Water projects, respect for women. Sustainability in India's villages

Global Sisters Report 05.09.2019 Saji Thomas Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgUntil a decade ago, Hatu Devi could not even think of going to a grocery shop near her house. This resident of Jalimpura village of Banswara district (Northwestern Indian state of Rajasthan) had to depend on her husband or other male member in the family to meet her needs. Since her marriage at 13, she had to always cover her head and face with her pallu, the edge of a sari. She was not allowed to talk to men, even men in her family, except in an emergency.

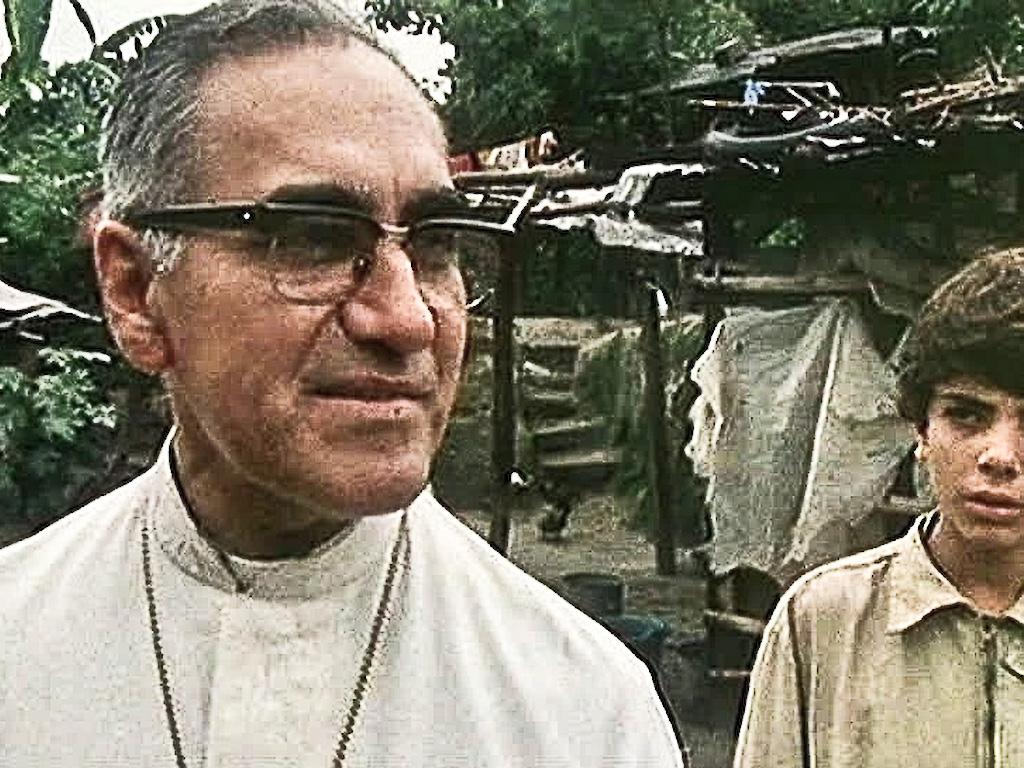

"Even then, I had to ensure that my face was not seen and head bowed, as face-to-face conversation was not the norm then. I no longer depend on my husband or others. I manage on my own now," says Devi, now 48. The world has become different today, thanks to a group of Catholic nuns.

The Hindu woman credits the Missionary Sisters, Servants of the Holy Spirit (SSpS), known as the Holy Spirit Sisters, for the "revolutionary transformation" in her life.

Hatu Devi is among hundreds of villagers who had life-changing experiences after the nuns started working among them in 2012. Through water projects, micro-loans, farming diversity and other means, the nuns not only checked migration of villagers to cities but also fought several social evils that subjugated women, such as child marriage. She is among 3,500 women and 4,000 men from 1,282 families in 8 villages in Banswara district who have found new meaning in their lives after the Holy Spirit nuns reached out to almost 10,000 people since their arrival. The nuns work under Udaipur Diocese.

Nearly 95% of the families belong to the indigenous Bhil community and are Muslim or Hindu.

The five nuns unofficially started their mission in Goeka Baria 15 years ago. Their biggest challenge was to retain the people in villages, as many used to migrate to Gujarat, an industrially developed neighboring state, where “they lived in unhygienic and subhuman conditions and could not send their children to schools," Sr. Jaisa Antony said. The migration peaked during the summer because of water scarcity. "Our study convinced us that poverty and distress migration would stop if we could find a solution to the water crisis and encourage people to cultivate their farms".

In collaboration with Germany's Kindernothilfe and Holistic Child Development India, the nuns initiated a project, Child Focused Community Development, which started in January 2011 and ended in March 2019. "Our main objective was to reduce migration, particularly of women and children, improve the coverage and quality of education, and find sustained livelihood," Antony said.

Many families started eating vegetables in 2012. Earlier, they depended mostly on forest leaves and seasonal produce to keep alive. Kamala Devi reported her family had survived on the income from cultivating their crops once per year on their tiny farm and occasional jobs of her husband. "Today, our life has changed so that our children are studying in schools and we have surplus income." She earns an average of 4,000 rupees ($58) monthly from tailoring while her husband works in his farm.

Before the nuns entered the village, women could not see even each other's faces. "We recognized each other with the help of our sari or legs, plus our voices. This worked only with close neighbors and family members," Kamala said with a smile. The nuns' intervention has freed the women from strict veil norms. They have not given up wearing veils, but they do not cover their faces: "Now we do our work in the house and outside without any interference from the male members."

Her husband, Kamalesh Garasiya 32-year-old farmer, said they never imagined "such a wonderful life" until the nuns arrived in 2012 and their work began to show fruit. "Now I have purchased a tractor with the farm income and the sisters' consistent support."

The nuns' emphasis on water conservation has helped improve the water table, ending the shortage of water for drinking and irrigation. "I cultivated only once in a year, as there was no water. Now I raise three crops in a year, as we have plenty of water," Garasiya said.

The sisters knew it was impossible to reduce migration without improving agriculture. "With the support of the villagers, we repaired and deepened 85 wells and dug five new ones that now supply water for drinking and irrigation in the targeted villages," Antony said. The nuns helped construct farm bunds and leveled lands that helped retain rainwater, improve the water table, and make soil more fertile."

However, the nuns had to face their share of opposition. "Some local leaders tried to oppose the nuns' work, saying it was a façade for religious conversion," Krishna Chandra, a retired government schoolteacher, says. The opponents included village council chiefs in some places. As people began to experience the benefit of the sisters' work, their opponents retreated.

"The sisters also networked with the government Krishi Vigyan Kendra [Agriculture Science Centre] of Banswara to ensure the farmers got the latest technology and knowhow," Chandra said.

The center tested seed variety to augment farm produce, such as maize, wheat, chickpea and rice, along with seasonal vegetables. Previously, most farmers had only grown wheat. The sisters encourage people to go for organic farming. Many houses in these villages have compost pits that have helped the farmers to minimize the use of chemical fertilizer.

The nuns brought together more than 900 women through 72 self-help groups and started income-generation programs such as tailoring, bamboo works, poultry farming and goat rearing, among others. The saving and credit activity through these groups helped the women avoid taking out loans from moneylenders. Hatu Devi said the loan she received from the self-help groups has helped her build a concrete house for her family. The sisters' activities have helped bring women out of "the four walls of their houses. Many women such as Hatu Devi are active in decision-making in their families and in the village," the nuns said.

Poji Devi, 65, spoke out about how happy she is that her daughters-in-law are enjoying the freedom denied to her when she was young: "Earlier, women were not respected. Things have begun to change. My daughters-in-law are no longer restricted to the kitchen or farmland."

The changes have also reduced the maternal mortality rate. "During our time, nobody was even taken to the hospital, even for a complicated delivery," Poji Devi said. The nuns opened a dispensary in their campus and taught the villagers to deliver babies in hospitals. With the help of the government's Integrated Child Development Services, the sisters also give nutrient-rich food to pregnant women and lactating mothers and the infants receive vaccines and nutritious food. "Once a month, health workers come to the village for immunizations. Nobody is afraid now. Earlier, even if government staff approached us, we never allowed any immunizations, as we were afraid that they might harm us," Poji Devi said.

The nuns' presence gave a major boost to the Udaipur Diocese’ education commitment. A primary school was opened in Goeka Baria in 1959. The nuns helped expand the school through the 10th grade in 2013. In 2018, they built a new wing with funds they solicited from Stichting Zijn, a Dutch welfare organization, to give more facilities to the students. Over the years, this work brought "immense changes among the villagers."

The one challenge the nuns have not been able to tackle is child marriage. "Child marriage is still prevalent, being so rooted as it is in the social fabric of society," Varkley told GSR. "Sometimes, we find our children missing from classes. It is only when they return we find their marriage was fixed."

Legal marriage for women is 18 and 21 for men in India. However, poor and illiterate people in many parts of Rajasthan and other states still follow the patriarchal tradition of child marriage.

"We need to create more awareness to end the practice. It will take quite some time. We have succeeded in ending distress migration and water crises and helped increase farm income and educate children," Varkley thinks. Their biggest achievement was women removing the veil that had kept them hidden and subjugated for so long. "They have now become independent and self-sufficient. What they need is further guidance that sisters will continue to give."

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment