When Power Replaces Law

El Heraldo de México 07.01.2026 Rodrigo Guerra López* Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgThe right to use force requires respect for the very foundations of law

There are moments in history when the decisive question is not who possesses the greatest strength, but whether an order still exists that is capable of containing it. When international law and the institutions entrusted with upholding it become weakened, power tends to take their place.

“International law” was born with figures such as Francisco de Vitoria, who conceived the community of nations as a moral and legal order directed towards the common good. When law ceases to orient power towards the good, it dissolves into violence. For this very reason, the world needs a reform of the United Nations, and in particular, a reform of its Security Council.

What does “reform” mean?

First: representativeness.

A body that decides upon global peace and security cannot indefinitely reflect the power map of 1945. Latin America, Africa and large regions of Asia rightly demand greater weight. Political legitimacy forms part of legal effectiveness: A Council perceived as an exclusive club loses moral authority and its capacity to mobilise.

Second: limits to the veto.

The veto was created to prevent a rupture between great powers; today, far too often, it functions as insurance for impunity. Mechanisms are needed to prevent a single actor from blocking collective action.

Third: automatic pathways out of paralysis.

If the Council fails to act, an institutional channel with broader universal legitimacy — for instance, the General Assembly — must be activated without delay, enabling coordinated and verifiable decisions rather than mere statements.

Fourth,

and the most difficult: credible coercive mechanisms under multilateral mandate, subject to strict oversight. Without the capacity for legitimate coercion, international law is reduced to exhortation.

Here, the Social Doctrine of the Church provides a compass: peace is not the absence of war but the fruit of justice; and the international community needs institutions that genuinely serve the common good. This requires realism: law without force is fragile. But it also requires morality: force without law is tyranny. The point of balance is an international authority limited by law, structured subsidiarily, oriented towards human dignity, and governed by clear rules. This is how Benedict XVI understood it (“Caritas in veritate”, no. 67).

At this moment, we face a stark alternative: either we strengthen an international order in which power remains subject to law, or we return to a scenario in which law becomes merely the decorative language of the victors. Renewing the UN does not automatically guarantee peace. But failing to renew it points towards a return of the law of the strongest as the habitual grammar of world politics.

Indeed, Pope Leo XIV is not unfamiliar with a perspective in which power is constrained. Looking directly at the case of Venezuela, he states: “The good of the beloved Venezuelan people must prevail over every other consideration and lead to overcoming violence and embarking upon paths of justice and peace, guaranteeing the sovereignty of the country, ensuring the Rule of Law enshrined in the Constitution, and respecting the human and civil rights of each and every person” (4 January 2025).

See: Ver, Cuando el poder sustituye al derecho

Secretary of the Pontifical Commission for Latin America*

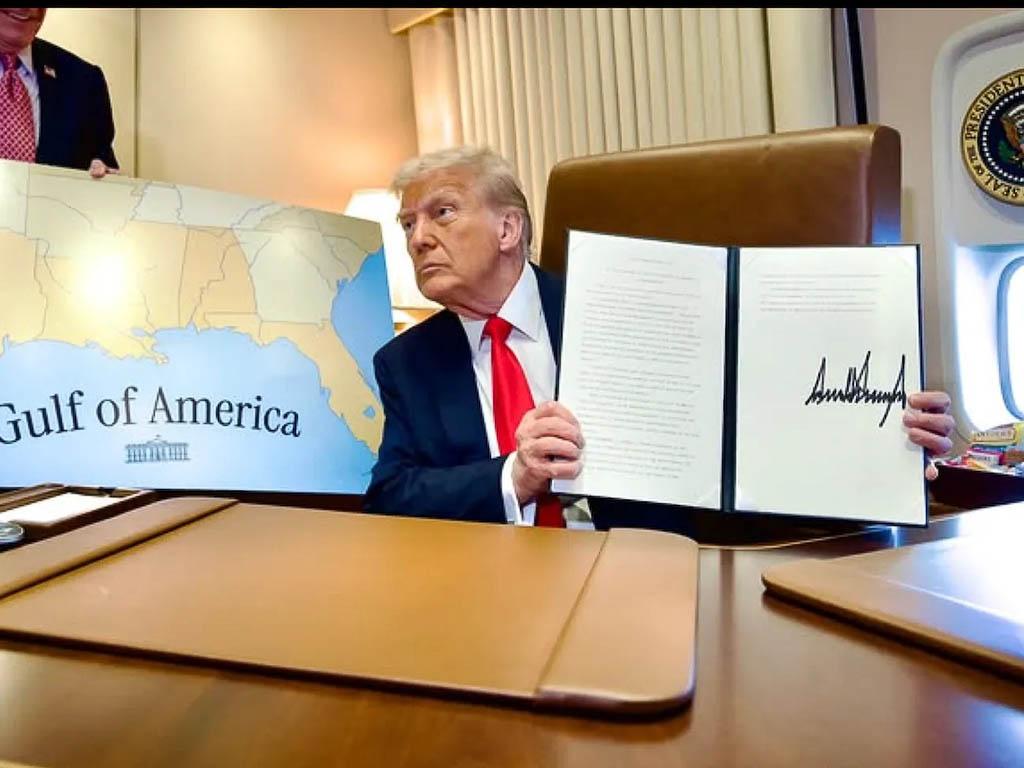

Photo: Marco Rubio and Donald Trump, October 2025 © Evan Vucci / AP Photo

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment