/1980).

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment